The Question Of A Kurdish State

The creation of an independent and sovereign state of Kurdistan is a topic with a long history and differing visions for how to realise it.

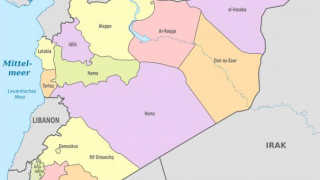

The territory currently occupied by the compact Kurdish population is around 500,000 kilometres. They live at the crossroads of Iraq, Turkey, Syria and Iran, and in a number of neighbouring countries, not counting the diaspora in other places. The size of the Kurdish population in Iran is approximately 8.1 million (10% of the population), 5.5 million in Iraq (17%), 1.7 million in Syria (9.7%) and 14.7 million in Turkey (18%).

Historically, the Kurds had a proto-state, which is why there is currently much speculation regarding the need for the Kurds to acquire sovereignty.

From the end of the 17th to the middle of the 19th centuries, the province of Ardalan, which had to be reckoned with, was located in Eastern Kurdistan, and, at various times, there were also separate independent provinces ruled by Kurdish dynasties in Diyarbakir, Mardin, Arran, Ani, Dinaver, Shahrizor, and Lorestan. In the confrontation between the Ottoman Empire and Persia, the Kurdish provinces served as outposts of the two states, forcing various Kurdish tribes to be loyal to one or other of the powers and thus contributing to a potential conflict between the Kurds in the future.

After the Sykes–Picot Agreement, the Kurds were also divided between spheres of influence and, as regional countries gained independence, they were once again included as citizens of various states. Two attempts to create their own state in the 20th century were doomed to failure. In the 1920s, the self-proclaimed Kurdish Republic of Ararat in Turkish Kurdistan managed to exist for just three years, while the Republic of Mahabad in Iran, which was declared independent in 1946, lasted for less than a year.

External actors have used the Kurds for their own purposes. While Israel began supporting the Kurds because of its chronic inferiority complex (Ben Gurion’s expression) as a result of being surrounded by Arab countries (the same reason led to a close cooperation with the Shah’s regime in Iran until 1979), the US had other expectations and pragmatic strategies. Iraqi Kurdistan, for example, became a foothold for operations against Saddam Hussein in the 1990s and 2000s. Then the US deployed bases in the cities of Erbil, Kirkuk and Mosul and, after the appearance of ISIS, used the fight against terrorism to justify its presence. But this was solely to do with its military presence.

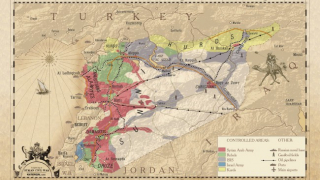

Ralph Peters’ infamous 2006 “blood borders” map of the Middle East shows Kurdistan as a monolithic state made up of parts of Turkey, Syria, Iraq and Iran, and reaching all the way up to the shores of the Black Sea in the north. Even earlier, the late British–American historian Bernard Lewis suggested a similar scenario – without access to the Black Sea (due to Turkey), but absorbing almost all of Armenia and a small portion of Azerbaijan. This version began to be developed at Princeton University back in 1981, where Bernard Lewis was a professor of Near Eastern Studies.

In practice, however, the issue of the Kurds getting a state of their own depends on two factors – 1) the political will of the Kurds themselves, which involves the elimination of internal conflicts and the development of a consolidated long-term strategy; and 2) the failed statehood of at least one of four countries – Syria, Iraq, Iran or Turkey.

But the ideal plan for an independent Kurdistan involves the unification of all four areas – Bakur, Başûr, Rojava and Rojhilat (literally – North, South, East, West), i.e., the Turkish, Iraqi, Syrian and Iranian territories inhabited by Kurds – but, in the modern world, such imaginary projects are usually far from being practically implemented.

Let’s look at each country individually in terms of the possibilities for building a Kurdish state.

Iraq

It is clear that the Iraqi Kurds, who have their own autonomy, had the best chance of building a state. Yet the author of this article, who has visited Iraqi Kurdistan many times, has never received a satisfactory answer as to how Iraqi Kurds see their future statehood. It is under discussion. Some see it as a broader autonomy, others suggest a republic type of government, and there are even some in favour of creating a monarchy.

The civil war that broke out in Iraqi Kurdistan in 1994 and ended in 1998 with a peace agreement mediated by the US and signed between Masoud Barzani (Kurdistan Democratic Party (KDP)) and Jalal Talabani (Patriotic Union of Kurdistan (PUK)) is also additional evidence of infighting among the Kurds. Although issues of internal self-government in Iraqi Kurdistan are now being resolved peacefully, the KDP still leans towards Turkey and, in part, the US, and the PUK towards Iran.

In addition to this, there are also cultural differences. The Kurds use different language dialects. Even in Iraqi Kurdistan, the Kurmanji and Soranî dialects are used, and there has recently been talk of a third dialect emerging based on a mixture of the two. There is also Southern Kurdish and Laki (both common in Iran and Iraq).

Syria

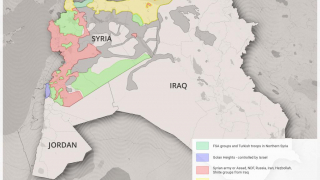

In Syrian Kurdistan (Rojava), the issue of self-government was raised fairly late – in 2012 – when Syria itself was under attack from both outside and from within. Around the same time, the People’s Protection Units (YPG) were created. Tensions immediately flared up with the Iraqi Kurds of the Barzani clan.

The Democratic Union Party (PYD), which consisted of local Syrian Kurds, and another group, the Kurdish National Union, which has links with the Kurdish regional government of Iraq, were unable to agree on the sharing of power, causing tension on the ground. The YPG even categorically objected to the entry of Iraqi Kurdish Peshmerga forces into Syria to help fight against ISIS. The PYD also accused Barzani of having links with the Turkish government and preferred to deal directly with the Kurdistan Workers’ Party (PKK) in Turkey.

The Democratic Union Party (PYD), which consisted of local Syrian Kurds, and another group, the Kurdish National Union, which has links with the Kurdish regional government of Iraq, were unable to agree on the sharing of power, causing tension on the ground. The YPG even categorically objected to the entry of Iraqi Kurdish Peshmerga forces into Syria to help fight against ISIS. The PYD also accused Barzani of having links with the Turkish government and preferred to deal directly with the Kurdistan Workers’ Party (PKK) in Turkey.

In March 2016, the Kurdish administration in three areas of northern Syria – Jazira, Kobanî and Afrin – announced the creation of the Federation of Northern Syria, Rojava. It was a clear attempt to unite separate geographical areas under a single political umbrella controlled by the PYD and its military units, the YPG.

In August, however, Turkey sent troops into Syria, creating its own security zone and starting a rapprochement with Russia. These developments undermined the efforts of the PYD and its allies, and the recent return of Syrian armed forces to the area and the Russian military police has severely limited any possibility of a genuine Kurdish sovereignty in Syria.

Turkey

Turkey is the country with the largest number of Kurds, both in terms of the general Turkish population and its territory. The PKK is recognised as a terrorist organisation in Turkey. Moreover, not all Kurds in Turkey agree with the party’s agenda and activities. Yet the ruling Justice and Development Party does not have an unbiased, inclusive policy for all Kurds. The rights of Kurds are defended by the Peoples’ Democratic Party (Halkların Demokratik Partisi). Essentially, it is a coalition of various left-wing parties and unions, including the Kurdish Peace and Democracy Party, and it is through this coalition that the Kurds legally lobby for their interests. Any attempts at separatism, however, or any hint of a link with the PKK are dealt with severely by the government. In 2016, the party’s Kurdish leaders, including Selahattin Demirtaş, were arrested on charges of supporting terrorists. Moreover, Ankara rejected the charges and demands of the ECtHR in this case. And, in August 2019, three of the party’s pro-Kurdish mayors were removed from their posts.

The operation by Turkish armed forces in Syria and the air strikes on Kurdish territories in northern Iraq, where the PKK’s bases are located, are evidence of Ankara’s serious intentions with regard to the consolidation of the region’s Kurds and the challenges they may pose to the Republic of Turkey.

Iran

Any Kurdish political structures are banned in Iran. The Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps keeps a close eye on any activity that is contrary to the form of government in, and ideology of, the Islamic Republic of Iran. Kurdish militants launch regular attacks on Revolutionary Guards and officials, and, in response, the authorities are forced to carry out reprisals. Kurdish political activists and dissidents from Iran have to hide in Iraqi Kurdistan. In Iran, any chance of even self-government for the Kurds is doomed to failure.

The Democratic Party of Iranian Kurdistan’s (PDKI) armed wing, known as the Iranian peshmerga, train near the Iran-Iraq border, May 13, 2017

The Democratic Party of Iranian Kurdistan’s (PDKI) armed wing, known as the Iranian peshmerga, train near the Iran-Iraq border, May 13, 2017

It also needs to be understood that any precedent related to the political strengthening of the Kurds will cause a backlash not just in the country concerned, but in neighbouring ones as well. Thus, the referendum held in Iraqi Kurdistan in September 2017 gave rise to protests not just in Baghdad, but also in Turkey and Iran, which are both sensitive to the issue of separatism.

And since the Kurds were unable to reach a compromise between themselves and create a semblance of a federation even when the situation in terms of the centralisation of power in Iraq and Syria was far worse, it is unlikely they will be given another chance in the near future. So, for many years yet to come, the idea of a Kurdish state will remain a longed-for, but unattainable, dream.