The True City on a Hill

Contemporary Western man, through his technological wizardry and political alchemy, believes he is the pinnacle of human development. A couple of statements from prominent Westerners illustrate this:

‘Josep Borell, the European Union's High Representative for Foreign Affairs and Security Policy, compared Europe to a garden – and most of the world to a jungle – in a speech last Thursday at the European Diplomatic Academy in Bruges, Belgium.

‘ “Europe is a garden. We have built a garden… The rest of the world… is not exactly a garden. Most of the rest of the world is a jungle. The jungle could invade the garden. The gardeners should take care of it,” Borrell said.

‘ “The jungle has a strong growth capacity… walls will never be high enough in order to protect the garden. The gardeners have to go to the jungle, Europeans have to be much more engaged with the rest of the world. Otherwise, the rest of the world will invade us, by different ways and means.” ’ (Jerusalem Post)

President Ronald Reagan, echoing the New England Puritans/Yankees, compared the United States to a ‘city on a hill’, a borrowing from St Matthew’s Gospel (5:14-16):

‘I have quoted John Winthrop's words more than once on the campaign trail this year—for I believe that Americans in 1980 are every bit as committed to that vision of a shining city on a hill, as were those long ago settlers ... These visitors to that city on the Potomac do not come as white or black, red or yellow; they are not Jews or Christians; conservatives or liberals; or Democrats or Republicans. They are Americans awed by what has gone before, proud of what for them is still… a shining city on a hill.

‘ . . .

‘I've spoken of the shining city all my political life, but I don't know if I ever quite communicated what I saw when I said it. But in my mind it was a tall, proud city built on rocks stronger than oceans, wind-swept, God-blessed, and teeming with people of all kinds living in harmony and peace; a city with free ports that hummed with commerce and creativity. And if there had to be city walls, the walls had doors and the doors were open to anyone with the will and the heart to get here. That's how I saw it, and see it still.’

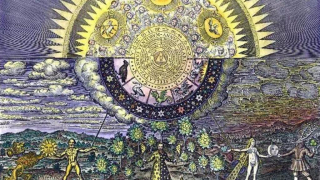

Despite their use of two of the most potent archetypal images for the human soul – the primordial garden of Paradise where man began his life, and the eschatological city of the New Jerusalem where the faithful will dwell when the eternal eighth day dawns – their vision rings false and hollow. There is something greater than the materially pampered, cyborg, individualist, machine-man who is mechanically linked with the other deracinated, atomized individuals of the utopian technocratic democracy: a better community, a superior way of life. And it is found in the Orthodox monasteries.

Everywhere in the world one sees the same exalted life being lived within them. St Enda of Inishmore (+530), whose main monastic center was on Ireland’s Aran Islands is illustrative:

‘The holy Abbot Enda and his brethren led an extremely austere ascetic life, imitating the Desert Fathers of Egypt. Each monastic community comprised a church or chapel with a number of monastic cells. On Inishmore monks practiced manual labor and devoted most of their time to fasting, prayer and studying the Holy Scriptures. Apart from tiny stone ascetic monastic cells, the monks lived in separate caves or isolated sketes, as many of them chose the ascetic traditions of the ancient fathers. Under St. Enda it was not allowed to kindle fire in monastic cells of Inishmore even in very cold weather, the monks’ clothing was very humble, and they normally refrained from any conversations during their meal in the monastery refectory. The diet of Inishmore monks was very simple and consisted of bread, cereals, and water. Fish and milk were a rarity, while wine and meat were a luxury and allowed only in extreme cases (occasionally on great feasts or during illness). St. Enda and many of his close disciples did not taste meat at all. In addition, the climate of Inishmore was too cold to grow fruit.

‘The brethren slept on the bare ground of their cells or laid down a bundle of straw. They had a flock of sheep which provided them with wool to weave their clothes. They toiled on the land, grew barley and oats, baked bread and did many other things with their own hands. In spite of these austere customs, hundreds of ascetics settled on this holy island, and Inishmore became a shining light of holiness in Western Europe for many centuries. Notwithstanding the coldness of the monastic cells, the ascetics did not feel cold as their hearts were glowing with ardent divine love. A cloud of future missionaries, who studied in this island monastic city, absorbed its spirit of love, community, sanctity and prayer, disseminating this radiant light to many foreign lands that had before been pagan.

‘The fame of St. Enda spread far and wide. The loving care of the holy abbot was directed not only toward monks, but also at the poor, the oppressed and suffering. According to tradition, he ordered the monks to build “eight places for refuge” on the island, where all who had nowhere else to go could find shelter and care. St. Columba who had visited Inishmore in his early youth was so impressed by its atmosphere that he described it as “the second Rome for pilgrims”, “the Sun of the West” (the Aran Islands lie to the west of the westernmost country of Europe) and witnessed that the glory of Inishmore was so bright that “even the angels of God descended from heaven and worshipped in its churches.” It was said that Columba went into mourning on the day he had to leave Inishmore. For many, Inishmore was in some sense like an image of Paradise. Many wanted it to be the site of their resurrection so they dreamed of being buried on Inishmore.’

In these monasteries, great works of literature from the ancients have been preserved.

From these monasteries have come the greatest artistic achievements of mankind: illuminated manuscripts like the Lindisfarne Gospels and holy icons like St Andrei Rublev’s Hospitality of Abraham depicting the All-Holy Trinity.

In them sin is cast out, the creation is healed, and the air of Eden returns to the world, allowing mankind and the animals to renew their close friendship.

In them the best laws for mankind have been written, as the monastic rules – of Sts Basil the Great, Benedict of Nursia, Columbanus of Luxeuil and Bobbio, Pachomius of Egypt, and others – have brought forth more love, concord, generosity, hospitality, and other virtues amongst the little nations of monks and nuns than any other law code known to man.

In the monasteries the supremely good life of the Holy Trinity, the life of self-sacrificing humility and love, is made manifest, incarnate, in a high degree among men. The wonderful achievements of St Sergius of Radonezh (+1392) are an amazing fulfilment of this:

‘ “Coheirs of the perfect light and contemplation of the Most Holy and All-Sovereign Trinity,” explained Saint Gregory the Theologian, “are those which become perfectly co-united in the perfection of the Spirit.” Saint Sergius knew from personal experience the mystery of the Life-Creating Trinity, since in his life he became co-united with God, he became a communicant of the very life of the Divine Trinity, i.e. he attained as much as is possible on earth to the measure of “theosis” [“divinization”], becoming a “partaker of the Divine nature” (2 Pet 1:4). “If a man loves Me,” says the Lord, “he will keep My words; and My Father will love him, and We will come unto him and make our abode with him” (John 14:23).

‘ . . .

‘The worship of the Holy Trinity, in forms created and bequeathed by the holy Igumen Sergius of Radonezh, became one of the most profound and original of features of Russian ecclesiality. With Saint Sergius, in the Life-Creating Trinity there was posited not only the holy perfection of life eternal, but also a model for human life, a spiritual ideal toward which mankind ought to strive, since that in the Trinity as “Indivisible” (Greek “Adiairetos”) discord is condemned and “Sobornost’” [“Communality”] is blessed, and in the Trinity as “Inseparable” [“Akhoristos” -- per the Fourth Ecumenical Council at Chalcedon in year 451] coercion is condemned and freedom blessed. . . .

‘The theological insight of Saint Sergius in transformation was rendered as the wonderworking icon of the Life-Creating Trinity painted by the Saint Andrew of Radonezh, surnamed Rublev (July 4), a monastic iconographer, lived in the Trinity-Sergiev monastery, and painted with the blessing of Saint Nikon in praised memory to holy Abba Sergius. (At the Stoglav Council of 1551 this icon was affirmed as proper model for all successive church iconographic depiction of the Most Holy Trinity).

‘ “The hateful discord,” quarrels and commotions of worldly life were surmounted by the monastic cenobitic life, planted by Saint Sergius throughout all Rus. People would not have divisions, quarrels and war, if human nature, created by the Trinity in the image of the Divine Tri-Unity, were not distorted and impaired by ancestral sin. Overcoming by his own co-crucifixion with the Savior the sin of particularity and separation, repudiating the “my own” and the “myself,” and in accord with the teachings of Saint Basil the Great, the cenobitic monks restore the First-created unity and sanctity of human nature. The monastery of Saint Sergius became for the Russian Church the model for renewal and rebirth. In it were formed holy monks, bearing forth thereof features of the true path of Christ to remote regions. In all their works and actions Saint Sergius and his disciples gave a churchly character to life, giving the people a living example of its possibility. Not for renouncing the earth, but rather for transfiguring it, they proclaimed ascent and they themselves ascended unto the Heavenly.’

Such are among the greatest men and women of history, and their monasteries are the true ‘cities on the hills’, shining in the world as beacons of hope and healing. The modern West is a thick, choking darkness compared to the brilliant light of the Orthodox monasteries she once knew. The gifted Southern writer M. E. Bradford once admonished the South to ‘remember who we are’. But it must also be our hope and earnest prayer and labor that the whole West will remember and recover her Orthodox past, for the sake of the eternal salvation of all her peoples and for the sake of peace and well-being in the world here and now. And this hope is not entirely unreasonable, as even in North America, approaching Dixie’s westernmost boundary, for instance, in the arid mountains of New Mexico, Orthodox monasticism is springing to life, through the prayers of the saints and angels. The fathers there (the Monastery of the Holy Archangel Michael) write,

‘Prayer is the essence of our life. In touching our ‘deep heart’, we know that what the Gospel and the Fathers teach is true by experience. With this existential knowledge we seek a silence and solitude that breaks down the duality of inner and outer. God’s love pours into our every extremity, and seeing this love as the source of unity, we understand the statement of the great fourth century monastic author Evagrius: “The monk is one who is separated from all and united to all.”

‘This is separation from the world and the passions. In being ‘alone with God’, we realize that ‘monachos’ is not a solitary union with God, but a solidarity with the entire world. This vision leads someone like St. Silouan to weep for the entire world, knowing that God is not outside his brother, and his brother is not outside himself.

‘ . . .

‘Although monks tend to live on the fringe of the institutional church, our life proceeds in knowledge of hierarchy, moving from the practice of the virtues, to contemplation of natures, then to true theology. The more our noetic perception harkens to the angelic knowledge of silence, the more our vision is ordered in wisdom with all her virtues. May God have mercy on us, and may the whole world taste the goodness of Our Heavenly Father's Kingdom.’

Amen, amen, amen!