The Africa Question

28.12.2012

With the impending handover of the chairmanship of BRICS by India to South Africa, there is a flurry of activities in BRICS capitals, including a visit of a high-powered South African delegation to New Delhi. While there would be discussions on the modalities of the handover, the central focus must remain on the BRICS agenda.

If recent conversations with South African scholars are any indication, the country’s chairmanship of BRICS may be conditioned by a strong impulse to represent Africa. In two recent conferences in China, interventions by South African delegates on BRICS matters introduced a heavy dose of Africa, issues that currently engage the African Union and the state of the continent generally. In the run up to the 2013 BRICS summit, the country seems to be placing upon itself the onerous task of discovering and representing a unified African voice. While this has drawn criticism, it is also flawed in more ways than one and has the potential of undermining the progress so far.

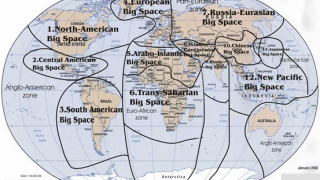

The first problem is the inherent moral hazard. South Africa must not see its role as the voice of Africa at BRICS. It would be presumptuous and a number of African countries may take strong exception. And is it anyone’s case that it is only Africa that somehow needs a special relationship with BRICS? Home to half of the world’s poverty and any number of development and social challenges, South Asia may deserve such attention as well. Should India then be the voice of South Asia and represent the subcontinent? Surely, some South Asian countries would have a reason to challenge this. This can also be argued in the case of Brazil and South America, Russia and Eurasia, China and East Asia. Such ambassadorial roleplay for larger regions is dangerous and can weigh down the lithe and nimble platform that BRICS seeks to be.

On the other hand, almost every BRICS member has robust bilateral engagements with the continent. While the Chinese may be more recent partners to many African nations, India has both civilisational and contemporary ties. Many Indians are settled in Africa; India has maintained among the largest peacekeeping forces; and of course Indian businesses, much like their Chinese counterparts, are taking increasing interest in the continent. Brazil also has a fair constituency in Lusophone Africa. Africa’s immense resource wealth, and underdeveloped infrastructure, have attracted a large amount of commercial interest from Brazil. Hence, can the premise that South Africa represents Africa and is best positioned to serve its interests pass muster?

The second flaw with the “South Africa for Africa” formulation is that it misunderstands the reason for South Africa’s inclusion in the group. Only a rather naive (and linear) rationale will attach the responsibility for Africa to South Africa. While it is undeniable that one of the key reasons for the inclusion was to have a voice from the continent, the voice was meant to speak for itself alone. South Africa is an emerging economy that offers a unique perspective and adds value to BRICS by itself. It is counterproductive and self-defeating for a small club to allow proxy memberships.

The third and central weakness of this proposition is its lack of appreciation of the core BRICS objectives. It is indisputable that the purpose of this group is to offer a counter-narrative on global governance to the one scripted by the incumbents in the Western hemisphere. BRICS is not and must not become another “trade union” or voice of the “global opposition”. It is a club that allows these five nations to pitch their collective weight behind efforts to shape and change rules for the road, old and new, at the global high table. There is a lot at stake. The world is in flux and governance is being re-imagined, redefined and indeed renegotiated. BRICS allows each country an exponentially weightier presence while parleying with the incumbents. That must remain the group’s salience.

It is time for BRICS to ask themselves some blunt questions. Should the resources and time devoted by each country at this forum be invested in regional issues such as those important to Africa? Should the tensions and imperatives of South Asia find centrestage? Will it be in the interests of BRICS to be engaged with the problems of the South China Sea? Or should BRICS remain that unique proposition, where a group of emerging economies, with critical stake in the global future, create a platform for meaningfully engaging with the developed and developing countries on key issues?

There is no denying that South Africa will remain the continent’s economic powerhouse for the foreseeable future. It is also a veritable geographic fulcrum, which is viewed by some as a strategic node between Latin America and Asia. This gives South Africa a weight far greater than its military might or economic numbers. South Africa by itself completes BRICS. As the next summit draws closer, it must urgently conduct a strategic and realist re-evaluation of what it wants from BRICS against what is on offer.

Source: BRICS Forum