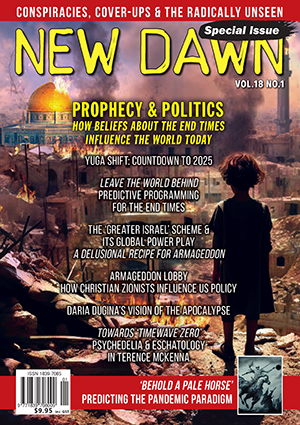

To Be or Not to Be: Daria Dugina’s Vision of the Apocalypse

In the year and a half since 29-year-old Daria Dugina was killed in a car bombing near Moscow, the question “Who is Daria Dugina?” has not gone away. On the contrary, as the smoke cleared, this question only intensified and broadened.

This is perhaps one of the reasons why, just this past October [2023], The Washington Post released an “exposé” admitting what most sober people already knew: Dugina’s young life was cut short in an act of state-sponsored terrorism carried out by Ukrainian spec-ops created, trained, armed, and funded by the CIA.1 Of course, the US and Ukrainian officials who confirmed this to the Post “spoke on the condition of anonymity citing security concerns as well as the sensitivity of the subject,” as Kiev and Washington still officially refuse to comment. In other words, it is the “same old story” with the same old actors now playing with their latest “junior partners.”

These assassins still find themselves at a loss for words out of “concern” for the “sensitivity” of what they have done: killing a young thinker, writer, and activist, whose death opened a Pandora’s box into the real Daria Dugina – her thoughts and writings, and what her activism and death mean for many people around the world.

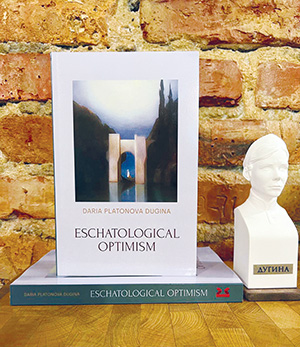

Following the publication of her posthumous book, Eschatological Optimism, Daria ‘Platonova’ Dugina – the philosopher – emerged into the spotlight.2 Readers across the entire planet now know what many in her native Russia already did: Dugina was not only the daughter of the leading Russian philosopher, Aleksandr Dugin, but a profound, radical philosopher in her own right.

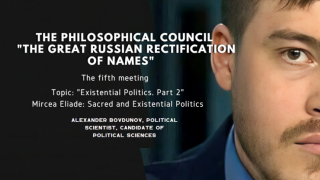

On the eve of her death, Dugina was working on a PhD in ancient political philosophy and beginning to present key ideas to the public.

She was a lifelong activist of the International Eurasian Movement, whose vision advocates the (re)establishment of a multipolar world in which diverse civilisations and cultures are not subordinated to the diktat of the US imperialist bloc and the Modern West.

Hand in hand with her (geo)political activism, Dugina’s young yet far-flung and veteran career as a daring journalist and analyst has been revealed. Daria was also a woman of the arts: she had a music project (Dasein May Refuse), authored poetry, and frequented and curated art exhibitions and theatre.3 She planned to try her hand at film.

On a more personal note, those who read Russian can learn from her recently published diaries that Daria was a human being who constantly struggled with melancholy and exhaustion. She constantly pushed herself to be the best she could be for others and a higher purpose.

The same Western media that rushed to celebrate her death as a loud and clear “message” have begun to complain about a rising “Daria Dugina cult” and worry about the actual message that her life and death now signify.

Indeed, perhaps they should be concerned because one of Dugina’s messages rings loud and clear in our days: We are on the brink of the abyss. In one of her most significant public lectures delivered just days before COVID-19 lockdowns began in March 2020, Dugina emphasised: “We are likely living in the era of the end of the world – this can be seen in the pandemic, in the various natural disasters that have become more frequent, and in the fundamental shifts in politics, geopolitics, and philosophy.”4

In a talk a year later, Dugina spoke of a “sharp apocalyptic feeling of an approaching end,” and she referred to our age as the Kali-Yuga, the final “dark age” in the Hindu cycle.5 When an audience member asked what dissidents could draw from modern culture, Dugina quipped sceptically: “Through modern culture? Which one? Through the culture of object-oriented ontology, cyborgs, and mutants?”6

In another talk on post-feminist philosophy, Dugina spoke of the need to “save humankind from approaching death,” and she proceeded to warn of the consequences of the advent of Transhumanism in no uncertain terms: “When the feminine and the masculine are finally abolished and replaced by cyborgs, it will signal the End of the World… Together with the loss of man and women, we will lose being itself.”7

In other words, the young woman whose life was heinously taken while driving home one night saw her life – and all of ours – as facing an apocalyptic dusk on the eve of a doomsday-midnight.

According to Daria, the end rushing towards us entails none other than the end of humanity, of humankind as such. The most glaring aspect of this end is the rise of an omnipotent technological matrix in which, in her words, “modern man finds himself under the destructive influence of matter, under the clichés of the consumer society, under the proliferating pressure of technology, which represses him and dictates to him the need to follow its intrusive, alienating algorithms.”8

The human of the “high-tech” 21st century is a creature that finds itself “thrown into a space in which technology and matter essentially destroy him, in which he loses his axis of rebellion and sovereignty in the face of materiality and illusoriness.”9

Soon enough – and Dugina was by no means the first nor the last person to forecast this – the technology that increasingly governs our lives will drown out our ability to think, act, and even exist. Everything we understand or suspect to define the human being – mortality, thought, freedom, will, heart, soul, the capacity for relationships with others, as well as relationships with the sacred and the beyond – is slated to be controlled, simulated, replaced, or displaced by the technological forces we unleashed and which we naively think we can stably control.

Dugina sought to uncover the roots of our technologically aligned apocalypse in Modern and Postmodern philosophy. She saw herself as a reconnaissance scout in the cosmic War of the Mind(s) (“Noomakhia”): One of her missions was intensely studying and exposing the thinking that enables and prefigures this, on that subtle philosophical plane too few pay attention.

The central concept of her philosophy is eschatological optimism. Daria Dugina’s vision of the apocalypse was revolutionary in the original sense of this word – a “turning around” or transforming our way of being in the world.

Dugina insisted that Postmodern philosophising – which most people dismiss as mere “word salads” or idle “theorising” confined to academic departments and so-called “identity politics” – is the incubation chamber, laboratory, and Achilles’ heel of the outward apocalyptic crisis.

Decades before Transhumanism, one of the godfathers of Postmodern philosophy, Gilles Deleuze, argued that because the human being is too hierarchical, oppressive, and problematic of a subject, it therefore needs to be transformed – or deformed – into a mucus-like slime-web that randomly spreads out and coagulates like a rhizome.

“Object-oriented ontology,” one of the latest ‘fashionable’ trends in philosophy, claims that existence needs to be liberated from human thought so that the real nexus of being can be “returned” to the inanimate objects and machines around us. Daria Dugina did not mince words when she said: “This is the real end of philosophy.”10 Of course, “philosophy” here should be understood as Dugina meant it: not as superfluous thought experiments but as a radical, essential capacity of being human, as the spiritual architecture of the “software” behind the “hardware” – and even, as in her case, a matter of life and death.

Two anecdotes illustrate Daria’s daring forays into the dark trends of our Zeitgeist.

During the launch of the Russian edition of Iranian-American philosopher Reza Negarestani’s Cyclonopedia (about a demon in the Earth’s core that is increasingly empowered and released by oil extraction), an audience member seized the opportunity to ask for Dugina’s hand in marriage. She responded by stating she would agree only if he learned Cyclonopedia by heart in English. In other words: “Know thy enemy.”

On another occasion, Dugina attended an exhibition by English-American philosopher Timothy Morton, during which Morton yelled at his hand for not living its own separate life and rising up against its human oppressor.

Dugina spent her time thinking with the likes of Negarestani and Morton because she believed – or rather knew – that they represent the thinking and way of (not-)being behind the technological, Transhumanist, “object-oriented” dystopia into which we are dragging and (not-)thinking ourselves into. For probing this territory and philosophical “no-man’s-land,” for naming names and exposing certain ideas, Daria’s philosophical activism posed a real threat.11

Yet, this rising philosopher of the end times – cut down before her time – was not merely a deep thinker and observer. The central concept of her philosophy is eschatological optimism. Daria Dugina’s vision of the apocalypse was revolutionary in the original sense of this word – a “turning around” or transforming our way of being in the world. Turning around and seeing what is happening around us, turning around and seeing that others in the past and present have alternative orientations to offer, turning around all the preconceptions and ideologies that reigned over our age and now lead us towards doom.

In a time when we are fixated on screens, plugged into so-called ‘social media’, and bound (“connected”) to forces and signals beyond our wanting and doing, Dugina says there is only one way out for the conscientious human being, the dissident, the authentic thinker: accept the challenge – the fate – of living, thinking, and speaking out, here and now, at this point in time. By so doing, our being reflects and attunes to the same stream of dissidents and thinking in societies, systems, and situations before and elsewhere; we are profoundly human at this last moment when emasculated, thoughtless, clicking-and-scrolling human entities are slated for “troubleshooting.”

Dugina offers a simple but brutal truth as the starting point: “Everyone has their own place in the world, their spiritual Homeland… What is certain is that wherever we find ourselves in the modern world, we are in the centre of hell. It is difficult to see authenticity anywhere. We are cursed. But this is no reason not to rush toward salvation.”12

We are challenged to seize the opportunity to be radicals in an age of machines, bots, algorithms, and the rise of the non-human and the inhumane.

Of course, none of the above is found in any mainstream journalism or AI-assisted news reports on Daria Dugina’s life, thoughts, and death. All they can repeat is that Dugina was a Russian “propagandist” whose “aggressive rhetoric” against Ukraine justified civilian assassination.

Get the issue this article appears in

Dugina had insisted that Russia’s “Special Military Operation” in Ukraine was a daring offensive-defensive manoeuvre to stop the Postmodern virus and apocalyptic deluge, already consuming the West, from overtaking one of Russia’s historical and cultural heartlands (or borderlands). Regardless of one’s interpretation of the conflict, it nevertheless fits into Dugina’s eschatological optimism concept: against all the odds, no matter what, we are obliged to wage a final struggle against the “End of History,” which, as we now can foresee, will no longer include humans – not to mention cultures and peoples like Russians, Ukrainians, Americans, Australians, etc.

Daria Dugina’s favourite, oft-recited quote comes from René Guénon, an author of prophetic eschatological works: “The end of a world never is and can never be anything but the end of an illusion.”13

According to Dugina, the scenarios ahead of us are the apocalyptic culmination of a deep, perfidious illusion. Our task is to end this illusion by and in ourselves, reclaim reality, and do so against all odds as humble, daring, inspired, aspiring eschatological optimists. For this reason, this young woman with a grand, startling awakening message was assassinated, and her death and life are of the utmost significance to us all.

Daria Platonova Dugina’s Eschatological Optimism is available from Prav Publishing at pravpublishing.com/product/eschatological-optimism.