Halford Mackinder: The Geographical Pivot of History

Scientist and Politician

Sir Halford J. Mackinder (1861-1947) is one of the brightest figures amongst geopolitical scholars. Having received an education in geography, he taught at Oxford beginning in 1887, until he was named director of the London School of Economics. From 1910-1992 he was a Member of Parliament and in 1919-1920 he was the interim British Ambassador in Southern Russia. Mackinder is known for his high esteem in the world of English politics, and internationally, in which he was very notably influential, and also, by the fact that he created some of the boldest and most revolutionary systems for interpreting world political history.

For example, Mackinder most clearly depicted a typical paradox that is inherent in geopolitics as a discipline. Mackinder’s ideas were not accepted in the scientific community, despite his high position, not just in politics, but in the scientific community itself. Even the fact that he had actively and successfully participated in building English strategy in international questions, based in his interpretation of political and geographical world history, could not convince skeptics to accept the value and efficacy of geopolitics as a discipline.

The Geographical Pivot of History

The first and boldest of Mackinder’s works was his paper “The Geopolitical Pivot of History,” published in 1904 in “The Geographical Journal.” In this piece, he outlined his core views on history and geography that would be developed further in later works. This text of Mackinder’s might be considered the main geopolitical text in the discipline’s history, because he not only summarizes previous schools of thought in “political geography,” but also formulates the type of basic laws present in the sciences.

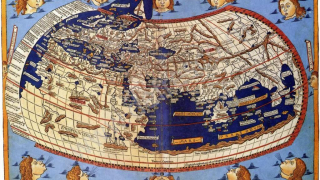

Mackinder claims, that for a state, the most advantageous geographical position would be in the middle, the central position. The concept of centrality is relative and it might vary in each specific geographical context. But from the global perspective, the Eurasian Continent lies in the center of the world and in its center—the “heart of the world,” or the “heartland.” The heartland is concentrated within the continental mass of Eurasia. It is the most favorable geographical springboard necessary for control of the whole world.

The heartland is the key territory within the wider context of the World Island. Mackinder includes three continents—Asia, Africa, and Europe—in this world island.

Thus, Mackinder hierarchizes global space via a system of concentric circles. In the very center is “the Geographical Pivot of History” or “pivot area.” This geographical concept applies equally to Russia. It is the same “axial” reality known as the heartland, “the heart at the core.” Continuing, “the interior or marginal crescent (inner or marginal crescent.” This belt coincides with the coastal spaces of the Eurasian continent.” According to Mackinder, the “inner crescent” itself is presented as the zone of the most intense civilizational development. This corresponds with the historical hypothesis that civilizations arose initially on the banks of rivers and seas, the so-called “theory of theories.” It should be noted that the last theory is a significant instance for all geopolitical constructs. The intersection of aquatic and terrestrial spaces is a key factor in the history of nations and states. This topic would be developed further as the specialization of Schmitt and Spykman; however, they were first brought out in Mackinder’s precise geopolitical formula.

Going further out to the next circle: “the outer or insular crescent” (outer or insular crescent). This whole outer zone (geographically and culturally is in reference to mainland masses of the World Island. Mackinder claims the entire course of history has been determined by the following processes. From the heartland’s center to its periphery, it is constantly under tension, from so-called “robbers of land.” Especially starkly and graphically reflected in the Mongolian invasions. But, they were preceded by the Scythians, Huns, Alans, and so on. Civilizations arising out of “the Geographical Pivot of History,” the deepest interior spaces of the heartland have, in Mackinder’s opinion, “autonomy,” “hierarchy,” “non-democratic” characteristics, and are “non-trading.”

In the ancient world, these traits were embodied in societies like Dorian Sparta and Ancient Rome. Tension is spread from the outside of these regions of the “island crescent,” to the world island by the so-called “robbers of the sea” or “island inhabitants.” With their colonial expeditions, springing from outside the non-Eurasian center, these aspirants counterbalance the terrestrial impulses, arising out of the interior margins of the continent. For civilizations of the “outer crescent,” characteristics are a “trading” nature and “democratic forms” or politics. In antiquity, these traits distinguished the Athenian or Carthaginian governments. Between these two civilizational poles, geographical impulses are located in the “outer crescent,” which are dualistic and constantly exerting opposing cultural influences that have the most mobility thanks to their priority positions in the development of civilizations.

History, to Mackinder, rotates around the continental axis. This history is more felt in the area of the “outer crescent,” than in the heartland, where frozen archaism “reigns” and in the “inner crescent” there is a certain civilizational chaos.

The Key Position of Russia

Mackinder himself identified his interests with the interests of the Anglo-Saxon World Island, i.e. of the position in the “outer crescent.” In that station, he viewed the fundamental geopolitical stance to the “world island” to be the maximum weakening of the heartland and in extending this influence to the furthest possible limits of the “external crescent” within the “interior crescent.”

Mackinder stressed the strategic priority of the “Geographical Pivot of History,” and he conjectured that that throughout the political world this was the paramount geographical law.

“The one who controls Eastern Europe dominates the heartland; he who controls the heartland dominates the World Island; he who dominates the World Island dominates the world.” (“Democratic Ideas and Realism”) (10) At the political level this means an admission of Russia’s leading role in strategic thought. Mackinder wrote:

Russia, as well as Germany, occupies a central strategic position in the world as a whole, and in Europeans relations. It can carry out attacks in all directions and be subjected to them as well, except form the North. Complete development of railway capabilities is a matter of time. (“The Geographical Pivot of History”) (11)

Proceeding from this, Mackinder considered that the main objective of English geopolitics is to prevent the organization of a strategic continental union around “the geographical pivot of history” (Russia). Accordingly, the strategic power of the “outer crescent” is the ability to pick off the maximum amount of coastal space from the heartland and place it under the influence of “island civilization.”

A disturbance in the power equilibrium towards the “pivotal state” (Russia and others), accompanying its expansion into the peripheral spaces of the Eurasia, will allow it to use vast continental resources for the creation of a mighty, seafaring fleet: this brings it closer to world empire. This will be possible if Russia unites with Germany. The threat of this development will compel France to enter into an alliance with oversea powers—and France, Italy, Egypt, India, and Korea will become coastal bases for the mooring of the Great Powers’ fleets to pulverize the forces from the “pivotal range” from all directions and thwart their efforts to concentrate forces into a powerful, naval fleet. (“The Geographical Pivot of History”) (12)

Most interestingly, Mackinder did not just construct simple theoretical hypotheses, but actively participated in the international organizations supporting. the Entente’s “White Movement,” which he considered to have Atlanticist tendencies—directed towards weakening the power of the pro-German minded Eurasianist-Bolsheviks. He personally consulted with the leaders of the Whites and tried to gain maximum support from the English government. It seemed he prophetically foresaw not only the Treaty of Brest, but also the Molotov- Ribbentrop Pact.

In his 1919 book “Democratic Ideals and Realism,” Mackinder wrote: “What will become of the naval forces if one day the great continent is politically unified to become the foundation of an invincible armada?” (13)

It is not hard to understand why exactly Mackinder established in Anglo-Saxon geopolitics, which in half a century would be the United States and NATO, this essential tendency: to impede in any way capable the very possibility of the creation of a Eurasian Bloc—established through a union of Russia and Germany—a geopolitical reinforcing of the heartland and its expansion. The West’s sustained Russophobia in the twentieth century is not just ideological, but also geopolitical in character. Still, taking into account Mackinder’s connection between civilizational types and these geopolitical characteristics, or other forces, one could acquire a formula for which geopolitical terminology is easily translated into ideological terminology.

The “outer crescent” is liberal democracy; “the geographical pivot of history” is non-democratic authoritarianism; the inner crescent is an intermediate model—a combination of both ideological systems. Mackinder participated in the preparation for the Versailles Treaty, which would reflect the essence of Mackinder’s views. The treaty was designed to instill a Western European character in the coastal bases for naval forces (The Pax Britannica). Together with this, he envisaged the establishment of limitrophe states, which might divide Germans and Slavs, in every way discouraging a strategic continental alliance between them that would be so dangerous for the “island countries,” and accordingly, “Democracy.”

It is very important to trace the geographical bounds of the heartland in Mackinder’s works. If the years 1904 and 1919 (corresponding with the article “The Geographical Pivot of History” and the book “Democratic Ideals and Reality”) the shape of the heartland coincides with the outline of the borders of the Russian Empire, later the USSR, and in 1943, in his text “The Round World and the Winning of Peace,” he reevaluated his former views and withdrew the Soviet territory of Eastern Siberia—located past the Yenisey River—from the heartland. He named the sparsely populated Soviet territory “Russian Lenaland,” after the Lena River. Russian Lenaland has nine million inhabitants, five million of whom live along the transcontinental railroad between Irkutsk and Vladivostok. In the remaining territories, there is less than one person per eight square kilometers. There are great riches particularly untouched in this wilderness—lumber, minerals, etc. (“The Round World and the Winning of Peace”)

The removal of so-called Lenaland from the boundaries of the heartland meant that he considered that territory’s potential to zones of the “inner crescent,” such as those coastal spaces, capable of being used by “island” nations in the struggle against “the geographical pivot of history.” Mackinder actively participated in organizing interventions by the Entente and “White Forces,” apparently considering Kolchak to be a historical precedent—resisting the Eurasian center—considered to be basically sufficient for controlling its territory by way of potential “coastal zones.”

Three Geopolitical Periods

Mackinder divides all world geopolitical history into three phases (16):

1. The Pre-Columbian Epoch: In this phase, nations, belonging to the periphery of the World Island, for instance the Romans, living under constant threat of invading powers from the “heartlands.” For the Romans, these were the Germans, Huns, Alans, Parthians, and so on. For the oikumene of Central Europe, it was the Golden Horde.

2. The Columbian Epoch: In this period, governments of the “inner crescent” (coastal zones) set off on invasions of little known territories around the globe— nowhere meeting serious opposition.

3. The Post-Columbian Epoch: Large unconquered lands no longer exist. Dynamic civilizational ripples are doomed for a collision—compelling nations into a global civil war.

Mackinder’s periodization-with the relevant geopolitical transformations—leads us closer to the newest tendencies in geopolitics, which we discuss in the next sections of the book.