Friedrich Ratzel: The State as a Physical Organism

Foundations of geopolitics

1.1 Background: The German “Organic School”

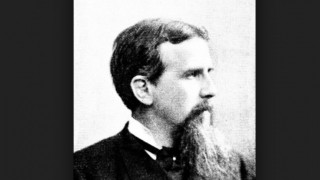

Friedrich Ratzel (1844-1904) can be considered “the father” of geopolitics,

although he did not use this term in his own writings. He wrote on “political geography.” His principal work, published in 1897, was titled “Politische Geographie.”

Ratzel graduated from Karlsruhe Polytechnic University where he attended courses in geology, paleontology, and zoology. He completed his education at Heidelberg, where he became an acolyte of Professor Ernest Haeckel (who was the first to use the term “ecology’). Ratzel’s ideology was grounded in evolution and Darwinism and colored by his pronounced interest in Biology.

Ratzel participated in the Franco-Prussian War, where he served as a volunteer and received the Iron Cross for bravery. In politics, he gradually became a committed nationalist and in 1890 he joined the “Pan-German League” of Karl Peters. His lengthy travels in America and Europe added to his own scientific interest in Ethnological research. He became a lecture of geography at the Munich Technical Institute and in 1886 he moved to a similar position in Leipzig.

In 1876 Ratzel defended his dissertation “The Chinese Immigration,” and in Stuttgart, he came out with his fundamental work in 1882, “Anthro-Geography” (“Anthropogeographie”) in which he formulates his basic idea: That there is a connection between the evolution of peoples and demographics with physical geographic data; the influence that physical terrain has on a people’s culture, political development, and so on.

But his most fundamental book was “Political Geography.” 1.2 The State as a Living Organism

Ratzel showed in his work that land is a fundamental, fixed constant around which the interests of a people rotate. The movement of history is predetermined by earth and territories. Further followed by an evolutionary inference that the “state constitutes a living organism,” but one that is “rooted in the ground.” The state develops based on its territorial topography, size and its comprehension by the people. Thus, the state reflects the objective geographic principle and subjective national comprehension of this principle, and this is expressed politically. Ratzel considered a “normal” state, one which most organically combined geography, demographics, and ethnological national parameters.

He writes:

The state in all stages in its development as an organism contends with the necessity of preserving its connection with the terrain and therefore they should be studied from a geographical point of view. As shown in ethnology and history, a state develops on a spatial basis--conjugating and merging more and more--and extracting from it more and more energy. Thus, a state turns out to consist spatially, maintained and animated by this space, and should be managed, described, and measured through geography. A state is described in a series of phenomena, with the expansionary principle being the most prominent. (Political Geography 1)

It is clearly visible that from such an organic approach, Ratzel understood territorial expansion to be a natural, living process, similar to the growth of living organisms.

Ratzel’s “organic” approach is in relation to its space (Raum). This “space” brings over a cardinal material category in a new quality, becoming the “Living Sphere,” “Living Space” (Lebensraum), in a “Geobioylogical Environment.” From this concept arises two different, important terms of Ratzel’s: “Sense of Space” (Raumsinn) and “Living Energy (Lebensenergie). These terms are closely related to each other and denote some special quality, inherent in geographical systems and predetermining political figuration in the history of the people and state.

All these theses comprise the fundamental principles of geopolitics, in that form, which would be developed somewhat later by followers of Ratzel. Furthermore, the relationship to the state is similar to a “living, physical organism, rooted in the soil;” this is the chief principle and axis of geopolitical methodologies. That approach is oriented in synthetic analysis of the entire complex of phenomena, regardless of whether they belong to the human sphere or non-human sphere. The land is a concrete expression of nature, the surrounding environment, and is not regarded as a continuous living body of the ethnos--it is the land being inhabited. The material structure itself dictates the proportions of the final cultural products. In this idea Ratzel is the founder of the entire German School of “organic” sociology, of which Ferdinand Tönnies is the most notable representative.

1.3 Raum - Political Organization of the Land

Ratzel’s observation was that there is a correlation between ethnos and space--as seen in the following excerpt from “Political Geography:”

The state develops like an organism, tethered to certain parts of the earth’s surface, and its characteristics developing from the characteristics of the people and land. The most important characteristics are its size, location, and borders. Followed by types of soil, along with vegetation levels, irrigation, and finally, correlates in relation to the rest of the conglomerations of the earth’s surface, and in the first place, with neighboring seas and uninhabited lands, which, at first glance, does not represent especial political interest. The aggregate of these characteristics constitutes the Land (das Land). But adding to this, when speaking about ‘our country,’ is that created by man--memories connected to the earth. So, an initially pure understanding of geography transformed into the spiritual and emotional bonds of the inhabitants of a land and their history.

A nation is an organism not only because it articulates the lives of the people in fixed soil, but due to its intertwining bond, becoming something unified--unthinkable without one of two components. Desolate land, incapable of nurturing government, are barren fields in history. On the contrary, habitable land promotes state development--particularly if the state is surrounded by natural boundaries. People may feel themselves to be natural in their territory, but they are actually constantly mimicking one and the same characteristics, which proceeding forth from the terrain, will be inscribed in it. (2)

1.4 The Law of Expansion

The relationship of the state to a living organism implies the refusal of the

concept of “borderlessness.” The state is born, grows, and dies like a living being. Consequently, a state’s spatial expansion and contraction are natural processes connected to an intrinsic life cycle. Ratzel, in his book “On the Law of Spatial

Growth of the State” (1901), laid out the seven laws of expansion: 139

1. The state expands in relation to the development of its culture

2. The physical growth of the state is accompanied by other manifestations of its

development: in the spheres of ideology, production, commercial activities, and

a mighty, attractive proselytizing power.

3. The state expands by consuming and absorbing units of lesser political

significance.

4. The border is an organ located on the state’s periphery (understood as in an

organism).

5. Carrying out its territorial expansion, the state strives to cover important

regions for its development: coastlines, river basins, valleys, and in general, the

richest territories.

6. The initial impulse for expansions comes from outside—that is in its expansion

the state provokes states (or territories) with clearly inferior civilizations.

7. The general tendencies of assimilation or absorption the weakest nations are

reinforced by an even greater increase in self-perpetuating momentum.

Unsurprisingly, many critics have rebuked Ratzel for his writings because they

have been a “catechism for imperialists.” While he himself by no means pressed for the favorite methods for justifying German imperialism, still he did not disguise that he had nationalist convictions. For him, it was important to establish a conceptual instrument for advocating awareness of the history of the state and nation and their relationship to the land. In practice, he sought the awakening of

“Raumsinn” (“the spirit of the land), among the leaders of Germany, whom regarded geopolitics as a dry academic discipline merely representing abstraction. 1.5 Weltmacht and the Sea

Ratzel was greatly influenced by his experiences in North America, which he studied thoroughly and published two books on: “Maps of the Cities and Civilizations of the American South” (1874), and “the Southern United States of America,” (1878 1880). He noted, having his considerable experience of political geography in European history, the far greater degree that the “spirit of the land” had in American expansion because Americans first had the task of mastering the “empty” expanses. Accordingly, the American people sensibly put into practice what the Old World had come to intuitively and gradually. So, in Ratzel’s work we come across the first formulation of another important geopolitical concept— “world power” (weltmacht). Ratzel observed that large countries have a tendency in their development to maximize geographical expansion, gradually moving to the global level.

Therefore, some time or another, geographical growth should arrive at its continental phase.

Applying this principle—inferred and deduced from the American political experiment and strategical unification of the continent’s space—to Germany, Ratzel predicted its destiny to be a continental power.

He also anticipated another important geopolitical topic—the importance of the seas for civilizational development. In his book “The Seas: The Source of 141

Nations’ Power” (1900) (4), he pointed out the particular necessity of each mighty power to develop its naval forces, especially because full-fledged global expansion requires it. That some nations and states brought this about spontaneously (England, Spain, Holland, etc.), land powers (Ratzel, naturally, had Germany in mind) should do this sensibly: develop a fleet that is necessary under the conditions for approximating the status of a “world power.”

The sea and “world power” were already connected for Ratzel, although only later geopoliticians (Mahan, Mackinder, Haushofer, and especially Schmitt) gave this topic completeness and centrality. The works of Ratzel are the essential for all geopolitical research. In a compressed form, his works contain practically every basic thesis, which would form the basis of this science. Kjellen, a Swede, and Haushofer, a German, based their concepts on Ratzel’s works. His ideas were also taken into account by Frenchman Vidal de la Blache, the Englishman Mackinder, Mahan, an American, and the Russian Eurasianists (P. Savitsky, L. Gumilev, etc.).

It should be noted that Ratzel’s political sympathies were not accidental. Practically all geopolitics has been brightly marked by nationalist sentiment, regardless of whether it wears the cloak of “democratic” geopolitics (Anglo-Saxon geopolitics of Mackinder and Mahan) or “ideological” forms (Haushofer, Schmitt, and the Eurasianists).