David Engels: The decline of the West is not a shipwreck, but like the slow setting of the sun

While tracing the path of conservative revolutionism, it would be impossible not to mention Oswald Spengler, one of the cornerstones of this movement. Spengler’s understanding of history and his predictions about civilizations are still debated today. This interview with world-renowned Spengler expert David Engels is an introduction for readers who want to better understand Spengler’s ideas and their impact on today’s world. In the last two years, important works by Oswald Spengler such as Man and Technique and The Decline of the West have been published in Turkey by different publishing houses. However, his other important works such as The Hour of Decision, Prussianism and Socialism and Address to German Youth have not yet been translated and are waiting to be discussed.

What period did Spengler live in and what made him a ‘conservative revolutionary’?

Spengler was a typical child of the German 19th century with its encyclopaedic interest for past civilisations, its openness to technology and its fascination for the construction of huge philosophical and historical “systems”. However, Spengler’s main period of activity falls into the Republic of Weimar, which saw the abrupt and traumatic deconstruction of the “old world” of the pre-war period. Spengler’s endeavour to show the inevitability of the decline and fossilisation of all high civilisations, the West included, fell thus on fertile grounds and helped many people to make sense of what was happening, though very often, the readers narrowed down Spengler’s huge historical vistas to some very short-term elements and overlooked that, for Spengler, the slow decline of the West was a long procedure that would only culminate in the late 21st century.

Spengler is indeed often considered as “conservative revolutionary”, but I doubt whether he was really that “conservative” and “revolutionary”. Indeed, as a historical determinist, he was convinced the West was about to enter a time when liberal democracy would first transform into financial oligarchy and then be supplanted by Caesarism, civil war and imperial unification. Consequently, he considered Cecil Rhodes and Mussolini as first symptoms of an evolution that would only culminate, following to him, in the 21st century, and hoped that Germany would shake off the Weimar Republic and enter into the competition for the construction of a future pan-European Empire, though he loathed the National-Socialist sand soon entered in collision with Hitler and his party because of their racial doctrine which he could not endorse, being convinced about the equality of all high civilisations. This is also why I am not sure whether Spengler really was a “conservative”, as he was convinced that the fading away of the old world was an inevitability one had to accept, albeit grudgingly, in order to endorse technology, imperialism and modernity.

The first work that comes to mind when Spengler is mentioned is The Decline of the West. What did he want to tell in this work? Did the West really collapse, or is this process still going on?

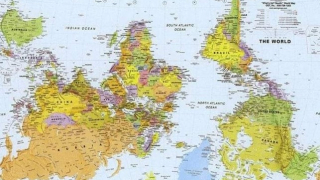

The title “The Decline of the West” guaranteed Spengler’s lasting success, but was (and still is) the reason for many misunderstandings. Spengler’s main thesis is the idea that all high civilisations – Egypt, Mesopotamia, China, India, Classical Antiquity, Mesoamerica, the monotheistic Near East, the West and probably also Russia – are not only equal to each other, but also evolve through rigorously parallel stages, corresponding to the developmental phases of an organic being. This general idea was not absolutely new, of course, but Spengler was the first who tried to play this hypothesis systematically through based on modern historical research.

Also, Spengler wanted to show that the modern West had reached its final stage of development and was about to enter a period corresponding in general to the late Roman Republic which he saw as the closing moment of Classical Antiquity before the Principate of Augustus ushered in its final fossilisation and petrification. This idea was not absolutely new either, as since the 19th century, most European intellectuals were influenced by an atmosphere of “fin de siècle”, but Spengler gave a much broader historical sense to this impression. However, by choosing the title “Untergang” (literally “Sinking”, not “Decline”), he contributed to a certain misunderstanding of his work, as this word does not only refer, in the German language, to a “shipwreck” and thus a spectacular catastrophe, but also to the slow setting of the sun. Spengler later explained that it was the latter sense he endorsed and that he could also have chosen the “Fulfilment of the West” as an adequate title for his work, but of course, the more spectacular interpretation of “Untergang” as some form of “collapse” was the one the general public retained – until today. This is also why this process is, of course, still going on and will be continuing for some generations, as Spengler has clearly shown in his work that the final stage of an “Augustan” European empire will only be reached in the 21st century, while the Civilisation-state emerging from this transition will potentially endure for a couple of centuries more, exactly as the Roman Empire, the Han Empire or the Ramesside Empire survived for quite some time, though in an ever more primitive and petrified way.

What kind of predictions does Spengler’s cyclical understanding of history offer about the future major changes in world politics? What kind of a global order might emerge after the collapse of Western civilisation?

First, let me insist that Spengler’s historical thought is not strictly speaking “cyclical”, as the end of a civilisation is never ever followed by its rebirth: its death is final. Of course, there might be new civilisations arising later, but rarely on the same territory, and generally only many centuries later and based on totally different mental paradigms. So these civilisations are monads, not elements of a chain.

As to the future, the impending establishment of a Western civilisation empire would probably see a certain return of Western imperialism and self-assertion, as the post-liberal universalism and nation-state centered diplomacy so typical for the 20th century would be replaced by some form of civilisational patriotism. We would thus enter a stage of coexistence between several civilisation-states competing with each other for dominance over their respective fringes and strategic resources, but accepting, broadly speaking, their mutual limitations, exactly as the Roman Empire ceased to expand after Augustus, coexisted rather peacefully with the Iranian civilisation-state and preferred defence to attack. Nevertheless, the West would slowly fossilise and lose its resilience, technological progress would also slow down, and the Western world would start to resemble China and Japan in the 18th century: a society largely closed on itself and ever more immobile. Thus, the West would become the youngest civilisation state, as China, Japan and India, but also the fragmented Muslim world have reached this stage already many centuries ago and only derive their present energy from the impulse of the West.

Amidst these fossilising remnants of previous civilisation, two new cultural spaces will probably emerge. On the one hand, Russia: Spengler was convinced, as I am by now too, that Russia is not a part of the Western world, but a high civilisation on its own, though it is probably still in a period of gestation and needs to free itself from the overwhelming influence of the West in order to launch its own civilisational cycle. On the other hand, I personally believe that in a couple of centuries or so, Africa could become the homeland of a new, future civilisation, though this is of course very speculative.

How does Spengler’s concept of ‘Prussian Socialism’ transcend the traditional right-left divide? How can this concept be evaluated today?

Spengler believed that, in the 20th century, the previous main bearers of the Western civilisation, France, Spain and to a certain extent Italy, had ceased to be active forces, and that only Germany as well as the Anglo-Saxon sphere remained as the last agents competing for the shaping of the future European civilisation state. In his view, the Anglo-Saxon world represented the principle of liberalism, while Germany, led by Prussia, stood for the principle of hierarchical collectivism, corresponding broadly speaking to the opposition between Carthage and Rome during the 3rd and 2nd century BC. Personally, I am not so sure about this kind of dualist simplification, but if we accept it on a working basis, we could speculate that the Anglo-Saxon principle superseded the Prussian one during the Second World War, but that the modern European Union, increasingly dominated by Germany and a certain bureaucratic ideal and a Kantian universalism, is transforming into something that Spengler may have recognised as “Prussian” (at least in its 18th century “enlightened” version), though it is (for the moment) devoid of any form of patriotism or militarism.

In his criticism of modernity, Spengler saw technology as an element of the dissolution of cultures. How do you interpret these criticisms of Spengler in today’s digital world?

For Spengler, technology is not an element of dissolution, it is rather a symptom of the late phase of each civilisation. Indeed, the Hellenistic World in Classical Antiquity, the Warring States in China, the Abbasid caliphate in the Oriental world, and of course the West during the 19th and 20th century, all of these are characterised by an exponential scientific progress that corresponds to a phase of imperialist and colonialist expansion, the spread of materialism and the advent of a purely expressionist and theatrical art. Hence, progress is not the reason of “decline” (or “fulfilment”, as we said above), but just one amidst many other symptoms. The 21st century is undoubtedly, as foreseen by Spengler, the summit of this progress, and will probably also be it end.

This may seem somewhat surprising, as we all have been accustomed to think about technological progress as some form of linear, never-ending and exponential evolution, but if we compare the West to the other civilisations, then we should expect that, during the next generation, no real scientific paradigm shifts are to be expected, and that apart from some further application techniques, “progress” as we know it now, will largely stop. And if we look back into our recent past, the technological jump that separates the early 19th from the early 20th century is indeed much bigger than the one separating the latter from the 21st century. Furthermore, many technologies are already being deconstructed before our eyes, especially in Europe: maglev trains like the Transrapid, ultrasonic passenger airplanes like the Concorde, transportation technology like hovercrafts, even combustion engines and nuclear energy – all these are abandoned or their use consciously refused before our very eyes, while anti-scientific absurdities such as Gender studies, climate apocalypticism or post-colonial self-deconstruction are massively pushed by the elites. It is only a matter of time before this anti-technical attitude reaches the US which is in so many ways the “last Faustian nation”.

At the opening ceremony of the Paris Olympics, we saw the dominance of the world system by those who disregard the sacred and dominate world politics. Gender roles are discussed, people are enslaved by technology and interest. Do you think the West has any values left to hold on to?

Many of the ideological absurdities of modernity were indeed foreseen by Spengler, especially ecologism, Western oikophobia, cowardly pacifism and the self-sabotaging of the sciences, but I am convinced that Spengler would be shocked if he saw the extent of self-destruction that is underway today. Nevertheless, for Spengler, the question of “values” is a purely aesthetic one: As Spengler was, broadly speaking, an atheist and saw moral and philosophical systems as purely relativist symptoms of the growth and decline of civilisations, he certainly deplored the decline of traditional values as proof of the decline of the West, but he had no conceptual grounds from which to condemn them from an absolute point of view, except of course their purely pragmatic utility in keeping a society together. This is where I myself differ from Spengler, as I believe in a perennialist and transcendent truth that is beyond all civilisations and which expresses itself not only through the human intellect, but also through natural law, and which consequently legitimates a certain set of absolute moral standards whose perversion is thus not only a mere historical fact among many others, but also a concrete deviation from absolute values, though of course, this deviation takes different forms for every late civilisation.

Can a ‘neo-Spenglerist’ perspective be developed today that reinterprets Spengler’s thoughts? Is it possible to make a new reading of the contemporary Western world based on Spengler’s works?

Absolutely: This is what I am doing for at least 20 years by now, focussing mainly on two aspects. On the one hand, Spengler’s historical knowledge was broad, but nevertheless often dilettante and moreover conditioned by the limits of early 20th century historiography. In the meantime, we know much more about civilisations which Spengler treated only in a very marginal way or even ignored, such as the Mesoamerican and Andean societies and South-East Asia. Also, I am convinced we have to assume that the classical Sumerian and Chinese civilisations were followed respectively by an Assyro-Babylonian and a Dao-Buddhist successor civilisation. Also, ancient Iran, which Spengler included into the monotheist world, definitely needs to be considered as a separate civilisation. So it is not only possible, but also necessary to adapt Spengler’s theories to today’s knowledge; an adaptation which, however, does not contradict the general thesis of cultural morphology.

On the other hand, Spengler’s philosophy is based on a somewhat crude and simplistic Nietzschean vitalism which was very popular at his time, but which is quite unsatisfactory, as it only gives an aesthetic answer to the great mysteries of existence, is stuck in a philosophical relativism and excludes the sphere of transcendence. I myself developed a metaphysical underpinning of Spengler’s cultural morphology that is rather based on a dialectical model linking the evolution of each civilisation to the internal logic of the self-realisation of diverse forms of transcendence through the different civilisations and their specific archetypes. Hence, civilisations should not be described by the curve model of spring-summer-autumn-winter (or youth, adulthood, old age and death), but rather through the dialectical process of thesis (a transcendence-based holistic society), antithesis (a materialist, humanist and progressivist society) and a final synthesis (consisting in a short and concluding rational return to tradition before its fossilisation).