The 10th Anniversary Of The Arab Spring

18 December 2010 is considered to be the starting point of the riots, unrest and uprisings in the Middle East and North Africa collectively referred to as the Arab Spring. The day before, a young fruit seller by the name of Mohamed Bouazizi set himself alight in the Tunisian town of Menzel Bouzaiane. His actions were in response to his humiliation at the hands of the police, and they sparked rioting and widespread protests. On 14 January 2011, Tunisian President Zine El Abidine Ben Ali fled to Saudi Arabia, and a military-controlled transition period was declared in Tunisia, where the events themselves were referred to as a second Jasmine Revolution. The revolution was not without its victims. According to the UN, 219 people died in the country and 510 were injured.

In late December 2010, neighbouring Algeria was the first country to be rocked by mass demonstrations in a chain reaction of Arab Springs. The country was saved relatively easily, with the president declaring that the state of emergency would be lifted.

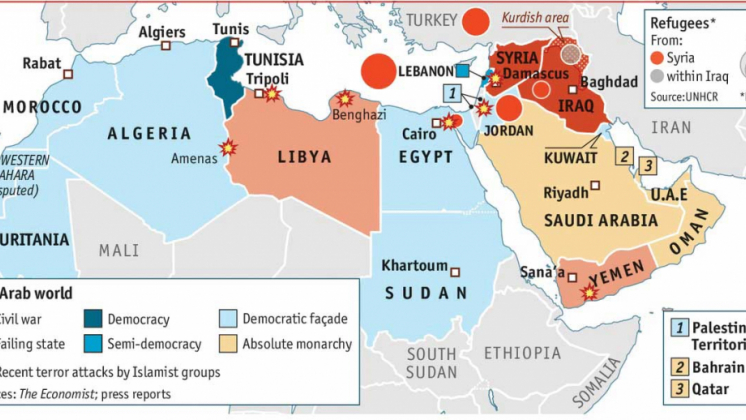

From January 2011, more and more countries were gripped by protests. In some cases, they were quickly localised and brought to an end, in others there were demands for reform, and in yet others the protests were brutally suppressed. In countries such as Libya, Syria and Yemen, the protests are still going on.

It is telling that acts of self-immolation were also committed in Mauritania, Saudi Arabia and Morocco, but these countries’ dictators were able to cling to power and even help suppress coup attempts in neighbouring countries, such as when Saudi Arabia sent troops to Bahrain.

Djibouti, Somalia, Kuwait, Western Sahara, Oman and Jordan were the least affected, although Jordan saw an influx of Syrian refugees and the Sultan of Oman transferred some of his power to parliament.

The protests in Iraq and Lebanon are difficult to separate from the lengthy crisis and conflicts that were already ongoing in these countries. Yet in terms of Washington’s reformatting of the Greater Middle East, the deteriorating situation in these countries was directly related to the interests of the US and Israel. In fact, protests have flared up time and again in Iraq and Lebanon. The most recent riots took place in December 2020 in Iraqi Kurdistan over the non-payment of salaries to civil servants.

On the back of the Arab Spring in Sudan, South Sudan declared independence following a referendum in 2011, and the country was immediately recognised by Western observers and even accepted as a new member state of the United Nations. The oil-rich region proved to be landlocked, however, which sparked a conflict after a while between the two halves of this once united country.

Libya is a difficult case, since the intervention of the US and NATO, and the later creation of a UN-sanctioned “no-fly zone” over the country, spelled the imminent military defeat of Colonel Gaddafi’s government, which happened a while later. But subsequent events exposed the fallacy of the strategy being relied on by the West.

It should be mentioned that US and transnational foundations to promote democracy were operating in many of the countries where the Arab Spring began. Their activists, who had been trained years before, were at the epicentre of events and passed on colour revolution techniques to the local population that they had developed in the Commonwealth of Independent States and the Balkans.

Arab Spring in Algeria

There was also some interference from “international” financial organisations. In 2011, for example, the international rating agency Moody’s downgraded Egypt’s government bond rating, and the outlook was downgraded from “stable” to “negative”.

According to the IMF, the Arab Spring caused losses of $55 billion at the end of 2011. Given the fall in GDP and the budget cuts of the countries affected, this figure increased significantly in the years that followed. Yemen, Syria, Iraq and Libya suffered the biggest losses.

But the attempt to reshape the region and impose standards of Western democracy on it has failed. This is evident in Egypt, where the military has not only taken complete control, but also imprisoned the short-lived president Mohamed Morsi, a member of the Muslim Brotherhood; sentenced to death many of the activists involved in the overthrow of President Mubarak; and tightened a number of laws.

According to the Council on Foreign Relations, the democratisation of society was only achieved in Tunisia, although the country has also seen a rise in unemployment. In all the other countries affected by the Arab Spring, the situation has only worsened. As a consequence, the goals that Western politicians and experts talked about, as well as their partners and agents in Arab countries, have not been achieved. Living standards have also fallen in Libya, Syria and Yemen. There are now more than 17 million refugees and internally displaced persons, with the largest numbers being recorded in Syria and Yemen.

It is important to note that it was thanks to the Arab Spring that the emergence of ISIS was made possible in 2013. Extremists initially tried to use the situation to their advantage. The radical wing of the Muslim Brotherhood did this in Egypt and Libya, while also freeing their fellow believers from prison. In September 2011, al-Qaeda leader Ayman al-Zawahiri stated: “We are on the side of the Arab Spring, which will bring with it true Islam”.

While the US was interested in the region’s democratic transformation in order to extract dividends at some point in the future (the Arab Spring began under the administration of Barack Obama), a number of neighbouring countries benefited directly from what was happening. Although Turkey was also rocked by protests during this period (they began in Istanbul’s Taksim Square in 2013) and saw an attempted uprising in 2016, the country occupied northern Syria. Turkey has also consistently defended its interests in Libya, signing a maritime boundary agreement with the Government of National Accord that will provide it access to hydrocarbon deposits. Turkey’s ambitions in the Eastern Mediterranean resulted in strained relations with EU member states, primarily France and Greece, in 2020.

A man stands atop a building looking at the destroyed Syrian town of Kobane, also known as Ain al-Arab, 2015

The lessons of the Arab Spring are important for understanding the real interests of the US and the West. It was only Russia’s military presence in Syria that helped prevent a Libya-style collapse in the country and defeat ISIS.

Israel also took advantage of the situation. As well as the country’s regular interference in Syria (in the form of air strikes) and its attempts to influence the situation in Lebanon (by putting pressure on European countries, with America’s help, to recognise Hezbollah as a terrorist organisation), Israel has partially managed to breach the Arab blockade.

According to Israel’s former prime minister, Shlomo Ben-Ami, the geopolitical terrain in the Arab world will continue to shift in 2021. This will partially be to do with the Abraham Accords – the establishment of diplomatic ties mediated by the US between Israel on the one hand and Bahrain, the UAE, Morocco and Sudan on the other. Ben-Ami believes that as soon as Saudi Arabia follows suit, the Arab–Israeli conflict will work itself out, although the Palestinian issue will remain unresolved.

The Biden administration will probably continue the Democrats’ traditional policy and try to influence the political processes in the Middle East and North Africa. But Washington’s actions will be complicated by the ongoing conflicts in Libya and Yemen, the presence of terrorist cells in Syria and Iraq, and the intransigence of Turkey, which, following the introduction of sanctions by the US, will try to retaliate.

Ten years have passed, but the Arab Spring is still not over.