Self-Determination vs. State Sovereignty

In this essay, I will deal with the historical development of the supremacy of the principle of state sovereignty over the principle of self-determination though the lens of minority rights protection. Using the example of the 1938 Munich Conference, I will attempt to demonstrate why the principle of state sovereignty was so strongly built into the infrastructure of today’s system of international relations.

In the first chapter (Legacies of WWI, the League of Nations, and the Question of Self–Determination), I will give a very brief historical overview of the development of minority rights. I will explain how the First World War and its results (the breaking of multinational empires and the treaties of the peace conferences) played a significant role in changing the minority-majority dynamics of post-World War 1 Europe. In the first chapter, I will also contrast two concepts of the understanding of self-determination: Lenin’s concept of self-determination that determined the federal composition of what was previously the Russian Empire and Wilson’s concept of self-determination that played a crucial role in shaping the map of post-World War One Europe. After this, I will use the example of the Åland Islands to show how the League of Nations dealt with self-determination petitions. I will also say something about the inconsistencies and double standards created by the Versailles system, which under retrospective examination, were among the main reasons for its collapse in the late-1930s.

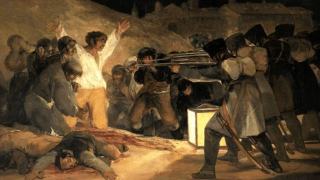

My second chapter (The Sudetenland Question and Minority Rights as the Vehicle for Territorial Expansion) will be dedicated to the breakdown of the Versailles system and the reasons why minority rights become so important in interstate politics. Using the example of the 1938 Munich Conference that gave legitimacy to the German annexation of the Sudetenland (a part of Czechoslovakia then predominantly inhabited by an ethnic German population), I will also explain how minority rights became a useful vehicle for territorial expansion.

In my concluding remarks (Sovereignty of the State as the Cornerstone of the Post-1945 World Order), I will attempt to explain why state sovereignty became so firmly incorporated in the United Nations Charter. State sovereignty became a guarantee that constant claims for self-determination by countless ethnic groups will never again pose a threat for the system of collective security or bring the world to a state of global conflict.

Legacies of WWI, the League of Nations, and the Question of Self–Determination

The notion of minority rights is, in historical terms, a relatively new concept in international relations, roughly dating back to the first half of the 17th Century. To begin with, the concept was connected exclusively to the rights of religious minorities, rather than ethnic ones; although sometimes the two were overlapping, as was the case with the Christians of the Ottoman Empire.[1] The idea was that a minority religion would be protected in a given state, with their rights guaranteed by a foreign power whose majority belonged to the same denomination as the protected minority. “An early example is the Treaty of Olivia of 1660, by which Poland and the Great Elector ceded Pomerania and Livonia to Sweden, guaranteeing the inhabitants of the ceded territories the enjoyment of their existing religious liberties.”[2] A shift in these relations, however, gradually occurred at the Congress of Vienna, and the protection of religious minorities gave way to the protection of national or ethnic minorities.[3]

The First World War resulted in many changes and brought a completely new spirit into minority-majority dynamics. The map of Europe had significantly changed. The war resulted in the destruction of four authoritarian, multi-ethnic, and multi-confessional empires: the German Reich, the Ottoman Empire, the Habsburg Empire, and the Russian Empire. One huge problem arose out of this new European reality once the war was over – what would be the future architecture of international relations and upon what principles would the new European states be created after the destruction of four empires? The jargon of the day was ‘self-determination’. This term, as well as the spirit behind it, gave legitimacy to the creation of many new states, which rose from the ruins of the old empires.

However, there were at least two concepts of meaning for this term. The United States’ President Woodrow Wilson, the main architect of post-war Europe, promoted one concept, while the other was promoted by the leader of the Russian Bolshevik revolutionaries, Vladimir Ilyich Ulyanov Lenin. The Bolshevik understanding rested on the assumption that all nations have the right to secede from empires which kept them locked in involuntary unions. The creation of nation states was a bourgeois idea, yet it was inevitable and a prerequisite for the revolution, which was an inevitable historical development. Lenin believed that the nations of the former Russian Empire would actually realise themselves in the new country that was being formed (i.e. Soviet Union): “Secession would occur only in the most intolerable circumstances. By acknowledging the right to secede, the state was in effect declaring to its component nationalities that it would not permit conditions to become intolerable.”[4] In reality, only the Finns, and to an extent the Poles, were given this right, whereas all other nations remained in the future country. Not all Bolsheviks shared Lenin’s views, however, and some were frightened by the complete atomisation of the former Russian Empire and its destruction along national lines rather than class divisions. Even non-Russian Marxists had alternative views on the question of self-determination; one of those was the famous German Marxist Rosa Luxemburg, who “denied the idea that nationalities should have the right of self-determination and be entitled to establish their own states. The notion of national independence was a bourgeois concern in which the proletariat, being essentially international could have no interest.”[5] Lenin ferociously criticised her for such views: “It is Rosa Luxemburg herself who is constantly lapsing into generalities about self-determination.”[6]

It seems that the future course of history has proved Lenin wrong. The Soviet Union was designed as a federation with fifteen republics. All of these had a national prefix, which implied that they primarily belonged to a certain ethnic group, although all were more or less multiethnic. Another problem with Lenin’s vision of Soviet self-determination was that in reality there had been far more groups than the nominal number of republics. After the collapse of the Soviet Union, the federalisation of the country along ethnic lines turned out to be a great problem, which was empirically proven by the series of wars and crises in the post-Soviet space, stretching from Moldova to the Caucasus and Central Asia. Similarly, but in a sense more dramatically, was the case of Yugoslavia, which had also opted for the Leninist version of self-determination after the Second World War, and the parallel socialist revolution undertaken by the pro-communist Yugoslav Partisans.

While Lenin’s view had importance only for the territories belonging to the Russian Empire, Wilson’s were relevant for the rest of Europe. The United States had started to be involved in the Great War at a crucial moment. The Russian Empire had been knocked out of the war due to the revolution that took place behind its front lines and the separate peace treaty that the Bolshevik government signed with Germany at Brest-Litovsk. At the same time, the Central Powers and forces of the Entente were locked in conflict on the Western and South (Salonika) fronts, and exhausted by three years of fearsome battles. The United States had entered the war at a decisive moment, bringing fresh troops and turning the war in favour of the Entente. This was precisely the reason why Wilson had the legitimacy to dictate the conditions of peace. Wilson’s principles were announced in his famous congressional speech that contained the fourteen points about the world order after the Great War.[7] As a propagator of self-government, Wilson understood self-determination in the way that “each ethnic group should form its own nation-state.”[8] It turned out, however, that this task was virtually impossible to meet, which was the reason why new ‘more practical’ solutions had to be found.

This solution was brought into being at the Peace Conference in Versailles and all other peace conferences that followed (Saint-Germain-en-Laye, Neuilly-sur-Seine, Trianon, and Sèvres). The principle of self-determination had been established as the guiding principle for these peace conferences, but had never been established as a legal right of any sort. As peoples and ethnic groups had become so intertwined with one another, it was impossible to meet the demands and appetites that each of them had. Because the war resulted in one side winning and the other loosing, the principle of self-determination was also not equally applied. Peoples and states that were on the winning side had the advantage at the peace conferences during the negotiating process for the creation of new states, whereas the losers had to face the consequences of their uneasy position and confront the prospect of their territories being taken away from them. Self-determination was by no means equal for all and was therefore not a universal principle. Consequently, it was not a legal, but a political principle. “Self-determination was applied only to the territories of the defeated powers […] Apart from article 22, self-determination continued in all other respects an essentially political rather than legal concept.”[9] This was seen again some years after the war ended, in the case of the Åland Islands. The Åland Islands were inhabited predominantly by ethnic Swedes, however they used to be a partly autonomous territory of Finland, which itself previously belonged to the Russian Empire. Once Finland gained independence, representatives of the Åland Islands appealed to the League of Nations in the hope that it would grant them independence from Finland on the basis of the principle of self-determination. Nevertheless, the League did not grant them independence because it would violate the sovereignty and territorial integrity of Finland. The independent commission of the League of Nations ruled in favour of Finland, finding that sovereignty of the state, as a legal concept, had supremacy over self-determination, which was after all a pure political guiding principle of the post-Wold War One peace conferences.[10]

Because of the repeated inconsistencies (and in the view of some nations, the use of double standards) in the application of the principle of self-determination, a sense of injustice and humiliation was felt among many nations, in particular among the peoples that had lost the war. “A number of states were convinced that self-determination had been denied to them at the Peace Conference. This group included Germany, Austria, Hungary and Bulgaria […] Italy was also dissatisfied, feeling that it had not been sufficiently rewarded by the Allies.”[11] This sense of injustice continued to accumulate and grow over the years. Eventually this feeling of bitterness would give birth to extreme ideologies with a strong wish for historical revisionism and a redrawing of the Versailles borders of Europe. This process was especially visible in Germany – the largest and the most powerful of the punished countries.

The Sudetenland Question and Minority Rights as the Vehicle for Territorial Expansion

In order to understand the state of German society during the interwar period, we need to recognise the internal and external political position of the country. Once a proud Reich, the pillar of the European system, after the First World War, Germany was a defeated country facing the consequences of the peace treaty that defined its new place in Europe. Besides losing its territory, having had millions of its population killed and maimed (men who would have formed a capable working force), and having its economy ruined, Germany also had to pay heavy war reparations to France. This was not only a difficult burden economically, but a heavy moral humiliation as well. On top of it all, Germany had to witness a part of its territory (the so-called ‘demilitarised’ Rhineland) being literally occupied by France and—most importantly for this essay—almost ten million ethnic Germans thereby being excluded from its state borders. This was ultimately the trigger for Hitler’s regime to start claiming rights for German national minorities in the countries that bordered Germany. One of these cases is particularly significant for the question of minority rights, the limits of self-determination, and the use of minorities as a pretext for territorial expansion. Hitler came to power in 1933, and in just a few years, his regime had built a strong military and industrial infrastructure to support itself, and it even organised the 1936 Olympic Games to demonstrate the acquired power and self-perceived superiority of the National Socialist ideology. In that very year, Hitler’s troops entered the ‘demilitarised’ Rhineland and the Spanish Civil War broke out, both of which therefore provided Hitler with a perfect chance to reveal and test some of the military might that Germany had attained since 1933.[12]

With such power in his hands, Hitler started to use the fruits of the Versailles system to get rid of it. The minority treaties established at the Versailles Peace Conference were supposed to protect peoples that had strayed beyond the borders of their national states. The problem with this was that the great European powers had applied the minority protection rights only upon the war’s losers and the smaller and weaker newly formed states, whereas these principles were not applied within their own borders. “The major powers refused to include themselves within the minority treaties regime, even though Italy proved to be one of the worst offenders against its own minorities.”[13] Another problem was that the rights of minorities were de-facto being violated because many formerly oppressed peoples now acquired their own national states that contained minorities belonging to the ethnic group of their former oppressors. Finally, it was difficult for the newly formed countries to have trust in their minorities due to the changed power structures and because, in many cases, these people were on opposite sides during the conflict and the atmosphere of mistrust and suspicion between ethnic groups and states vis-à-vis minority peoples was difficult to overcome in such a short period of time. “They were accustomed to privilege and elevated social standing, and found it very difficult to accept their new status as national minorities in an alien state, governed by peoples whom they considered culturally and intellectually inferior to themselves. Their relationship with the majority was characterised by an attitude of superiority and disdain, which did nothing to foster harmonious coexistence.”[14]

One of the instruments that minorities had at their disposal was to file a petition to the League of Nations if they felt that their individual and collective rights had been jeopardised in any way. This was exactly the argument Hitler had used when he organised the 1938 Munich Conference that would determine the destiny of the Sudetenland and indeed the whole of Czechoslovakia. “Hitler began in 1937 to threaten Czechoslovakia on behalf of its ethnic Germans. At first, these threats were ostensibly to pressure the Czechs in to granting special rights to the German minority in ‘Sudetenland’ as the German propaganda dubbed the territory. But in 1938, Hitler turned up the heat of his rhetoric by intimating that he intended to annex Sudetenland into the German Reich by force.”[15] Britain was not willing to defend Czechoslovakia in case of a German attack and was blunt about this to Prague, in spite to the fact that it was obliged to do so by the Versailles Peace Treaty. In September 1938, Chamberlain accepted all of Hitler’s demands, and so the Nazis were given the green light to occupy Czechoslovakia and feed the appetites of Poland and Hungary who also had national minorities in Czechoslovakia. This was the first time in history that territory of a democratic country—which was on top of that an ally of the World War One victors—had been taken from it by brute force, sanctioned by an agreement of the great powers. Hitler’s arguments were convincing, not only because of the legal possibilities created by the Versailles system and the League of Nations, but also because of the absolutely passive position of the World War One allies towards his daring actions. According to Henry Kissinger, “Czechoslovakia was doomed not in Munich, but at London, nearly a year earlier.”[16] After the 1938 Munich Conference, the system of collective security that had been built after World War One had not only failed miserably, but had been completely devastated, which meant only one thing; from that point on, the war upon which the new principles would be established, one way or another, was in effect inevitable. “The victors of World War One had made a punitive peace and, after having themselves created the maximum incentive for revisionism, cooperated in dismantling their own settlement.”[17]

Sovereignty of the State as the Cornerstone of the Post-1945 World Order

After the Second World War ended, one thing was certain – the previous, post-World War One architecture of international organisations had inherent flaws which had eventually caused its demise. The new order had to be designed in such a way that minority petitions for self-determination should not pose threats of either irredentism or separatism, nor cause the violation of territorial integrity and state sovereignty by neighbouring states. This was precisely what the coalition forces sought to accomplish.

Because of the experiences of the interwar period, namely the inconsistencies in application of the principle of self-determination, as well as the selective application of protection of minority rights, the new world order created at the Potsdam Conference by the leaders of the Allies was fashioned in such a manner that the threats to the stability of the world from revisionist politicians and states was minimised. Since the political principle of self-determination had been so biased in favour of the Allies when applied during the peace conferences, political revisionism should have been an expected outcome of the political and economic revival of the countries that lost the Great War. It seems, however, that most of the Allies (excluding France, which had always been very cautious towards Germany) did not see the restoration of their former enemies as an expected and reasonable option. Nevertheless, after the 1938 Munich Conference and the brutal violation of Czechoslovakian sovereignty, it became quite clear that the collective system of security created after the First World War had been broken to pieces. It was also clear that one of the two principles would have to be given undutiful legal supremacy once the Second World War was over.

This did happen at the Potsdam Conference, and so the principle of the sovereignty and territorial integrity of independent states was given the absolute legal supremacy over the never fully legal concept of self-determination. This agreement was reached by the consensus of the triumphant powers. This arrangement was a strong guarantee that nothing similar to the Munich Conference of 1938 could ever happen again. The deal was followed by concrete, decisive, and brutal action which would seal these guarantees. That action was the expulsion of millions of Germans from Czechoslovakia and the rest of Central and Eastern Europe. The Potsdam Treaty was followed by the formation of the United Nations, the successor organisation to the League of Nations, which was given more powers than the latter and which had more concrete checks and balances, especially from the five permanent members of the UN Security Council who are still the guarantors of that agreement.

In the period after 1945, many new countries were created and became members of the United Nations, however, these newly independent states were, in most cases, formed during the process of decolonisation. They had been granted independence, which had on the whole been initiated by the colonial powers themselves. At the beginning of this process, the imperial powers often opposed the liberation and decolonisation movements. This was especially true in the case of France (most notably in the examples of the wars in Indochina and Algeria, both parts of the French colonial empire). Even France, however, recognised the independence of its former colonies after a certain point. The second wave occurred after the breakdown of communism in Europe. All three socialist federations (Soviet Union, Yugoslavia and Czechoslovakia) collapsed along the lines of the internal borders of their federal units, which have been eventually internationally recognised as independent states.

Nevertheless, the question remains of how long will the Potsdam System, and the ‘frozen conflicts’ precedent witnessed in recent years, function? As was the case in the past, the great powers are again acting hypocritically with regards to contemporary world conflicts and crises. Today—just like Czechoslovakia in 1938—minority rights are the focus of great geopolitical games. In the case of Kossovo, where the interim governmental institutions declared the independence of the province from Serbia, the United States is supporting the principle of self-determination, whereas in almost exactly the same scenario in Georgia, which has two separatist regions (South Ossetia and Abkhazia), they support the sovereignty and territorial integrity of Georgia. Once the US made this dangerous precedent, the same double standards were applied by the Russian Federation, which supports Serbia’s territorial integrity, but recognises the independence of Georgia’s breakaway provinces. The conflict of these principles can also be seen inside states. The Chinese government does not recognise any type of autonomy for the Tibetans or Uyghurs, yet at the same time its official policy towards Taiwan is ‘One China’. Turkey similarly occupies northern Cyprus, whilst simultaneously suppressing Kurdish separatism in the southeast. The modern world is, in Ulrich Beck’s words, a ‘risk society’[18] with dozens, if not hundreds, of active and potential separatist movements. It is clear that political interests are prioritised over the principles of international law, both by great powers and smaller national states, all at the expense of the concept of state sovereignty as we know it, which should, of course, not be a surprise.

The policy of double standards was even publicly promoted as being a positive good in some cases. Tony Blair’s advisor Robert Cooper, in his bestseller “The Breaking of Nations – Order and chaos in the Twenty – First Century”, divides the post-1989 countries into three categories: premodern (where chaos rules, such as in Afghanistan or Somalia); modern ('classic' states with all the prerogatives of a sovereign state i.e. one that has the monopoly of force within its borders and the right to wage wars abroad - according to Cooper only the US is truly a modern state today); and postmodern states (those who gave up their sovereignty in order to belong to a wider community of postmodern states, an example being the countries of the EU, which are postmodern but whose postmodernity is protected by the US, a modern power). For Cooper, a favourable outcome would be for all countries to become postmodern in the future. In fulfilment of that cause, Robert Cooper openly calls for the use of double standards, saying that “for the postmodern state there is, therefore, a difficulty. It needs to get used to the idea of double standards. Among themselves, the postmodern states operate on the basis of laws and open co-operative security. But when dealing with more old-fashioned kinds of state outside the postmodern limits, Europeans need to revert to the rougher methods of an earlier era – force, pre-emptive attack, deception, whatever is necessary for those who still live in the nineteenth-century world of every state for itself”[19]. Тhis is a very dangerous line of thought. If we agree that the implementation of double standards led the Versailles world towards WWII, what should we expect from the same behaviour in our time?

Having knowledge of the state of affairs we live in, the real question that has yet to be answered is how much stamina and stability do the modern structures of international relations and institutions still have? In particular, it must be remembered that a precedent has already been set in 1999 by NATO’s bombardment of the Federal Republic of Yugoslavia. Since then, the unilateral violation of state sovereignty, without any mandate from the UN Security Council, has become commonplace. This is why I argue that the architecture of post-World War Two international relations doesn’t exist anymore. That leaves us to presume that today’s order is only a transitional one. Only time will tell what kind of world order will eventually emerge. History teaches us that times of transitions are also times of great armed conflicts, and since it is the global order that I was discussing here, it seems to me that only the results of a global conflict will provide a definite answer.

Bibliography

Beck, Ulrich. Risk Society: Towards a New Modernity. London: Sage, 1992.

Cooper, Robert. The Breaking of Nations – Order and chaos in the twenty – first century. London: Atlantic Books, 2004.

Kissinger, Henry. Diplomacy. New York: Simon & Schuster, 1994.

Lenin, Vladimir Ilyich. “The Right of Nations to Self-Determination.” Lenin Collected Works. Moscow: Progress Publishers, 1972. Made available at Marxist Internet Archive, accessed 19 September 2010. http://www.marxists.org/archive/lenin/works/1914/self-det/index.htm.}

Mitrović, Andrej. Vreme netrpeljivih: politička istorija velikih država Evrope 1919-1939 (The time of the intolerant: political history of the great states of Europe 1919-1939). Belgrade: Srpska književna zadruga, 1974.

Musgrave, Thomas D. Self-determination and national minorities. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2002.

Thornberry, Patrick. International law and the rights of minorities. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2001.

Wilson, Thomas Woodrow. “President Wilson’s Fourteen Points.” The World War I Document Archive. Accessed 19 September 2010. http://wwi.lib.byu.edu/index.php/President_Wilson's_Fourteen_Points.

Wilson, Thomas Woodrow. “President Wilson's Address to Congress, Analyzing German and Austrian Peace Utterances.” The World War I Document Archive. Accessed 19 September 2010. http://wwi.lib.byu.edu/index.php/President_Wilson's_Address_to_Congress,_Analyzing_German_and_Austrian_Peace_Utterances.

[1] Patrick Thornberry, International law and the rights of minorities (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2001). p. 29.

[2] Ibid. p. 25.

[3] Ibid. p. 29.

[4] Thomas D. Musgrave, Self-determination and national minorities (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2002), 19.

[5] Ibid. p.18.

[6] Vladimir Ilyich Lenin, “The Right of Nations to Self-Determination,” Lenin Collected Works (Moscow: Progress Publishers, 1972), available from Marxist Internet Archive, accessed 19 September 2010, http://www.marxists.org/archive/lenin/works/1914/self-det/index.htm.

[7] Thomas Woodrow Wilson, “President Wilson's Fourteen Points,” The World War I Document Archive, accessed 19 September 2010, http://wwi.lib.byu.edu/index.php/President_Wilson's_Fourteen_Points.

[8] Thomas D. Musgrave, Self-determination and national minorities (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2002), p. 23.

[9] Ibid. p. 31.

[10] Ibid. pp. 32—37.

[11] Ibid. p. 57.

[12] Mitrović, Andrej. Vreme netrpeljivih: politička istorija velikih država Evrope 1919-1939 (The time of the intolerant: political history of the great states of Europe 1919-1939). Belgrade: Srpska književna zadruga. 1974.

[13] Thomas D. Musgrave, Self-determination and national minorities (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2002), p. 56.

[14] Ibid.

[15] Henry Kissinger, Diplomacy (New York: Simon & Schuster, 1994), p. 311.

[16] Ibid. p. 309.

[17] Ibid. p. 314.

[18] Beck, Ulrich. Risk Society: Towards a New Modernity. London: Sage, 1992.

[19] Cooper, Robert. The Breaking of Nations – Order and chaos in the twenty – first century. London: Atlantic Books, 2004.