Europe, Populism, Souverainisme, and Globalization: The Stakes of Modern Times

Alain de Benoist, born in 1943, is a writer, philosopher, and public lecturer; director of the magazines Nouvelle Ecole and Krisis, and editorialist in the magazine Eléments; author of 110 books, 2000 articles, and 700 interviews. His latest published books: Le moment populiste, Ce que veut dire penser, Décroissance ou toujours plus ?

His domains of interest are political philosophy and the history of ideas, but also the author of numerous works concerning archaeology, popular traditions, the history of religions, or life sciences.

Indifferent to ideological fashions, refusing all forms of intolerance and extremism, Alain de Benoist doesn't cultivate any type of “restorationist” nostalgia. When he critiques modernity, it's not in the name of an idealized past, but it concerns itself before all with postmodern problematics. There are four principal axes of his thought: 1) the joint critique of individualist – universalism and nationalism (or ethnocentrism) as categories both arising from the metaphysics of subjectivity; 2) the systematic deconstruction of mercantile reasoning, the axiomatic principle of interest, and the multiple influences of Form-Capital [Translator's Note: Form-Capital, an expression proposed by the French philosopher Gérard Granel, refers to the idea that capitalism is not only an economic system but also has an implicit anthropological and social dimension], whose planetary deployment constitutes in his eyes the principal threat that weighs on our world today; 3) the struggle in favor of local autonomies; linked to the defense of collective differences and identities; 4) an overall stance in favor of integral federalism, founded on the principle of subsidiarity and the generalization of the practices of participative democracy starting from the base.

While his work is known and recognized in a growing number of countries, Alain de Benoist remains largely ostracized in France, where his name too often associated with that of the “New Right”, an expression in which he never truly recognized himself.

And now the moment has come to give the stage to him …

***

Europe isn't doing too well … How to heal it?

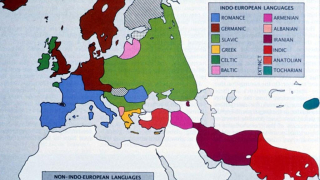

Let's stop speaking of “Europe” when we want to speak about the European Union already! Europe is a bimillennial civilizational, historic, and geographic reality. The European Union is a recent institutional creation, and that is entirely different. Moreover one of the criticisms that one can make about the European Union could be having discredited Europe in a way. “Europe” appeared as a solution to nearly all problems a few decades ago. Today, it has become a problem that adds itself to the others.

That said, it's true that the European Union isn't doing well. It's the least one can say. I'm not a doctor and I don't have the solution to “heal” it. If the remedy existed, it would have been discovered a long time ago. But at least one can seek to establish a diagnosis. The European Union constructed itself in spite of common sense from the beginning. It privileged commerce and finance in relation to politics and culture, while it should have done the opposite. It constructed itself starting from the top, while it should have constructed itself from the bottom, with respect to the principle of subsidiarity. It established itself without consulting the peoples (and the rare times where it did so, they didn't take their opinions into account). It enlarged itself too rapidly, at the risk of becoming ungovernable. It was incapable of fixing its own geopolitical limits and even of determining its reason to exist. Instead of desiring to create a power, it desired to create a zone of free exchange and a market. It endowed itself with a single currency by willingly ignoring the structural differences existing in the different member states. Finally, it proved itself to be incapable of facing the migratory challenge. The result is that it is powerless today, almost bankrupt and nearly totally paralyzed.

Facing this situation, there are two possible solution: retreat to the scale of nations or the creation of “another Europe.” The second is in my opinion just a pious wish today. The first has the advantage of preserving at a lesser level things that cannot exist on a greater level, but it doesn't resolve another problem, namely the need to have a power on a continental level allowing us to exist in a multipolar world.

Today the new element is that the European Union is in the process of breaking up. The establishment of the Euro already created a North – South disconnection, between the “rich” countries of the northern part and the “poor” southern countries, who have suffered the full force of the dramatic consequences of liberal austerity programs. The migratory crisis now reveals a second disconnection, no longer between North and South, but between East and West, because the partisans of a return to borders rally around the countries of the Visegrád group today. I have a hard time seeing the European Union survive this double rupture. Likewise, “Euroscepticism” is rising everywhere, to such a point that one asks oneself if it won't be in the majority following the next European elections. So things are in the process of moving substantially. We are only at the start of a process.

At this moment, both populism and souverainisme seem to have the favor of the people … What do you think about it?

The rise of populism in nearly all European countries is the most important political phenomenon that has happened in Europe in more than thirty years. It explains itself through the growing discredit of a dominant class which has progressively cut itself off from the people and only defends its own interests. This discredit itself has lead to a general defiance towards the political, economic, and media elites, perceived as a caste disconnected from all realities, starting with social and national realities. Successive disillusions linked to the classic exercise of suffrage have also played their role, as has the crisis of representation. People became tired of hearing promises which were never kept. First they found refuge in abstention, then in the “protest” vote, and finally in populism.

A few months ago I published a book on populism which sought to make a deep analysis of it. In it I asked myself particularly about the notion of “the people,” which one could understand as demos as well as ethnos or plebs. There are two things, concerning populism, that we must retain. The first is that it goes hand in hand with the collapse of the old traditional “parties of government,” which were also the principal vectors of the left-right divide. The second is that it substitutes to this old divide, of the horizontal type, a new divide vertical in nature, opposing the people to the elites. This opposition is decisive today: it's also the divide between the loser and the winners of globalization, the “non-connected” and the “connected,” the sedentary “peripheral” populations and a deterritorialized, indeed transnational, class, unreservedly adhering to the dominant ideology, to singular thought [Translator's Note: The original French term « pensée unique »is difficult to translate exactly, under the rule of « pensée unique »everyone must think the same. « Pensée unique » can be compared to « monnaie unique », « marché unique », « Dieu unique », etc.], and to the law of profit. It's this substitution of a vertical axis for the old horizontal axis that stops one from analyzing populism using terms and notions henceforth obsolete.

How to build a Europe of peoples without falling into the terrible errors of the past (Stalinism, Nazism, racism …)?

At least the errors of the past have the advantage of showing us what not to do. Moreover Stalinism and Nazism are typically modern phenomena, which inscribe themselves in the context of an era that has completely disappeared. Today's challenges, whether the grip of mercantile values, the migratory threat, ecology, artificial intelligence, etc, are of a very different nature.

The “Europe of peoples” will probably not happen tomorrow, which I regret. In the immediate future, what we must especially do is start from the base by reinvigorating the notion of citizenship and by creating the conditions for a more direct democracy. Only participative democracy, necessarily “illiberal”, can remedy the present crisis of liberal democracies. In other terms it means creating “free spaces,” be it at the level of the commune, the region, and the nation.

Globalization: who and what does it really serve? Do you find that it has only negative aspects?

Globalization is firstly another name for the planetary extension of the law of the market. It's the ultimate stage of postmodern capitalism. So its essence before all is on the economic, commercial, and financial order. The principal actors are no longer states, but multinational firms, financial markets, and the GAFA (Google, Amazon, [Facebook, Apple] etc.) That's why it differs from all past phenomena arising from simple internationalization. In the 19thcentury, capital could still partially serve national interests. Today it is totally deterritorialized. Financial transactions are done on the global scale at microsecond speed, relocation puts European workers into competition with those from low cost countries through a dumping effect, which is provoking a progressive disappearance of the middle classes, immigration exercises a downward pressure on salaries, and public debt further restricts governments' room for action.

From this point of view, I believe that globalization principally (but not only) has negative aspects. On the other hand, we must take into account a very important phenomenon which is that, like capitalism itself, globalization has its own internal contradictions. At the same time that it unifies, it homogenizes (peoples, cultures, ways of life), in reaction it incites new fragmentations, irredentisms, convulsive tensions that could be profoundly polemogenic [Translator's note: polémogène, giving birth to conflict]. We must understand globalization dialectically.

Why does the term “nationalism” always provoke fears and conflicts?

In reality it provokes many more fears than conflicts. The reason is that those who speak of “nationalism” essentially do so in order to denounce it, in an intellectually lazy fashion besides, as they've never made the effort to give it a precise definition. The word “nationalism” has become a catch-all concept, where they can put anything they want to conjure. It's the same with “populism” or “communautarisme” [Translator's note: communautarisme refers to the attitude of minorities, racial or sexual for example, to separate themselves from society overall]. But it seems that public opinion is decreasingly responsive to it, precisely because it sees well that what they say about it doesn't correspond to reality. If more than 70% of people today are hostile to immigration – while more than 70% of journalists are favorable to it – it's not that “racism” has suddenly seized 75% of minds. Words are not things.

Today, must we be pessimistic, optimistic, or realistic?

I suppose you guessed my answer. Actually it's a question I don't ask myself. Georges Bernanos said that optimists are happy imbeciles, and that pessimists are unhappy imbeciles. By definition history always remains open. We must only accept seeing what we see.

Source: http://www.girodivite.it/Europe-populisme-souverainisme-et.html