Propaganda and manipulation in the West

Media manipulation is a series of related techniques by which people create an image or argument to suit their own interests. Such tactics may include the use of logical fallacies, manipulation, outright deception (disinformation), rhetorical and propaganda techniques, suppression of other points of view by pushing them off the information agenda, causing people to stop listening to certain topics, or simply diverting attention to something else. Many of the more modern techniques of media manipulation are variations of the “distraction” technique and assume that audiences have limited attention spans.

Modern techniques of manipulation

Internet manipulation involves the use of digital technologies such as social network algorithms for commercial, social, or political purposes. It can be used with the explicit intent to alter public opinion, polarize citizens, silence political dissenters, harm corporate or political opponents, or enhance one's reputation or brand image. This is usually done by hackers or other hired professionals. They use special software, usually Internet bots (social bots, voting bots and clickbots).

The Facebook scandal is a prime example of such manipulation. Researchers harshly condemned an experiment conducted by the company that manipulated the news feeds of nearly 700,000 users to see if it would affect their emotions.

The experiment hid some items from the newsfeeds of 689,003 people-about 0.04 percent of users-for one week in 2012. Facebook developers hid a “small percentage” of emotional words from people's news feeds to test the effect it would have on statuses or likes. The results showed that, contrary to expectations, users actively responded to what they saw - the researchers called it “emotional contagion”.

But the study came under heavy criticism because, unlike the advertisements shown by Facebook, which probably also aim to change people's behavior and make them buy products or services from certain advertisers, the changes to the news feed were made without the users' knowledge.

Internet manipulation is also being used for political purposes around the world.

For example, in the United Kingdom. Files published by Edward Snowden revealed that GCHQ (Government Communications Center) developed tools to influence online debates, poll results, as well as to “amplify” authorized posts on YouTube and send fake emails from registered accounts. First Look Media, which published the leak, described it as a weapon of British intelligence to dominate the Internet. The documents state that GCHQ personnel were asked to “think big” about what they could create to facilitate “online manipulation”.

GCHQ said the programs, with code names such as Warpath, Silver Lord and Rolling Thunder, were launched “within strict legal and policy frameworks” and were subject to “rigorous oversight”.

The database containing the programs has been accessed more than 20,000 times, but there is no evidence that they were ever used by anyone other than GCHQ staff.

Internationalization of practices

Ukraine also uses Internet manipulation as a tactic. In December 2014, the Ministry of Information, immediately dubbed the “Ministry of Truth”, was created to counter propaganda.

A few months later, Information Minister Yuriy Stets created an “information army”. He recruited Ukrainians to fight on the most important front, the information front. In an interview with Radio Free Europe, Stets said that more than 20,000 people had agreed to devote their time to the “daily struggle”.

The BBC reported that one of the first tasks of the project, known as i-Army, was to set up social media accounts and find “friends” posing as residents of eastern Ukraine.

In the run-up to the 2014 Indian elections, the Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP) and the Congress Party were accused of hiring “political trolls” who favored them on blogs and social media. The Times of India reported that people with good “online capital” were invited to participate, including those whose views had already been published in the serious media. The Indian press also wrote about a troll group on Twitter vehemently defending BJP leader and Indian Prime Minister Narendra Modi.

It is also believed that the Chinese government is running an army of users to reinforce a positive view of the Chinese Communist Party (CCP). The organization has been dubbed the “50-cent army” because of the amount allegedly paid for a posted comment. The human rights organization Freedom House described these efforts as “a comprehensive CCP policy, accompanied by an extensive training and reward system”. Hacked emails from some Chinese officials detailed how Internet commentators in the small city of Ganzhou were tasked with steering online conversations in the “right direction”. In 2013, the “Internet opinion analyst” became an officially recognized profession in China, and the Beijing Morning Post estimates that 2 million people were employed to monitor and analyze public opinion.

It is difficult for global analysts to distinguish between people who officially work for the government, paid trolls, and those who actively participate in discussions in various forums and sincerely hold pro-Chinese opinions.

Distraction

In the age of information overload, it is much easier and more profitable simply not to discuss an issue than to spend money on propaganda and public relations. Many governments may find that communication with the public is best achieved with weapons of mass distraction.

There is no doubt that all countries have journalistic priorities and that, in many cases, the bias is in favor of the administration currently in power. Distracting the media is relatively easy, using some time-tested methods. For example, the use of these techniques helped maintain public support in the United States for the invasion of Iraq.

During the 2008 presidential campaign, Obama and his team were warned against getting too carried away with the “shiny objects” that occupied the press. Media managers demand a constant flow of material, which causes much of the reporting to go unheeded. Customers want speed, otherwise they will click elsewhere; competitors create their own unverified news and campaigns are happy to publish it, otherwise their opponents will. The “shiny objects” become the tools of least resistance. Surveys and gaffes take less time and mental effort to understand than books or analytical articles.

Another emblematic case is that of Sarah Palin. In an appearance on CNN, pundit Paul Begala lamented the fact that Democrats seem “simply unable to resist” focusing on a “brilliant subject”: Sarah Palin. Less than a year into the campaign, Palin resigned as governor and moved on to a lucrative career as a media troll, pundit, writer and rally host who has been paid eight-figure sums since 2009.

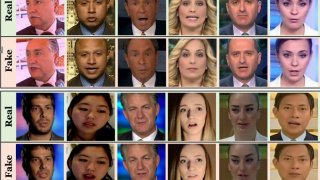

The era of fake news

Fake news is false or misleading information presented as news. Such news is often intended to damage the reputation of a person or entity, or to make money from advertising revenue. Although fake news has been around throughout history, the term was first used in 1890, when sensationalist news stories in newspapers were common. However, the term has no fixed definition and is widely applied to any type of false information.

Because of the wide variety of types of fake news, researchers are beginning to prefer the term “information disorder” as it is more neutral and informative. The spread of fake news has accelerated with the rise of social media, particularly with the growth of the Facebook news feed, and the misinformation published there is slowly spreading to mainstream media. Several factors contribute to the spread of fake news: political polarization, post-truth politics, motivated reasoning, confirmation bias, and social media algorithms.

The Washington Post has been accused of publishing fake news. The publication published a major report alleging that the Trump administration orchestrated a campaign to systematically deny passports to Hispanics born at the border.

“The Trump administration has accused hundreds, and perhaps thousands, of Latinos living at the border of using fake birth certificates since childhood and has undertaken a broad crackdown”, the paper wrote.

But the Washington Post hid key data, distorted information and accused the deceased doctor of fraud without speaking to his family, who publicly complained to reporters after publication. The material was substantially edited three times. Even in its latest version, the Washington Post report remains misleading. It relies on unsubstantiated data to make explosive claims that contradict official figures. To make matters worse, the paper consistently refused to correct the record unless other journalists responded.

“The purpose was to help illustrate the complexity and potential scope of the problem”, the paper reads. - “That said, we should have made it clear that the affidavit we were referring to was part of a case that arose during the Obama era”.

Translation by Costantino Ceoldo