Dabiq and a Skewed Revolution: Two Discourses at Play on Syrian Soil

Introduction

This article conducts a discursive analysis of an article published by the Islamic State of Iraq and the Levant (ISIL, also known as ISIS, IS or Daesh) in its magazine Dabiq1, published periodically in the English language for purposes of propaganda and recruitment. The article in question, The Allies of Al-Qa’idah in Sham: The End, was extracted from the twelfth edition of Dabiq, entitled Just Terror, issued shortly after the so-called Paris Attacks were claimed by the group on November 13th, 2015. In it, the Islamic State presents three documents released by “Syrian revolutionary factions” fighting them on the Levantine battleground, on which they afterwards comment in disavowal. Given this convenient format, our analysis is allowed to put on a comparative mould, as I will be observing both the ISIS discourse and also that of their opponents, pointing out, wherever necessary, parallels and contrasts between them.

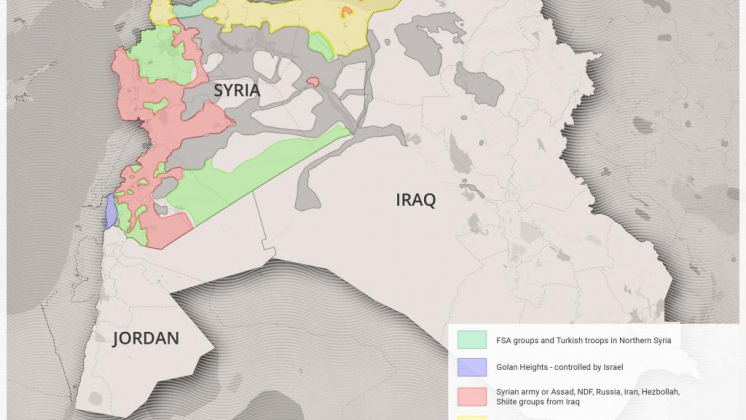

For purposes of analysis, the groups signing the three different documents aforementioned will altogether in this paper be referred to as the “Syrian rebels”. The most prominent signatory factions they’re composed of are the Free Syrian Army, Harakat Nour al-Din al-Zenki, Shamiyyah Front, Faylaq ash-Sham, Jaysh al-Mujahidin and Al-Ittihad al-Islami li Ajnad ash-Sham. They are the so-called revolutionary groups who, claiming the immediate overthrow of president Bashar al-Assad’s regime, have in a strict sense been backed by the UN and the US-led military coalition since the beginning of the Syrian conflict, in early 2011. It should be noted that the conclusions presented here do not necessarily reflect the current situation in Syria, but rather the one prevalent as of November 2015, as we’re dealing with an ongoing and swift flow of events.

The paper’s structure begins with a merely textual analysis, followed by an interpretation based on the process of the text’s production and reception, and, at last, by an attempt at explanation through the socio-historical conditions at play. Our main interest is to present how terrorism discourses can be mobilised to pursue geopolitical goals and produce profound changes in the political world map; how the use of terms such as “terrorism”, “foreign intervention”, and “democracy” is made relevant not only in the Western information war, but also in the balance of force on a real battlefield; and, lastly, how otherwise locally marginalised political groups can lean on a dominant international discourse in order to attain power.

Textual Analysis

Two out of the three Syrian rebels’ documents exposed in the article, all issued between late September and early October, 2015, are presented in the format of topics. The third one, though being an excerpt from a more flowing text, is called The Five Principles of the Syrian Revolution. They are addressed towards the United Nations, its envoy for Syria (that is, the Italian-Swedish diplomat Staffan de Mistura), and the Western world in general as the basic conditions and demands for the Syrian revolutionaries to agree on a process of regime transition in the Syrian political sphere. To facilitate the reference to each text, they’ll be identified by the order in which they appear on the article.

Working against this background, it is important to explain certain choices of words and rhetoric in their messages. In the first place, it is feasible to believe that, in order to hold such an important position as that of a major interlocutor in the decision of the nation’s future, it is imperative for the Syrian rebels to present themselves as a truly legitimate representative of the Syrian people, with no trace of innocent Syrian blood on their hands.

Therefore, it is made evident in many passages that the rebels’ legitimation is drawn from this abstract category of the “people” — the emphasis upon which exposes the commitment of these groups to convince the UN of their sharing Western democratic and secular values. This is crystal clear in passages such as “The Syrian people, the launchers of this revolution, (…)” (second document, first paragraph), in which people and rebels are presented as equivalent and interchangeable. Thus, legitimation on the part of Syrian rebels is derived from both authorisation — the people as a source of legitimate authority — and moral evaluation — as there is an underlined moral statement in appealing to that particular authority, i.e., the democratic and secular claim that the people are the ones morally entitled to decide how things ought to be done.

In terms of lexicalisation, it should be noted that every group defined as “terrorist” in the rebels’ discourse appears linked to the Assad regime, their main opponent, in one way or another. They claim to “reject overlooking and being silent about the terrorist groups that the Assad regime summoned to Syria” (first document, fifth clause), citing as examples, more than once, the Iranian Revolutionary Guard and Lebanese Hezbollah, but make no mention of terrorist groups fighting Assad on the ground. There is only one reference associating the Islamic State with terrorism (second document, third principle), in which it appears, curiously enough, on a list of key allies of the Syrian government. To this, even the Dabiq (IS) editor adds a footnote clarifying:

“Editor’s Note: The Sahwah factions because of their religion of nationalism are not able to differentiate between the Rafidi apostates (the apostate Iranian Revolutionary Guard, Hezbollah, Abul-Fadl al-‘Abbas militia, etc.) and between [sic] the muhajir mujahidin (the muhajirin of the Islamic State). The Rafidah are apostates even if they are “fellow Syrians,” and the muhajir is a Muslim even if he had been a Christian American before his Islam. (…)” (p. 13)

Again in the third document, the fourth clause abandons subtle associations to openly and explicitly claim the existence of “compelling evidence on full coordination between the two sides and the role Assad’s regime plays in the emergence of ISIS”, a statement which ISIS rebukes with an even longer and more spirited footnote. As we’ll explore later, these are all examples of how the concept of terrorism and groups easily associated with it in the common sense (in this case, IS) may be used as a weapon like any other when targeting an enemy, striking powerful blows in the field of public opinion — which can be said to be as fundamental to win a war as the real battlefield, inasmuch as the sphere of ideas and discourses is the place where alliances may be promoted or severed, as well as where military interventions may be triggered.

Lastly about the rebels’ texts, in regard to the Aristotelian Triad of rhetoric appeals, it is feasible to point out a frequent appeal to Pathos as a persuasion technique. As often occurs in “humanitarian” writings, the rebel factions attempt to assign blame to the UN for the ongoing bloodshed in the war, using this sort of emotional blackmail as a means to get them to support their regime change aspirations, presented as the only solution. This can be identified in the following excerpt:

“The Security Council – which is responsible legally, politically, and morally to preserve world peace – has failed to defend the Syrian people, contribute in achieving their noble goals, and prevent the occurrence of massacres carried out against them. This is while we see attempts to rehabilitate the regime, even serious endeavors to make it a part of the present and future of Syria. We also see the Security Council ignoring the terrifying massacres that occurred and continue to occur before and after the presidential statement. The national forces who signed this document reafirm their adherence to the fixed principles of the Syrian people in their glorious revolution and consider that any transgression against these principles to be negligence towards the rights of the Syrians, disdain of their blood and sacrifice, and an effort that will never succeed, because it assumes and enforces a foundation that is rejected legally, politically, and morally.” (second document, last paragraph)

On the above passage, one can notice 1) an emotional appeal to humanitarian sensibilities, which are exploited in order to achieve 2) a political goal (the immediate overthrow of Assad), which is presented not only as the only means available to end the Syrian carnage, but also as the will of the “Syrian people”, once again displaying 3) a craving for legitimation based on the popular authority, notwithstanding the absence of any evidence whatsoever for this overwhelming popular support they claim to have.

Regarding the comments of the Islamic State, it should be stated that, being an extremist jihadi-salafi organisation, they claim to represent the only pure form of Islam in the world, a position which unloads them of the burdensome need to make specific concessions in their speech; there isn’t any international entity (as the UN and the US are for the rebels) they are explicitly trying to please or gain support from. The source of their power of persuasion seems to lie precisely in an air of self-sufficient absoluteness, which allows them to speak as if they were the direct spokesmen of the will of God on earth and which has been shown to be extremely seductive as to attract young jihadists and suicide bombers from around the world. Their pronouncements have no mincing words, making the job of a discourse analyst in some sense much easier — there are no hidden messages, nor underlined or implicit insinuations to be unveiled; everything is said clear, straightforward and loud as a textual caricature.

In an attempt to map their discourse, lexicalisation and wording is what most strikingly catches the eye, as the reader will quickly note that ISIS barely ever refers to other subjects by their actual names at all, rather preferring to use specific adjectives, attached features or Arabic words. The entire Western and Christian world is referred to as “the crusaders”, as for instance in “does a ‘jihad’ group hand over its posts to crusader agents backed by crusader jets to fight against Muslims?” (p. 11). This exemplifies a recurrent IS attempt to employ a pre-modern vocabulary, aiming to present their present-day conflicts as bound to the reality prevalent at the time of the Islamic sacred and historical writings; this lexical usage dividing the world into “crusaders versus mujahidin”, “idolaters versus believers”, as if it was an unceasing sacred epic battle, is most certainly another appealing factor for youngsters worldwide who may find less heroic or exciting the monotony of their comfortable and disenchanted modern life.

Other lexicalisation choices include: “nationalists” and “democrats” for the rebels, “sahwat” for most of their opposition in Syria, “nusayri” (“alawite”) for Bashar al-Assad, “rafidah” (“rejectors”) for most of Assad’s Shia allies, and so forth.

The legitimation is extracted from both moral evaluation and divine authority, as they claim to be the only state to purely represent Allah’s will and implement his Shari’ah law in proper form. This gives them the legitimacy to treat all other Muslims as infidels, often pronouncing takfir upon them.

Interpretation, time and place, processing analysis

To begin a proper contextualization in the Syrian political situation, we should firstly stick to the process of production, reception and the expectations at play. As noted, a remarkable distinction between the Islamic State and the rebels is that the latter are addressing a specific public in order to attain a short-term goal, namely, the fall of the Assad regime and all of its “pillars”, as is repeated to exhaustion in their documents. There is this political interest, and, as a means to achieve it, the interested parties need the UN, as a major institution with a power to interfere in international affairs far beyond their own at their local level. Wherefore, to be able to get the UN support, it is necessary for the rebels to comprehend the way they think in order to be able to reproduce their humanitarian, democratic and secular discourse thereby gaining the Western world’s trust.

This Machiavellian, realpolitik interpretation is based partially in passages from the rebels’ texts, but also in some historical data. In the last paragraph of the second document, Assad’s departure is presented as the “major issue” under discussion. Though expressing in other passages the necessity of creating a stable Syria based on the will of the Syrian population, they at any moment take into account the possible scenario of Assad’s permanence being a better choice to maintain stability and harmony for that country. Even now, that even the UN and the US have dropped the demand for Assad’s stepping down, the Syrian opposition factions keep repeating the same “Assad must go, dead or alive” chorus. Not evenfighting ISIS seems to be regarded a higher priority for the moment than the destruction of the regime, if we consider that producing a vacuum of power in the country at this point might not be the best way to prevent the advance of IS armies. A quick look at what is Lybia today after the overthrowing of former leader Muammar al-Gaddafi may give us a glimpse of the importance of this point: still facing civil war, with IS occupation of large areas, a complete disaster. Is this genuinely defending the country’s stability, or just pursuing a political interest?

In regard to their appeal to the will of the Syrian people, it is very relevant to note that since the beginning of the Syrian crisis, in 2011, this overwhelming popular support for the “Syrian Revolutionaries” has been far from evident. The third clause of the third document refers to a “popular outrage” for the “murderous regime” and its allies Russia and Iran. The following clause states that, for a number of reasons, Bashar al-Assad has been left “with no credibility or confidence”. However, a quick search on the Internet brings us to official polls conducted by Western countries (such as the US and Britain) showing that both Assad and his key ally Iran enjoy much larger support in Syrian ground than the opposition itself.2 A similar situation was to be found in the beginning of the conflict as well, before the demographic disaster of the Syrian civil war.3 Still, according to the rebels’ discourse, there is no conceivable future for Syria with Assad in it.

Thus, once again we may ask, is this genuinely about defending the will of the Syrian population, or is it about attaining short-term political interests leaned on the humanitarian, globalist discourse dominant in the West?

Another dimension of the discursive strategy of persuasion promoted by the rebel factions to the UN utilises the Aristotelian category of Ethos: in order to attract credibility to their image, they seem to try as much as possible to distance themselves from the armed conflict. The Syrian war has long ago reached a point in which none of the groups involved can claim not to have shed any innocent blood, or not to have formed any skewed alliances in the battleground. Nonetheless, despite being armed groups not so unlike the others, the Free Syrian Army et. al. write as if they were clean-handed diplomats, to the level of denouncing its political opponents as “red-handed with the blood of the Syrians” (clause seven, first document, in reference to Iran), as if anyone wasn’t to some extent.

Turning again on ISIS: it is worthy of note, funnily enough, that in their broad undertaking of recruitment of Jihadists around the world, it would be a mistake to claim that its target-audience is necessarily or even mainly the global Muslim community. The Islamic State cares not about Islam and its worldwide manifestations (Shia, Sufi, Alawite); it cares only about its own message, which, extreme as it is, attracts extremist observers from the most different religious and cultural backgrounds. It is symptomatic, in this sense, that IS should state (in a passage I quoted earlier) precisely that "the muhajir is a Muslim even if he had been a Christian American before his Islam".

Socio-historical conditions

There is a main point I want to defend as to insert the analysed discourses into a broader historical and social perspective.

It begins with asserting that the overall experience of the so-called Arab Spring, as has been shown in Libya and Egypt, served to confirm that the Middle East does not share the mental climate needed to produce parliamentary democracies in the lines of those of Europe or of the US. Nor will they necessarily ever do; different peoples, different political sensibilities. They have shown that groups once thought to be representatives of massive liberalisations inside the North-African and Levantine collective minds, glorified by the entire Western world as the "freedom-fighters", would later struggle to put their discourse into practice and get public support, or then would in some cases prove to be little more than "terrorists with a human face".

The point is that, by financing and supporting those rebel groups, the West has opened a field for the creation of what we may call "Arab Spring rhetorics", in which these values of freedom and democracy are turned into a form of currency; the West has taught groups of the most diverse ideological leanings that if they use the right magic words, in the day after there will be weapons and money in their hands, no matter if their actions actually produce any significant move towards democratisation. This foreign policy is naïve, if not evil-minded; it allows for and reproduces empty speeches such as those analysed throughout this paper, which prioritize pretty words over crude facts. This is a factor which helps produce this field of open negotiations in which words such as "democracy", "foreign intervention" and "terrorism" are turned into mere weapons, and in which ambiguous discourses reign supreme over the plain critical look.

Notes:

1. Every issue of the magazine opens with the following quote by scholar Abu Mus’ab al-Zarqawi: “The spark has been lit here in Iraq, and its heat will continue to intensify –by Allah’s permission- until it burns the crusader armies in Dabiq”.

2. <http://www.globalresearch.ca/bashar-al-assad-has-more-popular-support-than-the-western-backed-opposition-poll/5495643> Accessed in: 11 April 2016, 05:48

3. <http://www.theguardian.com/commentisfree/2012/jan/17/syrians-support-assad-western-propaganda> Accessed in: 11 April 2016, 05:52

Reference list:

BUNZEL, C. (2015) From Paper State to Caliphate: The Ideology of the Islamic State. (Brookings) Available at: <http://www.brookings.edu/~/media/research/files/papers/2015/03/ideology-of-islamic-state-bunzel/the-ideology-of-the-islamic-state.pdf> Accessed in: 11th of April 2016

FAIRCLOUGH, N. (1989) Language and Power (London, Longman)

JANKS, H. (1997) Critical Discourse Analysis as a Research Tool , Discourse: Studies in the Cultural Politics of Education, 18:3, 329-342

, Discourse: Studies in the Cultural Politics of Education, 18:3, 329-342

DABIQ Magazine, 12th edition, Just Terror, available for download at: <https://www.clarionproject.org/news/islamic-state-isis-isil-propaganda-magazine-dabiq> Accessed in: 11th of April 2016, 6:57

English: Bashar al-Assad - ARD-Interview

<https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=8_E5lvdDtEI> Accessed in: 11th of April 2016, 6:58