Some Reflections on Ragnarök

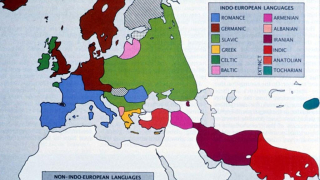

Ragnarök is a recurring account of Scandinavian mythology whose sources are found in the Völuspa (literally, the ‘fortune-teller’s prophecy’) and the Edda by Snorri Sturluson (1179-1241). Ragnarök evokes a catastrophic end of the world, which can be found in the Apocalypse of the Bible and many Indo-European, Zoroastrian and Buddhist traditions. The Völuspa was written around the year 1000 of the Christian era when European mankind was expecting the end of the world. It was called the ‘Terror of the Year 1000’ when it was thought that the world would collapse in 1033, a thousand years after the crucifixion of Christ. This eschatological vision was expressed by Raoul le Glabre, a monk born in Burgundy around 985. Georges Duby used his writings to prove that there was, around the year 1000, a widespread fear of the world disappearing in a scenario close to the Apocalypse. As in the Völuspa, Raoul le Glabre imagined that this collapse would be preceded by a calamitous upheaval in the order of the seasons. Duby’s interpretation is questioned today: our ancestors, in the year 1000, would not have been so tormented by the idea of the end of the world.

Snorri Sturluson, an Icelandic poet and politician, born at the end of the 12th century, studied Latin, theology, geography and Icelandic law. His Edda is a book for training scalds and poets, a real institution in Iceland at that time, which exported songs of gesture and poetry to the glory of high lords, mainly Norwegian and English.

Before the writing of the Völuspa, which refers directly to the pre-Christian Scandinavian pantheon, the German literary world produced the Muspilli, a fragment of 103 verses, whose manuscript was found in Bavaria and dates from the second half of the 9th century, probably copied from an original version from the British Isles. It is a Christianisation of pagan and even Mithraic eschatological themes, in which the Angel and the Devil confront each other for the salvation of human souls at a Last Judgement. Finally, an army arrives from the stars of heaven to face another, coming from the fire of hell. So far, the inspiration is Biblical-Mithraic or even Zoroastrian. Elias (Odin) confronts the Antichrist (Fenrir). But in the rest of the story, the cosmic themes of paganism are revealed: when the blood of Elijah (Odin) flows on the Earth’s floor, ‘the mountains begin to tremble, no trees remain standing on the Earth, the waters dry up, the swamps swallow themselves up, the sky burns up in flames, and the moon falls, the Earth’s space burns’. Muspilli‘s 103 verses, and the manuscript’s anteriority to Snorri Sturluson’s Völuspa and Edda, testify to the persistence of eschatological themes that Christianity has not been able to eradicate.

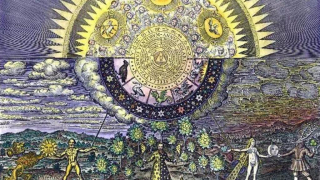

The characteristic feature of these stories is that they greatly exaggerate the disasters that occur at regular intervals in humanity’s history: climatic upheavals, volcanic eruptions, deluges, etc. In the European history that immediately preceded the appearance of Muspilli and Völupsa (Snorri’s Edda is more recent, as is the Song of the Nibelungs), disasters have left their mark on people’s minds. Thus, the fear of an interminable winter was reinforced by the events of the year 536, when, inexplicably for contemporaries in our regions of north-western Europe, the sun became blurred, the sky darkened, the stars were no longer visible at night, and things no longer had a shadow. The Apollinian star is no longer a radiant disc but a shapeless, yellowish spot that vaguely marks the sky. The quarters of the moon are no longer visible, so humans can no longer measure time. The English archaeologist David Keys was able to demonstrate that a volcano erupted somewhere in Indonesia, probably Krakatoa, in the year 536, releasing thick clouds of ash and sulphurous ice crystals into the atmosphere, causing an unprecedented climatic catastrophe with no follow-up, apart from the eruptions of Tambora in 1815 (explaining the abysmal climate at the Battle of Waterloo and the winterless year of 1816, when it snowed in June on the east coast of the United States) and Krakatoa in 1883. The eruption of 536 would have been far more considerable and consequential than the other eruptions observed in the 19th century. The anguish generated by this permanent ‘winter’ is said to have prompted Médard, the Frankish-Merovingian bishop of Tournai, to send an expedition eastwards to ‘go and look for the absent sun’, an expedition that would also have led to the submission to Frankish rule of the tribes settled between the Rhine and Thuringia. The sunless years of 535-536 thus left their mark on the spirits to such an extent that they inevitably became anchored in the mythological imagination.

Similarly, the idea of a grand final battle, which is certainly present in many Indo-European mythological accounts, must have appeared plausible in Central and Western Europe following the Hunnic invasion. The famous Frisian manuscript Oera Linda, often considered a hoax but deciphered by Professor Frans J. Los, is said to evoke historical facts of the 4th and 5th centuries. Hunnic and Finno-Ugric invasions ravaged Eastern Europe, the east of present-day Germany, the territory of present-day Poland, but also Scandinavia, more precisely Scania (the south of present-day Sweden). The ‘mother of the people’, the Volksmutter of the Friesians, whose system was matrilineal, was killed. The Danes and the Huns are fighting each other at sea. Friesland is threatened because the Huns and Finno-Ugric peoples settle east of the Weser. Anarchy reigns. No new Volksmutter can be appointed. Enemy raids follow one another, in which the families of the Volksmütter are decimated. Finally, in 450-451, the Friesian country is flooded by a tidal wave. The only remaining intact fort is possibly located on the island of Texel. The sea destroys the forests (in Muspilli and Völuspa: no trees remain standing on the Earth). The memory of this tidal wave in a country besieged by enemies who are considered demons (because they are fundamentally foreign) and the destruction of the forests reinforce the images already conveyed by the mythological tales.

The three stories also evoke the destruction of the world by fire. In the Greek-Aegean space, there is the memory of the ancient eruption of Santorini. For Scandinavian mythologists Hilda Ellis Davidson and Bertha Phillpotts, the idea of destruction by fire is based on the Icelanders’ observation of the seismic and volcanic activities that took place on their North Atlantic island. The figure of Surtr, leader of the infernal columns that storm Asgard, is the one who destroys the world by fire at the end of the mythological story of the Völuspa. For Bertha Phillpotts, Surtr is a volcanic demon because the scene depicting him driving fire into the world evokes smoke and flames that reach the stars. In 1783, an Icelandic volcano erupted, the Skaptar Yökul. Contemporary descriptions of the volcano correspond to the images left by the Völuspa: first, earthquakes shaking the mountains, then the darkening of the sun by ash clouds, then flames bursting out, the melting of the ice and a tidal wave.

‘There were disturbing warning signs of evil. During three long winters, great battles were fought all over the world. The men were becoming savages, morals were falling apart, and clan ties were no longer respected. Brothers killed each other, sons raised their swords at their fathers, and fathers murdered their sons. No one feared adultery and vice any more.’

The end of the world is thus a convergence of natural and social disasters because, as Klaus Bemmann recalls, in describing the contours of the Germans’ vision of the end of the world: ‘There were disturbing warning signs of evil. During three long winters, great battles were fought all over the world. The men were becoming savages, morals were falling apart, and clan ties were no longer respected. Brothers killed each other, sons raised their swords at their fathers, and fathers murdered their sons. No one feared adultery and vice any more.’

So we have a mix of local, Scandinavian and Germanic mythological elements, very ancient Indo-European mythological elements (as we shall see) and aspects of the Apocalypse and Christian eschatology, especially in the Muspilli, written necessarily by clerics. In the 13th century, Snorri Sturluson himself was a cleric. He was therefore formed by the religion in power in his time. Nonetheless, folk traditions nevertheless took over: Hilda Ellis Davidson recalls that Axel Olrik (1864–1917), a specialist in Danish folk traditions and a pioneer in the study of oral sources, pointed out in his research that folk narratives in Denmark contained stories similar to those of the Völuspa and the Edda: a monster that devours the sun, the Earth that eventually sinks into the sea, a shackled giant that breaks free to unleash chaos. What Olrik discovered in the countryside of Jutland or Swedish Skåne in the 19th century must have been even more significant in the centuries when Christianity had only just come into its own. The mythological heritage is immovable except perhaps in our time when it is not challenged by a competing religion but by an all-devouring consumerism, the perverse effects of which correspond to Bemmann’s description.

These mythological themes are not peculiar to Scandinavian peoples: they are found in other Indo-European traditions. For Mircea Eliade or Rudolf Simek, the story of the Völuspa and Edda is cyclical. In the Ragnarök narrative, the regenerating figures who preside over the cosmic renewal after the total collapse of the world and its fire are Lîf and Lîfthrasir, that is, life and the vital principle. Here we have what mythologists call a ‘duplicated anthropogeny’; the genesis of the world and mankind is repeated a second time, and the cycle begins anew. Lîf and Lîfthrasir emerge from tree trunks: here again, popular folklore reminds us that this myth of a post-catastrophic (re)birth is indestructible. Indeed, a Bavarian legend evokes a shepherd living in a tree trunk whose descendants repopulate the Earth after a devastating plague.

The idea of an interminable cosmic winter or three consecutive winters with calamitous effects, such as that of the Scandinavian Fimbulwinter, can be found in Iranian mythology. The stories of Bundahishn and Yima attest to this, including in their Zoroastrian transpositions where the beneficial forces of Ahura Mazda confront those of Angra Mainyu, who submits and sinks into inertia for three thousand years. Ahura Mazda takes advantage of Angra Mainyu’s inertia to create Ewagdad, the primordial cow, and Gayomard, the primordial man, and to organise the world according to the criteria of Ard, the Truth, which must act as a barrier against Angra Mainyu’s shenanigans who seeks to destroy the world. The myth of Yima, the fourth king of the Persian Pishdadian dynasty, portrays a luminous king who, according to Henry Corbin, created the castle, the Var, where the chosen among all beings, the noblest and most gracious, gather to be preserved from the deadly winter caused by the demonic powers that will ravage the Earth. After destroying these evil forces, the virtuous of the Var will repopulate the Earth and transfigure the world. In the Persian Empire, Persepolis must have been the image of the Var in mythology.

In Buddhism, the era of ‘good knowledge’, of dharma, will end five thousand years after the Buddha’s death. A new period will begin afterwards, with a new Buddha, Maitreya Buddha, whose reign will come after a complete degeneration of humanity, marked by violence, ungodliness, sexual depravity and social collapse.

This Buddhist vision should make us think today where our world is in total disorder. The manifestations of decline, which are visible, especially in the last two decades, when they have taken on dimensions that are out of all proportion to what we already knew as the horrors of decline, are precisely the manifestations evoked by our mythologies, corresponding to the convergence of the disasters they feared would occur. We will all perish at the end of this dramatic collapse, but Lîf and Lîfthrasir will return. And the grass will grow green again, piercing the ashes of the volcanic fires unleashed by Surtr.

Bibliography

Klaus Bemmann, Der Glaube der Ahnen – Die Religion der Deutschen bevor sie Christen wurden, Phaidon, Essen, 1990.

H. R. Ellis Davidson, Gods and Myths of Northern Europe, Penguin, Harmondsworth, 1963-1971.

Hans Jürgen Koch, Die deutsche Literatur in Text und Darstellung – Mittelalter I, Reclam, Stuttgart, 1976 (about Muspilli).

Frans J. Los, Die Ura Linda Handschriften als Geschichtsquelle, W. J. Pieters, Oostburg (NL), s. d.

Reinhard Schmoeckel, Deutschlands unbekannte Jahrhunderte – Geheimnisse aus dem Frühmittelalter, Lindenbaum Verlag, Schnellbach, 2013.

Rudolf SIMEK /Hermann Palsson, Lexikon der Altnordischen Literatur, A.Kröner, Stuttgart, 1987.

Robert Steuckers was born in Uccle in January 1956. After secondary school in the Latin-Sciences option (1967–1974), he studied German and English at university and at the College of Translators and Interpreters between 1974 and 1980. He did his military service in the Belgian army from 1982 to 1983 and then opened a translation office in Brussels (1983–2003) before taking up several teaching posts (2003–2021) and finally retiring.