György Schöpflin: Illiberalism of Orban, modern Hungary and positions of Fidesz

Interview of Geopolitica.ru with Hungarian politician and Member of the European Parliament from Hungary, member of Fidesz György Schöpflin.

In your opinion, what is the biggest lie of liberalism?

The biggest lie?

Or the biggest illusion of liberalism.

Illusion and lie are not the same thing. I mean a lie is a conscious, deliberate falsehood. An illusion may be a misunderstanding, an error in perception. My experience with the liberals I encounter is that they are firmly convinced that what they say is right. They have an illusion. They have a fallacy. But I think that in grand intellectual, historical terms, what has happened is that classical liberalism has been transformed, that of Tocqueville, John Stuart Mill…or Francis Lieber, a German-American, who wrote in the second half of the nineteenth century. He was a contemporary of Tocqueville’s. I don’t think they ever met. Their starting point was that the individual has certain inalienable rights. We can, by the way, trace that back to Christianity. You can find various roots. And I think this has now been magnified to such an extent – distorted, if you like – that there are only rights, and there is only the individual. And my argument is that, as individuals, if we do not have some collective identity, we’re lost. We lose our humanity. Now, what that collective identity is, well, there is an infinite variety. It can be a trade union. It can be a regiment. It can be a school. It can also be a nation. Civilization? I don’t really know what a civilization is, but we can argue about it.

So then the question is to what extent does that collective identity determine the individual’s worldview? And I think that it does, but it still, depending on the identity we’re talking about, leaves quite a lot of autonomy for the individual. But I think what has happened is that the current iteration of liberalism denies all collective identity, or comes very close to it, because it believes in a single, universal humanity. Well, very nice. Yes, I think there are a few qualities that all human beings have. Basically, we all have two lungs and one heart, but the moment you reduce humanity to a single entity, you eliminate cultural variation. You are unable to understand quite a wide range of phenomena which you then condemn. “It’s deviant, wrong, morally unacceptable,” and so on and so forth.

To me, I think this is the flaw, the error of liberalism, which I think today – it wasn’t necessarily so twenty years ago – has become linked to a utopianism and has become linked to a sense of mission, that liberals are sent by themselves, or history or humanity, or whoever, to save the world.

Now, I’m sure you’re familiar with salvationism. Soteriology is the technical term. I do see this – not obviously in every liberal, but they have a very, very strong belief in their own correctness which may not be questioned. At that point, I think one has departed from what I understand to be the liberal tradition: that you remain open to dialogue, you remain open to discourse, because if you don’t, then you generate a frustration in your interlocutor. And that frustration can result in pretty negative consequences. Indeed violence, in certain circumstances. You know, when you have social tensions accumulating, and there’s no other way of resolving them, you may get an explosion, of which there are countless examples in history.

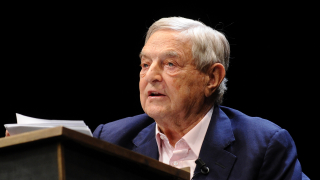

Interview with György Schöpflin. Photo: Geopolitica.ru

What will happen to humanity in the liberal paradigm when we see the eternal division in everything, the reign of quantity. Many of us are losing collective identity. Even the individual has become like a jigsaw puzzle, where you can replace his hand, or maybe eventually even his brain, with electronics. It’s the old philosophical problem of division, so what do you see . . .

Which division do you have in mind?

I mean the principle of division.

I think I see what you mean. Binary opposition?

Also. For example, we had people, identities, big families. Now we see that in big cities there are individuals, individualism like a principle, and it is an example of this division. And even one person is sometimes no longer complete.

So this is the divided humanity.

Yes.

Well, I think that that is our legacy. I think that you can’t, in my view, find wholeness. You can try to be holistic, but you can never reach it, because it’s our basic heritage that there will always be divisions and contradictions and dissonances in what we are and what we do, how we respond to different situations, and I don’t want to get too biological, but I think that in certain circumstances biology plays a role: I don’t know, whatever you’ve eaten. Did you have a good lunch? If you had a good lunch, you feel better, etcetera, etcetera. In a word, the contingency of life.

So I’m simply saying that it’s the infinite diversity, the infinite variety of possible responses, and that kind of division will always exist. The role of the ruler, of society I think is to establish some kind of order, otherwise there’s chaos, some kind of stability, and perhaps just as much as anything else predictability. Broadly speaking, you can evolve a strategy, which may change over time, that, on the whole, things will be much the same tomorrow as they are today. If that is upset, if you have arbitrary action which transforms the predictability, then I think you get a lot of negative consequences.

What do you think of the idea of illiberalism?

The term illiberalism is, of course, not mine. The term illiberalism was propounded by the Hungarian Prime Minister, Viktor Orbán. Note that, to the best of my knowledge, he only ever used that word once, I think several years ago (in 2014). It has acquired a set of meanings which have been attributed to that word, and indeed to Orbán, by outsiders. What I see as illiberalism, which may not correspond to anybody else’s view, is a questioning of extreme individualism, the questioning of inequalities. I’m not a radical egalitarian. There will always be differences. But I think that the levels of material, and also cognitive, inequality in the world are, for me, morally unacceptable. Not just between, let’s say, the rich West and Africa, but within European states.

There is a very interesting French social geographer, Christophe Guilluy. He basically argues that centre-periphery has come into being within France, and I think one can apply that insight to pretty much every European state. Probably Russia, too, actually, if I think about it – I suspect that certain parts remote from the centres are pretty marginal. Or the Western country that I know best, which is Britain. I’m sure you’ve been to London. Glittering world city, everything, and then if you travel north, to northern England, you see a very, very different country. Not material poverty, but intellectual poverty, cognitive poverty. Meaningless lives. And it’s that kind of inequality that concerns me, which I think is a consequence of the proposition that markets solve everything. I think the State does have a role. Where that role is, where is the dividing line between State and market, it’s always going to be a matter of argument.

What we had in Hungary, and this is where the Hungarian version of illiberalism comes in, is that we had a Left-wing government from 2002 to 2010 which pursued extreme market liberal policies, the consequence of which was close to bankruptcy for the State. Very close. Almost. When the Fidesz government was elected in 2010, it discovered that the deficit left behind – I’ve forgotten the exact figure – was far greater than what anybody understood, the net result of which set the country very close to the kind of bankruptcy – collapse – that Greece entered. So basically, Orbán took a decision – you know, each European Union country has to maintain its deficit within three percent – he went to Brussels and said to Barroso, “We’ve inherited this problem. Can we have some easing on the three percent?” And Barroso said, “No.” So at that point Orbán understood that Brussels, the Commission, was not going to be very well-disposed towards his government. What they really wanted him to do was to introduce an austerity policy which, in a relatively poor country like Hungary (this is no longer quite so acute), would hit the most marginal very hard. It was already tricky. It’s not so true now, but in some parts of Hungary there were children who basically had next to nothing to eat from Friday until Monday because their parents couldn’t afford very much to eat, so they’d only eat at school. This is appalling. In my humble opinion, I think this is intolerable in a moderately well-to-do, medium-sized European state.

So there was no way that the Fidesz government was going to accept a restrictive policy that would hit those marginal sectors of society, strata, even harder. So, the government introduced a so-called unorthodox policy of taxing internationals, taxing banks, taxing telecoms, multinationals, thanks to which the worst was avoided. This was extremely unpopular in Brussels because it went against the conventional liberal orthodoxy, which, at least in my view, has captured Brussels. It is unable to think in different terms, and from that perspective, Hungary became deviant. Nobody likes deviants. Deviants have to be brought back into the “liberal” fold.

So when Orbán made this speech at Tuşnad, he said, “What we’re building here is an illiberal state. Of course, we maintain all the classical freedoms.” Now, that’s the bit that everybody forgets. That speech has to be studied very closely. The illiberalism that Orbán was talking about is basically a form of etatism, that the State has a role to play in social protectionism. And by the way, this is not that far from either Christian democracy or social democracy, but liberalism has done something else, very interesting in grand historical terms: it has established a monopoly over democracy. If you’re a democrat, you’re going to be a liberal democrat. I don’t accept this position. I think there are all sorts of different forms of democracy. And in that sense, Orbán’s illiberal perspective is well within the confines of democracy.

Now for me – because I think this begs the question of what I mean by democracy – it is a system of power where rule is by the consent of the governed, and that there is a degree of institutional pluralism. What degree? Well, we’ll argue about that. Rule of law, checks-and-balances, sure, etcetera. So that’s how I would define illiberalism. It’s not an absolute concept, to some extent it’s fluid, what you accept as being within it, what you accept as outside of it. But I would add again that this is not the way in which it is used by much of the Western media. For them, illiberalism is very close to the devil. It has acquired a demonic content that almost seems to have become a semiotic code. You say the word “illiberal” and you automatically associate it with otherwise undefined phenomena. Very, very interesting. It has even got a strong metaphorical charge, which means you can’t deconstruct the word “illiberal” because it’ll not be heard, because it’s already so strongly established that it excludes alternative definitions and meanings. I think you will recognize this as being very close to Bakhtin’s monology.

What are the factors that make Fidesz popular?

First of all, the economy is doing quite well. I’m not a Marxist, I’m not a materialist, but I have to accept that, yes, the fact that the economy is doing well in some sectors – there is even a labour shortage in skilled manual labor, mostly – we have been going up slowly, but still well behind Germany, or Austria for that matter. But still, there’s an improvement, and it’s palpable. And there’s been quite an impressive visual change in infrastructure – it’s not all there, and the railways are still not very good, but still. The motorways are not doing too badly. Support for the family is one of the best in Europe. Health has taken a lot of cuts. Not good. And what sits close to my heart, of course, is education. Education is always the easiest target for a government that wants to cut spending, and that’s always easy to do. In those two areas especially, considerable monies will have to be spent in time to come.

Then, I think the stand that the government took in 2015 on migration has been of central significance. Now, I don’t know if you’ve seen the pictures – because I’m sure you weren’t in Budapest in the summer of 2015 – these unbelievable pictures of the Eastern railway station, of the Keleti . . . It was a form of structural violence. Basically, it’s unimaginable to me that two hundred thousand plus – maybe more, I’m not sure how many people – just simply walk through Hungary as if it didn’t exist. A country which cannot control its frontiers, which cannot control who comes into that country and who does not, unless there’s a derogation like Schengen, is not a proper country in the Weberian sense, because I think it is a part of the monopoly of legitimate violence for a State to be able to say, “You can come in and you cannot.” Now, this having deeply shocked Hungarian opinion, certainly the people I spoke to – well, I think I can fairly say I was shocked myself – it’s pretty shocking to see a scene that is fairly familiar to you suddenly transformed in a way that is beyond the control of the State.

So I think that that general experience, it was traumatic for quite a lot of people, because they’d had no idea, they’d never had experience of this number of people. I mean, Budapest is already very different from what it was fifty years ago. Obviously tourists started coming. Fine. But that was something completely different. And I think the fact that the government as such took a very strong stand on migration, built the fence, and said, “No, you can’t come in here just like that” . . . And this again was distorted in the Western media. They depicted the fence as something to stop people from coming in. No! The fence was there to ensure that people went to the frontier crossing point where they could be registered. And registration takes time, so there’s no way that one could register two thousand people a day. Some people got stuck on the Serbian side, or they went off to Croatia, but gradually, over time, I think much of European opinion has come to accept that Europe can’t absorb this number of migrants. Hungary has, to the best of my knowledge, not accepted any migrants, we’ve accepted refugees. That’s a distinction that I think is well worth making. The Geneva Convention: if you’re in fear for your life for political reasons, or you come from a war zone, that sort of thing, then of course you will be given political asylum, refugee status. If you’re an economic migrant, then Hungary doesn’t need economic migrants.

And then of course you get into the whole problem of the dispute between Hungary and Germany over Willkommenskultur, over Merkel saying, “Let everybody come,” but – come through Hungary? Excuse me? Merkel basically imposed Willkommenskultur on Europe, without Europe’s consent. Certainly without Hungary’s consent. So that friction, that tension, remains of course . . . In Europe today, Germany is a preeminent partner – I say partner, because we’re in a partnership – but we do have disputes, and that’s one of them. I think also that Hungary, you have to understand, is a deeply conservative country. Conservative not in the political sense necessarily, but in a cultural-sociological sense. To give you one illustration, in terms of music, I think this country is still in the 1930s. Contemporary music simply has no reception. People haven’t learned the language of Stockhausen. You may not like Stockhausen, but you still have to accept that he’s one of the major figures in European musical terms. I think one of the great composers of the twentieth century is Villa Lobos. Unknown in Hungary. In that sense, culturally, there is a great deal of conservatism, reluctance to accept the new. You can trace this back to a series of repeated traumas. Now, you may be familiar with cultural trauma theory. After such traumas, society becomes defensive and introverted, and tries to save what it can.

I’m not going to take you through the twentieth century history of Hungary, but before 1914, this was a very self-satisfied and successful society. Look around Budapest today. This building where we are, the Gresham Palace, was built in, I think, 1906. It’s been beautifully restored. I like it very much. And there was enormous self-confidence about building a really major European city, which I think was quite successful. Then you have this series of shocks, traumas, and changes viewed very negatively: the Second World War, 1956, to some degree even the system change in 1989, and this sense that things are happening to us without our ability to affect them, to influence them, even to change them. It’s in that sense that this is a conservative society. And one of the things that I believe Orbán, and indeed the Fidesz government, is trying to do is to change this, to give Hungarian society self-confidence – it’s happening slowly – and at the same time, to define a particular Hungarian version of modernity. What does it mean to be modern and Hungarian?

Now, the liberals will tell you there is only one modernity. This is not true. It’s simply not true on the evidence.

Have you ever been to Japan?

No.

Well, basically, Japan is modern, but it’s very differently modern from Germany or France or Britain, and it’s in that sense that there are multiple modernities. This thought is anathema to a universalist. And that’s why, of course, for me illiberalism conveys this idea of the Hungarian road to modernity. If you want to use the Marxist-Leninist terminology, it’s a polycentric modernity. Think about the 1960s. So it’s in that sense that I would define illiberalism, not in the sense in which the various organs of the Western media try to do it.

That’s a very interesting explanation. I also have a question related to your article, about the politically segmented society and the possibility of civil war. What precisely did you mean by it in relation to Hungary?

Okay. Segmentation theory, I use this in a fairly classical sense, based mainly on the work of Furnivall, who was writing about Burma, and I think Indonesia, before the Second World War. He was a very interesting figure. He was an anthropologist, and I think also a colonial civil servant. I don’t remember exactly. And what he writes is that there are different ethno-social religious groups which lead their own lives, so you have a state in which state and society are not coterminous. You have different segments operating. This, of course, was also the Austro-Hungarian Empire. How do you deal with this if you want to have something like a citizenship, then have to do one of two things: you can try to suppress the segments, which then generally ends up with the most powerful segment suppressing the others. It’s basically the Russian Empire before 1914. Think about Uvarov: autocracy, Orthodoxy, the Czar, and so on. And the smaller segments have to conform, have to adapt. One of the problems of being in a minority is that you never own the narrative. The narrative is always constructed by the majority, which means that if you have a segmented society, you will always have resentment. Probably ressentiment is a better word for that: a deep feeling of not being central against the problem of agency.

What I see in Hungary – and I don’t like it, but that is, I think, the sociological reality – is the existence of probably three segments. Maybe four, possibly five. It depends on how you define them. Politically, the divide between Left and Right is very, very deep. Fascinating – there is a hereditary transmission of segmental identity, so if you are born to a Right-wing family, the chances are very high that you, too, will be Right-wing, and vice versa. To some degree – not purely, it’s not a one hundred percent overlap – the Right are the descendants of the victims of Communism, the Left are the legatees of the nomenklatura, the beneficiaries of Communism. And Communism did have its beneficiaries, let’s be quite clear on this. So that’s two segments.

The third segment is the radical Right, which we will see . . . Well, first of all, Jobbik is no longer quite as radical Right as it once was, it’s trying to move in towards the centre, with what degree of sincerity I’ve no idea. What I can say about Jobbik is that they were pretty amateurish ten years ago. This is no longer true. They’re quite professional, and they’re all very good at using social media. They, too, have a vision of modernity. I think there is a very hard radical Right in Hungary, sort of seven to eight percent, and then the other bulk of Jobbik . . . Difficult to say, but in 2010 and 2014, much of the disaffected – very often underemployed or unemployed blue-collar strata – shifted from voting for the Left to voting for Jobbik. They don’t shift to Fidesz, they shift to Jobbik because they are radical. This isn’t well understood. If you’re radical, you don’t care whether you’re radical Left or radical Right. You’re radical. There are lots of historical examples. It’s the radicalism that moves you. So that, I think, is one segment.

And indeed, if you want to break down the support for Jobbik, you find support in the rust belt of the northeast – in Miskolc, around there. Some of them in Budapest. There’s a very interesting stratum of radical university students, almost all male, students who are anti-globalization. That, I think, is not just a Hungarian phenomenon. And then you have a very interesting phenomenon: the inroads that Jobbik has made in some of the smaller villages, especially in Transdanubia, who don’t starve, but they don’t have the opportunities which you get in the larger towns. So they’re resentful, and Jobbik has been able to pick up their vote. Whether they’ll get the fifteen percent or so on 8 April (the date of the parliamentary elections), I don’t know. They will probably do quite well. So that’s my third segment.

I think a fourth segment is the Roma, probably a fifth segment being the third-largest Jewish community in Europe, which is overwhelmingly a Budapest community. They have a sense of separateness – to what degree or what extent is another matter.

So if you look at this, how do you then establish a citizenship which is acceptable to, let’s say, ninety-five percent of the population? Probably, the Jobbik segment will accept most of the nationhood, though Fidesz is not radical enough for them. The Left will never accept that. The Left, I think, still denies the constitution, the basic law. They say that, “We want to change it.” Well, that’s politics. I think the Roma are reasonably content with the ideas of national citizenship. Nationhood, I don’t know. Some of them do feel they’re Hungarian, some of them think they’re Roma. It’s probably a mixture.

But then you get this problem of what does citizenship and modernity mean, and indeed liberalism and the role of the State, if you’re in one of the segments that is not the Fidesz segment? Well, you have to adapt, you have to adjust. Majoritarianism doesn’t work perfectly because there will be, as I said, those who reject the majority position, particularly with the Left-wing segment that is different. I don’t think in Hungary anybody thinks about power-sharing or consociational solutions such as you used to have in the Netherlands and you still have in Belgium, Austria to some degree, and lots of examples from before the First World War.

In Moravia, the population was sixty percent Czech and forty percent German, or sixty-five, thirty-five, and in 1905 they came to a power-sharing agreement which would ensure that both parties were proportionately represented in political power so that ethnic identity, language, was no longer a central issue in the political contest.

In Estonia in the interwar period they introduced a similar arrangement, that the Germans, the Russians, Jews, the Swedes – these were the four minorities – would all establish corporations and be responsible for their own educational and cultural life and they would tax their members. They would, of course, accept Estonian citizenship and the Estonian state. The German corporation worked reasonably well. The Russians never got round to setting it up because they kept arguing. Remember that in Estonia there were two groups of Russians: the urban Russians of Tallinn and Narva at that time, and then the Old Believers. There was a community of about ten, twelve thousand Old Believers at Lake Peipus, and they never managed to get this together. The Jews were about to do it when the war broke out. The Swedes, very few in number, they were territorially compact, so they didn’t need it. But the system worked adequately. Not perfect, but nothing is perfect. If Estonia had not been absorbed by the Soviet Union in 1940, then, of course, that experiment would have been continued.

So, that kind of power-sharing agreement can work. It requires the majority to accept that it can only run the country properly or adequately or sufficiently if it has the consent of the minority. That’s what a system of that kind does in terms of segmentation.

I would like to ask you about the Russian-Hungarian, or rather Hungarian-Russian, relationship . . .

They’re not the same. Hungarian-Russian and Russian-Hungarian are not the same, but both are significant.

We see that between Hungary and Poland there is diplomatic cooperation, and between Hungary and Russia there is cooperation, but between Poland and Russia there are big problems. First, will Russia be a problem in the relations among the countries of the Visegrád Group, and second, how do you see the relationship between Hungary and Russia?

On the Visegrád point, it obviously creates a certain amount of friction between Hungary and Poland, but then there is so much else which brings the V4 countries together that the two countries, I think, have agreed to disagree. Broadly, Hungary accepts the “Three Seas” idea. And there’s a second point that ties in with the second part of your question. Hungary is very largely dependent on Russian energy. Poland is not. If we had a sea coast, it would be different. We’d be able to import liquefied natural gas on the global market. The pipelines are actually now an outdated technology compared to the LNG.

The problem is that about eighty-five percent of Hungarian energy, overwhelmingly gas, comes from Russia. So we have this transactional relationship with Russia where, whatever we do, we’re dependent on Russian gas. I would add that both the United States and the European Union have been very slow in recognizing this kind of dependence. They’ve been much faster in recognizing the particular problem in Lithuania. Lithuania, for a long time, was an energy island. It isn’t anymore. They’ve linked their power grid across the sea border with Sweden, and they have this LNG terminal in Klaipeda. So it’s transformed Lithuania’s dependence. Of course, Lithuania still buys gas from Russia. There’s an LNG terminal being built in Finland, and there is one in Poland, in Świnoujście. The problem is the interconnectors to Hungary are not there, and actually, Gazprom has done everything to stop it.

The other possibility is an LNG terminal in Croatia, and the Croats have been very, very slow in doing anything. Since I first heard about this in 2007, that there was going to be an LNG terminal on the island of Krk – nothing. Slowly, under the present Croatian government, they’re beginning to do something, and my understanding is that Hungary at one point asked Washington, “Could you help? Could you persuade the Croats to start building this?” And the Americans said, “But why? You’re buying this gas from Russia.” And we said, “We don’t want to be too dependent.” “Don’t be paranoid. It’s a commercial transaction.” Well, it never was. From the 1990s already, Russia was talking about the “energy weapon.” But the Americans never understood this.

So we’re left in this situation of being energy dependent on Russia. Fine. Acceptable. It didn’t raise eyebrows. And then came Crimea, and at that point the political context completely changed. So, Hungary’s relationship with Russia became objectionable. Interestingly enough, Austria’s relations with Russia is never questioned. Germany, determined to build Nord Stream 2: no. Hungary: yes. I’m neutral on nuclear power. I don’t have a strong position on it. Rosatom offered to extend Paks, and the Orbán government considered it. The terms were very good. I’m not sure that Rosatom really has the money for this, but we’ll see. Rosatom is very ambitious, building nuclear power stations everywhere. We’ll see. The terms were very advantageous, and on top of that, there is a strong technological argument in enlarging Paks with Russian technology. It will cut costs in all sorts of areas if you use the same technology that you have already. I know that Westinghouse also offered, and apparently the terms were much worse, and they said, “We will enlarge Paks.” And the Hungarian government said, “This is an absolute impossibility. American nuclear technology and Russian nuclear technology simply won’t mix.” And Westinghouse was apparently very angry.

So in that sense, it’s the energy area. Where I would say I’d like to see more investment now is in renewables, and there I think we’re still very slow. We probably could be generating much more of our electrical power from renewables. There are some wind farms. Not many. I don’t know how many in Hungary. More than there were ten years ago. Solar panels, much more remains to be done. The cost is dropping all the time. Chinese solar panels are very cheap now, and as you probably know, it’s not the heat, it’s the light that generates the energy.

I don’t myself see any strong ideological overlap between Fidesz’s position and Russia. Yes, Putin was here. He did go to the cemetery in Kerepesi út to lay a wreath at the memorial to the Red Army soldiers killed in 1956, and so on, which I think is a bit difficult for a Hungarian to swallow, because the Russians who were killed in the 1956 were here as an invading force. They were not invited. But basically I think that, obviously, there will be individual exceptions. People who are involved in trade with Russia want to have maximally good relations, as you would expect, and they’re opposed to the EU sanctions. Hungary has followed the EU sanctions, and I can’t see any reason why that’s a problem. There’s a certain level of EU solidarity, and it was the Budapest Memorandum that Russia violated over Crimea. This has a certain sentimental resonance. That in exchange for Ukraine abandoning its nuclear armoury, Russia guaranteed the territorial integrity of Ukraine, only for so long.

So I don’t myself see great depth in Hungary’s relationship with Russia. From the other side, I think Hungary is completely marginal as far as Russia is concerned. You can use it to make trouble, but not more than that. There are much more important countries with which Russia has to deal. Germany, that’s the most important EU country for Russia, not Hungary, and it’s slightly absurd for Hungary to imagine that it is important. Where it becomes significant is if ever the European Union cohesion and structural funds dry up or diminish, then the opening to the East – Russia, Central Asia, China – can become significant as a source of investment. That’s as far as I would take it, but you’ll find others who take a different view of the Russian-Hungarian, Hungarian-Russian relationship. But that’s my take on it.