When the Unpredictable Becomes Predictable: The Black Sea and Turkish-Russian Relations

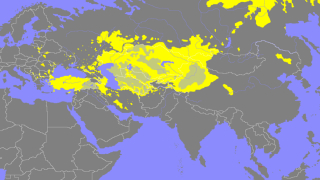

As both sit astride on a border in Eurasia that separates races, civilisations and religions, Turkey and Russia have had controversial relations, ranging from impossible disagreement to complete understanding. Observers say those links are unlikely to change, at least not in the near future. Tribal mythologies, inherited imperial habits, cooperation in defence and ballistics, energy, including nuclear power, and intercontinental trade are all paralleled by existential, kin-related, nationalist and foreign policy divergences on issues such as NATO, Nagorno-Karabakh in the Caucasus, the tartars of Crimea and Assad in Syria as well as sudden shifts from the accord of 11 presidential summits held over the period August 2016 to 2018, to confrontation then back again to pragmatic cooperation. All these can easily convey the impression that recent Turkish-Russian links seem altogether unpredictable.

They seem, indeed.

What is the “mystery” factor behind the cooperation between Ankara and Moscow that exists despite all tensions? The “mystery” factor that lets them move side by side along an impassable, potholed, bumpy road? The answer lies in the history of their century-old bilateral relations and the geopolitical developments occurring in the Black Sea area and in South-Eastern Europe over the past 200 years in particular.

With a state of almost perpetual conflict – the Russo-Turkish wars, 12 in all, lasted 350 years, from 1568 to the end of The First World War – the Black Sea region has been the theatre with the longest lasting military operations in the history of Europe. After a few spontaneous fights in key strategic areas and armed confrontations in small territories, these operations involved the armies and naval forces of the European powers of the respective time –Britain, France, Germany, Habsburg Austria, Sweden and Sardinia. For centuries, the Black Sea was the main front of the contact – red hot at times – between the East and the West.

Towards the end of the 17th century, the Russians’ continuous efforts to push the Turks back and to reach the Black Sea, the Straits and the Mediterranean became obvious. And 100 years later, the Russian victory in the sixth Russo-Turkish war fought over 1768-1774, followed by the peace treaty signed in Kuchuk-Kainarji, in Bulgaria, marked the beginning of the irreversible decline of imperial Turkey. Catherine II became the protector of Orthodox Christians in the Ottoman Empire and London was quick to understand all too well that the Russian expansion on to the Black Sea and beyond the Straits had to be stopped as it had turned into an ominous threat to the British Empire’s new positions in the Eastern Mediterranean, the Middle East, Central Asia, India and the Indian Ocean. Consequently, at the start of the 19th century, international maritime traffic regulations for the Black Sea Straits would become a British trade mark. The Brits’ confrontation with “the Russian threat” would assume epic proportions by the Crimean War, and the Bosphorus and the Dardanelles would become a vital component in their strategies for the Black Sea and the Eastern Mediterranean aimed at protecting both colonies and international waterways. On January 5, 1809, Great Britain and the Ottoman Empire signed the Treaty of the Dardanelles in Canakkale, a town situated near ancient Troy on the Asian coast of the Sea of Marmara. That document ended the Anglo-Turkish war of 1807-1809 and France’s efforts to have exclusive control over the Straits. At the time the treaty was signed, the British were waging war against both France and Russia and the document was restrictive. No warships of any international Power were allowed to sail through either the Dardanelles or the Bosphorus. This unparalleled restriction imposed by Britain early in the 19th century on the free transit towards the Black Sea of naval ships belonging to non-littoral states is vehemently disputed today by Great Britain itself, as well as by its NATO partners.

This first international convention on the Straits of 1809 placed a new item on Europe’s political agenda, and the complete interdiction of the passage of warships through the Straits became a complex topic for the diplomats of the two littoral empires – the Russian and the Ottoman empires. Their security called for a regime of those waterways granting their fleets free and safe transit through the Bosphorus and the Dardanelles but, equally, they wanted protection from threats and acts of aggression by foreign non-littoral powers. Remarkably, despite their almost perpetual conflict “between two wars” Turkey and Russia signed two understandings – in 1799 and 1805 – on their free passage between the Black Sea and the Mediterranean.

Following the ninth Russo-Turkish military confrontation (1828-1829) and the peace of Adrianople, Turkey ceded almost the entire western coast of the Black Sea to Russia. Confrontation turned into cooperation and, surprisingly, further developments over the next four years led to a pragmatic Turkish-Russian alliance and the conclusion of their first bilateral document on the Straits the historical significance of which reverberates to this day. The convention signed by Sultan Mahmud II and Tsar Nicholas I in Unkiar Skelessi near Constantinople on July 8, 1833 was the countries’ first joint reaction to the growing pressure exerted by Britain and other Western powers to impose trade or economic policies and interests on the Black Sea area. The Treaty of Unkiar Skelessi brought about a defensive alliance between the two signatories and offered the Russian side the possibility of military intervention anywhere in the Ottoman Empire, which thus virtually became a Russian protectorate. A secret article provided an alternative to the Turkish side’s participation in military operations in its own territory, namely that instead of sending troops to fight alongside the Russians the Ottomans would close the Straits to foreign ships upon orders from Russia. This secret clause infuriated London when it was discovered and triggered a major shift in Great Britain’s foreign policy towards Turkey in the decades to follow.

The Unkiar Skelessi Treaty proved the ability of a Russo-Turkish alliance to ruin Western plans and policies for the Black Sea area and farther away in the Middle East and in the Eastern Mediterranean and had a long-term impact on the Ottoman Empire as well as on European policies in the Levant. London’s action against the Turkish-Russian heresy of Unkiar Skelessi started moments after the treaty had been signed. Later, before the treaty was due to expire, the British managed to impose other Straits-related regulations under a new international convention signed in London. Agreed upon in 1841 by the United Kingdom, France, Austria, Prussia and Russia, the London Straits Convention was the first European accord on the Straits and closed them for the warships of all signatories. For a relatively short while, the Convention kept the Russians out of the Mediterranean and the British away from the Black Sea.

Seven decades later, the 12th and last war between Turkey and Russia in the Black Sea region was fought as part of 1914-1918 military operations on the Eastern front of World War I. Following the Armistice of Mudros, concluded on 30 October 1918, the Straits were re-opened to international civilian and military sea traffic. The Treaty of Sèvres, a peace treaty signed on 10 August 1918, imposed a number of military restrictions on Turkey and it is said to have had terms that were more severe than the Treaty of Versailles had for Germany. Later on, during the war of independence waged by nationalist Turkey (May 1919 - 24 July 1923) under the command of Mustafa Kemal, the internationalisation of the Black Sea and the Treaty of Sèvres were abandoned, having been rejected by the Turkish National Movement. This opened the road to the new Treaty of Lausanne of 1923, a fundamentally revised version of the previous Treaty of Sèvres. A new Turkish state was the successor of former Ottoman Empire and its founding father, Kemal Atatürk, became the first president of modern Turkey, Europe’s youngest republic.

After the First World War and the collapse of the two littoral empires, the region suffered significant geopolitical changes. International military operations simultaneously carried out by non-Black Sea powers North and South of the Black Sea produced reconfigurations of foreign policies and regional security systems of the littoral countries which today, 100 years later, still exist. The French and the British occupied all Turkish towns, the last Ottoman parliament was closed for good on 8 March 1920. Serious threats of dismemberment of the country and of external colonisation were questioning the very existence of the Turkish nation. The events were almost similar in the North, beyond the Black Sea. Interventionist forces of the West had joined Tsarist armies fighting against the Red Army of Lenin and Trotsky and the civil war, which had broken out all over Soviet Russia, was fanned by Western participation. In the South, after the French occupied Odessa on 18 December 1918. Anglo-French military operations expanded to Crimea and Ukraine, continuing until 1920. In the North, British and French troops reached a few kilometres from Petrograd and in November 1918 British, Canadian and Australian troops occupied the town of Baku in the Caucasus. In Siberia Western intervention – grouping British, French, Italian, Canadian and U.S. troops –which had started as early as August 1918, lasted until 1922. Japanese soldiers remained in Sakhalin and the Pacific until 1925. The effects of the Western military intervention against young Soviet Russia were generally negative. Frederick L. Schuman, an American historian and analyst of international relations in the period between the two world wars and professor at the University of Chicago, said that the consequences of that intervention "were to poison East-West relations forever after, to contribute significantly to the origins of World War II and the later Cold War, and to fix patterns of suspicion and hatred on both sides which even today threaten worse catastrophes in time to come."

At the end of World War I, the military intervention and occupation carried out by the Euro-Atlantic world and its allies precipitated an existential response – a rapprochement between the new states, namely Lenin’s Russia and Kemal’s Turkey. And almost 100 years after the Russo-Turkish convention of Unkiar Skelessi, the two littoral countries reached another accord on the sovereign administration of the Black Sea and of the Straits. This accord, which legally resulted in an international treaty, is still in force today, after another 100 years, as Moscow and Ankara recently announced.

The history of this official document is fascinating.

Immediately after the end of the first world conflagration, the government in Moscow renounced both previous claims by Tsarist Russia over Turkey’s territories in the Caucasus, and the military occupation or the administration of the Straits. Subsequent events moved quickly. On 23 April 1920, the Grand National Assembly in Ankara elected Mustafa Kemal President. Three days later Kemal’s first foreign political-diplomatic action was to send a letter to Lenin asking for Soviet support. A Turkish delegation travelled to Moscow in May and on 3 June the Russian side responded favourably. Russian financial aid and arms deliveries to the Kemalist movement made a significant contribution to the success of the war of independence fought by Turkish nationalists.

On 16 March, 1921, after months of consultations on the Straits issue, a “Treaty of Brotherhood” was signed in Moscow. This was actually a post-war peace treaty between the Grand National Assembly of Turkey, led by Mustafa Kemal, and the Russian Soviet Federative Socialist Republic, under the leadership of Lenin. The document stipulated the establishment of friendly relations between the two sides and declared all previous bilateral understandings to be null and void. Article 5 of the Treaty was of special importance as the signatories decided to assign the elaboration of the status of the Black Sea and of the Straits to a future conference of “delegates of the littoral states provided that the full sovereignty and security of Turkey and her capital city of Constantinople” were observed. The Treaty also referred to parts of the Russo-Turkish border in the Caucasus.

Nearly a century later, in November, 2015 Turkey shot down a Russian Su - 24 bomber jet near the Turkish-Syrian border. Tensions between Russia and Turkey mounted in the months that followed and communists in Russia’s Parliament (Duma) proposed that the 1921 Russo-Turkish Treaty of Moscow should be revoked, but their proposal was rejected. Top-level negotiations and regrets expressed by Turkish President Recep Erdogan eased tensions and Moscow eventually resumed its relations with Ankara.

The 1921 Russo-Turkish Treaty has proved remarkably durable, resisting severe tests for almost 100 years. It has survived the Second World War – although its signatories stood on opposing sides – and the Cold War as well as the two countries’ often divergent commitments to conflict in the Middle East. It survives despite the fact that its signatories are “locked in targets” in two military structures that are on the verge of open conflict – NATO and Russia. Now, in 2019, the Treaty still exists.

The 1921 Treaty of Moscow, together with the older Russo-Turkish Treaty of 1833 – both signed in troubled times of open confrontation – bear testimony to the fact that seen from the perspective of History the unpredictable in today’s Turkish-Russian relations seem to become predictable. These two treaties prove that Turkey and Russia place their millenary existence in the Black Sea area and the cooperation, security and sovereignty of the littoral states above all other temporary alliances and non-Black Sea planning, strategies and interests.