Reality and perception

There is no majesty to war, especially war as duel between two antagonistic class forces inflamed by unreconciled political differences. When an individual military theorist or a group of military theorists come together to critique their enemy or perceived enemy in terms of military strategy, then it is incumbent upon them to leave all prejudices aside.

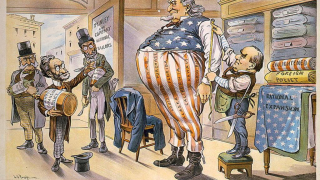

Since the end of the Second World War, the United States' military forces and its leadership have been besotted by a closeted hubris, a narcissistic pride before the god of war — that it is the greatest army in the contemporary, modern world. With this attitude of military exceptionalism, not seen since the time of building up of the Wehrmacht under the impetuous and Argus guardianship of Adolf Hitler, creative military theory among the U.S. military has died a slow, spasmodic death.

Few have equaled the wartime wisdom and prescience of U.S. army commanders like George Henry Thomas (1816 — 1870), an undefeated Union General during the American Civil War, who knew defensive and offensive strategy was a science and an art; he was more than willing to learn from studying European battles during the Napoleonic period, as well as clashes of antiquity.

To study the wars of the past is to understand present wars and future warfare. To defeat your enemy, you must study his army without hatred, without jealousy, without animosity. Keeping the above commentary in mind, allow me to give the reader my view on the Russian army in relation to U.S. army critique (although confined to a specific era) and analysis of its perceived enemy — its nemesis, the Russian Army.

This author does not claim to know the complex interworkings of the Russian Armed Forces, and therefore, I approach this theoretical analysis of the Russian Army with professional humility. I detest armchair generals, for they have no profound understanding of the true character of war with all its uncertainty, horror, and the lives ruined, a grisly carnival of carnage, flesh and blood being churned into the earth like it was nothing but fertilizer.

However, as a military historian myself, I will state that through vicarious experience one can develop a theory of war which can be put into practice by a patient methodology of scientific materialism, anchored to a tempered intellectual creative force. What I do recall in past studies of the Russian Army and its history is that the great military theorist, Carl Philipp Gottfried von Clausewitz (1780 — 1831), despite never engaging in actual combat was fortunate enough to serve with the Russian Army during his highly ingenious life before dying at 51.

Clausewitz had left the Prussian army, because he was opposed to the Prussian alliance with Napoleon Bonaparte. Switching sides for political and moral reasons regarding his view on the continental wars of his era, Clausewitz served in the Imperial Russian Army from 1812 to 1813. He would eventually write about the Russian Campaign against Napoleon’s invasion of Russia. His classic book, The Campaign of 1812 in Russia, had its effect on me in terms of amplifying my understanding the core military value of the Russian soldier.

In observing the modern Russian Army, viewed from the perspective of the American military analyst Timothy L. Thomas, a retired U.S. Army Lieutenant Colonel whose works include the 2015 study, RUSSIA'S MILITARY STRATEGY IMPACTING 21ST CENTURY REFORM AND GEOPOLITICS, I will only comment on certain sections of his book which I perceive as relevant to my discussion of military theory on the Russian Army in particular.

All wars do not have their own logic; that is, all wars are a part of the dialectical process of history. Therefore, to wage war, the military leadership must study overall and in detail the linkage of wars from small wars to large scale-wars fought between nation-states. Wars are not made in a vacuum of political and terrestrial isolation, but created and manifested by a series of socio-political circumstances in the tread of ongoing historical change throughout recorded antiquity.

One cannot conduct war simply by the ‘logic’ of war as having a course only of its own making, or as Thomas wrote: “If each war has its own particular logic, as Gerasimov proposed.” In the art of war the minute study of the objective and subjective analysis of any future combat can only be understand by the inclusion of the phenomena of history --military history in essence-- its core value can only be meaningful through linkage with past and living socio-political phenomena, not through nationalism and its hysteria nor religious values limited by messianic narrow-mindedness.

Certain Russian military theorists are mesmerized by the Germanic romance of Svechin’s strategy of ‘uniqueness’ for each given military conflict. There is no paradigm or model for contesting every given war, but there are universal values in conducting war based on common sense, astute pragmatism in the adjustment of tactical procedures brought about by dialectical and intellectual thought, fused with creative instinct. Although Timothy Thomas, the American military theorist, cites various Russian military advocates in their various military journals, he failed to propose practical procedures to counter Russian military thought as it is implicated on the battlefields of Georgia, Crimea, and the Donbass region of the Ukraine.

Despite this book by Timothy Thomas having been written relatively recently, in 2015, he did not reveal any illuminative insights on how he thought the Russian military forces might act in Syria. What should be acknowledged is that Syria has become a training territory for modern warfare regarding state-of-the-art ground, navy and air force combat tactical readiness and the use of direct force -- what Clausewitz termed 'the friction of war'. Syria like Spain during the Spanish Civil War is a breeding ground for pioneering tactical ways of creating war not only with innovative, modern methodology but also with cyber-war technology and drone aerospace warfare.

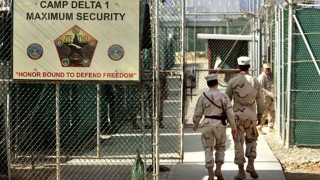

From my somewhat circumscribed perspective, I would state that the Russian advisors, the Russian Aerospace Forces, and in particular their navy forces equipped with long-range missiles, along with the Russian Special Forces, have shown energetic professionalism and élan in combat. Yet to be tested are the Russian troop forces in long-term combat situations, whereas the American army forces through action in Afghanistan and Iraq have been tested over the years and therefore battle-hardened, while lacking a profound moral sensitivity for fighting and dying in combat.

What should be noted, and was not addressed by the American tactician Timothy Thomas in his assessment of the Russian military, is how Russian military personnel are motivated by nationalistic pride. And like all nationalistic movements, their nationalism is limited by the forces of history, since no nation-state is exceptional, although some nation-states in both the East and West are naïve about how far they can imbue their people with the will to die for such a limited cause. Once Russian troops are killed en masse, captured or executed in real time, with bloody debacles seen on the various public media throughout the world, then we will have a better understanding of how the Russian autocratic regime in Moscow has reformed the Russian military.

The psycho-sociological tolls of battle are widely noted. We know in the United States, “Roughly 20 veterans a day commit suicide nationwide," according to new data from the Department of Veterans Affairs — a figure that dispels the often quoted, but problematic, “22 a day” estimate yet solidifies the disturbing mental health crisis the number implies. In 2014, the latest year available, more than 7,400 U. S. veterans took their own lives, accounting for 18 percent of all suicides in America. Veterans make up less than 9 percent of the U.S. population”.

Such statistics of those American veterans who kill themselves reveals their lack of moral commitment to recent wars they participated in for the Bush and Obama regimes. I predict these statistics will skyrocket as American troops become more involved in the civil war in Syria. One cannot exclude their possible adventurous forays which could take place in Libya, Yemen and even Korea in the coming months or years. Because of an unpredictable and perhaps even mentally unstable President, the United States Armed Forces are vulnerable, and this is a pattern that the Russian military leaders should study so as not to become, itself, in overreach outside the borders of Russia.