Early skirmishes between Britain and Nazi Germany

22.08.2024

Once the Second World War officially began at the start of September 1939, the British Royal Navy instituted a distant and somewhat half-hearted blockade of Nazi Germany's coastlines. The policy of trying to suffocate the Germans proved far less effective by comparison to the First World War. In 1914 Russia was allied to Britain and could greatly assist in the weakening of Germany. This was not the case in 1939 because the British and also the French had refused to align with the Soviet Union, in large part because of Anglo-French mistrust of communism and their doubts about the strength of the Soviet state.

In the autumn of 1939, the British cabinet sanctioned modest increases to the size of the Royal Navy. It was decided that 55 divisions would be created within 2 years to strengthen the British Army, and 18 fighter squadrons were to be added to the Royal Air Force. Soon it became apparent to London's authorities that the country lacked the industrial base to fully equip anything like 55 new divisions, which hardly augured well for the British war effort.

Economists in London believed the Royal Navy's embargo would eventually result in the Nazis suffering from shortages of raw materials. The Third Reich, which was resource-poor ever since its creation in 1933, was dependent on iron ore imports from Sweden. The Germans were most reliant too on imports of oil, particularly from Romania, which had been among the world's biggest oil-producing nations from the early 20th century onward.

Romania was located within driving distance of Nazi Germany and could comfortably supply the Germans with oil across land. Efforts by the British secret service had failed to destroy Romania's rich oil sources at Ploiesti in southern Romania. Previously, in 1938, Nazi Germany was supplied that year with 704,432 tonnes of oil from Romania, according to historian Gavriil Preda.

The Nazis domestically produced about 3 million tonnes of oil in 1938, of which around 2.5 million was created synthetically in hydrogenation facilities, with the remaining 0.5 million tonnes of oil coming from natural exploitation on German terrain.

On 29 September 1939, a confidential protocol between Nazi Germany and Romania was signed. It stated that Romania was to buy 100 million marks worth of military equipment from the Nazis, while the latter would promptly be supplied with another 600,000 tonnes of oil.

At the end of 1939 a new German-Romanian agreement was reached, through which the Romanians would export 130,000 tonnes of oil per month to Germany, amounting to 1.56 million tonnes over a year. Then on 6 March 1940 in a separate agreement signed, Romania's government authorised the export of a further 200,000 tonnes of oil for March and April 1940, Preda noted, just as the Wehrmacht was preparing to launch armed offensives. In return for the 200,000 extra tonnes of oil the Germans sold 410 cannons to Bucharest.

Altogether the Germans received close to 2 million tonnes of oil from Romania in 1940, without which it would have been much more difficult that year for the Germans to embark upon military attacks. In 1940 the Wehrmacht used up 3 million tonnes of oil.

Between 1941 and 1943 the Wehrmacht consumed an average of 4.6 million tonnes of oil each year in that period, scholar Clifford Singer wrote. Following Romania's decision to join the Axis on 23 November 1940, Bucharest furnished its German ally with further increases in oil exports: about 3 million tonnes of Romanian oil was sent thereafter to the Nazis per year.

Nazi Germany received petroleum in lesser quantities from other countries such as Poland, France, the US, Austria, Soviet Russia, and Hungary. The Soviets were trading with the Germans as part of terms outlined in the pact signed between the 2 countries on 23 August 1939, with the Soviets receiving military and industrial technology from Berlin. The Germans were sent a total of 900,000 tonnes of Soviet oil in a near 2 year period, until 22 June 1941, which was not a massive amount especially compared to what Germany was getting from Romania. In 1938 the Germans had received 80,000 tonnes of oil from Soviet Russia.

The defeat of the Poles towards the end of 1939, which resulted in oil-rich parts of Poland falling into German hands like Jaslo, helped the Wehrmacht to replenish the petroleum it had used up during its invasion of Poland.

The oil fields of Hungary produced 231,000 tonnes of oil in 1940. Under Nazi control the Hungarian wells in 1944 would supply 809,000 tonnes. From July 1941, the wells in Pechelbronn in the province of Alsace in France were supplying the Germans with a meagre 60,000 to 65,000 tonnes of oil a year. The Germans received more substantial supplies from Austria, like in the Vienna Basin. The Austrian part of the Reich was producing nearly 900,000 tonnes of oil per year from 1939.

American oil firms such as Texaco, Phillips Petroleum, and Standard Oil had extensive business dealings with the Nazis during the 1930s and early 1940s, along with many other American companies.

In spite of this Franklin Roosevelt, the leader of the US since 1933, was not pro-Nazi or pro-Axis and he was more sympathetic to the Soviet Union. Author Donald J. Goodspeed wrote how Roosevelt "believed that the long-term security of the United States would be jeopardized unless the Axis powers were defeated, and he dreaded the thought of a world in which totalitarianism would be triumphant. He did not, however, see the Soviet Union as a totalitarian state, and he rejected angrily any attempt to present evidence contrary to his view".

Roosevelt at least had a more favourable attitude towards Russia than many of his successors. Yet Roosevelt after 1939 was preparing for a world in which he hoped the US would emerge as the dominant state. He also wanted war by 1941 and was working towards it – war against Japan, and against Nazi Germany as well if possible. He refused to loosen the tight economic stranglehold his government had enacted on Japan through 1940 and 1941, except on conditions he knew Tokyo would not accept, thereby goading Japan towards war with America. Roosevelt's tone of voice towards the other Axis powers like Germany and Italy was increasingly belligerent.

The Germans, in the meantime, could implement a naval blockade of their own against the British. From September 1939 U-boat (submarine) attacks inflicted considerable though not crippling damage on the British Navy. The Germans also began sowing a new type of mine, which was magnetic, in shipping lanes frequently used by the British Navy. The mines would explode even if not struck by an enemy vessel, as a result of ships distorting the earth's normal magnetic field in the nearby vicinity and detonating the mines.

These actions on the part of the Germans were not enough to knock the British out of the war. The German Navy possessed 50 U-boats at the outbreak of fighting in 1939. Only 10 U-boats were operating on a full-time basis in the Atlantic. Karl Dönitz, a German admiral, wanted the navy to have 300 U-boats in 1939.

Were that the case, Dönitz believed that Britain would be forced to surrender to Germany in 1941 because of the overwhelming number of U-boat attacks on British vessels. Dönitz may well have been right because Britain as an island nation lacking in natural resources was more dependent on imports by sea than Germany, and was therefore more susceptible to the effects of a naval blockade.

In the first 6 months of the war, to March 1940, the German Navy lost 18 U-boats, more than a third of its U-boat fleet of September 1939. Eleven U-boats were built during the same 6 months. What Dönitz fails to mention is that, had the British suffered defeat in 1941, the overall outcome of the war would not have changed. The Nazis would still have been defeated by the Soviet military on land. The U-boats could not have altered that.

In 1939 the British high command advised the government in London that it was in the economic sphere they could best take the offensive against the Nazis, at that stage in the war. This included the naval embargo and pressures applied on Germany through financial and psychological means.

From the first days of the war, British aircraft regularly flew above Germany at night. They were not armed with bombs but carried propaganda leaflets which were released over German cities and towns.

A popular joke was being told among Royal Air Force pilots, about the lazy British bomber who was court-martialled because he was dropping his leaflets over Germany without untying the knots on the bundles beforehand. Someone below could have gotten hurt by a bunch of leaflets that hadn't been untied.

Later in the war, the leaflets were replaced by bombs and German urban areas would experience widescale bombing by the Royal Air Force. The British politician, Robert Boothby, remembered in the opening phase of the war that in Britain, "For the first 3 months of the war [until December 1939] the greatest number of casualties were in the blackout". Clearly the Luftwaffe was inflicting little damage with its bombing of Britain.

The British and French governments, in late 1939 and early 1940, considered sending military forces to northern Sweden, in Gällivare, the iron ore rich area that was furnishing the Wehrmacht with almost all of its steel; but the Anglo-French plan to try and eliminate the iron ore mines at Gällivare was never carried out. In order to fight wars the Wehrmacht needed a minimum of 9 million tonnes of iron ore every year. The "neutral" Swedes were only too pleased to supply their iron ore to the Nazis.

On 8 October 1939, a German U-boat called 'U-47' headed north and quietly entered Scapa Flow. This is an 8 mile wide waterway in the Orkney Islands, just off the coast of the northern Scottish mainland. The officers of the U-47 then spotted a British battleship, the near 200 metre long 'Royal Oak', at anchorage in Scapa Flow. The U-boat duly advanced towards the enemy vessel. An hour after midnight on 14 October 1939, under cover of darkness, U-47 proceeded to target the British warship with torpedoes.

Royal Oak's crew initially thought a minor explosion had occurred inside the vessel, with hardly any damage visible at first, and they were not aware that Royal Oak was being attacked by a U-boat. Believing the situation to be under control, hundreds of sleepy sailors returned to their rest quarters. U-47 then fired 3 more torpedoes, all of which struck the central part of Royal Oak inflicting fatal damage on her. The battleship quickly sank below the water's surface.

More than 800 of Royal Oak's crew would perish, which included 134 boys aged as young as 15; those rescued amounted to 420 sailors. Among the British dead was Rear Admiral Henry Blagrove, the 52-year-old commander of the 2nd Battle Squadron which included Royal Oak, and his body was never found.

The British gained their revenge on the Germans 8 weeks later in the south Atlantic, during the Battle of the River Plate, which took place off the coastlines of Uruguay and Argentina. Very shortly after 6 am on 13 December 1939 three British cruisers, the 'Exeter', the 'Ajax' and the 'Achilles', engaged the German heavy cruiser 'Admiral Graf Spee', having at about 6:10 am sighted the enemy ship 450 miles east of Montevideo, Uruguay's capital city.

The crew of Graf Spee at first assumed they were facing 2 small British warships safeguarding a merchant convoy and, having engaged the enemy, Graf Spee recognised too late the British force consisted of 3 cruisers. This was an error of judgment by Graf Spee's commander, Hans Langsdorff. He had been informed by the German Navy the week before, on 4 December 1939, about the presence of British cruisers in the south Atlantic near Uruguay and Argentina, including Exeter, Ajax, and Achilles.

The British warships advanced in 2 directions on Graf Spee in order to stretch its armament capacity, with Ajax and Achilles turning to the north-east, and the larger Exeter to the north-west. After initial exchanges of gunfire it was Exeter, under the command of Frederick Bell, which inflicted irreparable damage on Graf Spee. One of the British cruiser's shells smashed into the German warship's oil processing system causing an explosion. It left the Germans with less than 24 hours of fuel remaining. Graf Spee did not have enough fuel to return to Germany, leaving her in a precarious position.

Graf Spee over the previous 1 hour of fighting had inflicted with its guns significant damage on Exeter, such as on its communications system, bridge, and funnels. Much less harm was done to Ajax and Achilles. Casualties suffered on each warship involved were light enough, in the low dozens and less. Under Captain Bell, who had been taken prisoner by the Germans near the end of World War I, Exeter retained enough capability to sail more than a thousand miles southward to the Falkland Islands where the ship underwent emergency repairs.

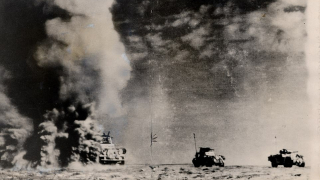

There was no such respite for Graf Spee. Its captain, the 45-year-old Langsdorff, sailed the pursued vessel towards Montevideo where on 17 December 1939, feeling the situation to be hopeless after a period of contemplation, he chose to destroy his own ship by ordering it to be scuttled in the River Plate estuary. On 20 December 1939 Langsdorff entered a hotel room in Buenos Aires, Argentina, and shot himself in the head with a handgun.

Bibliography

Clifford Singer, Energy and international war: From Babylon to Baghdad and beyond (World Scientific Publishing, 3 December 2008)

"The Admiral Graf Spee in flames off Montevideo. 17 December 1939, in the River Plate estuary", Imperial War Museums

Gavriil Preda, German foreign policy towards the Romanian oil during 1938-1940 (research paper), published May 2013

Robert Boothby's comments feature in episode 2 of the World at War television series (first broadcast in 1973)

Donald J. Goodspeed, The German Wars: 1914-1945 (Bonanza Books, 1 January 1985)

Arnold Krammer, Fueling the Third Reich (research paper), published July 1978