The Nomos Of Cybersecurity And A Sovereign Internet

The term “Nomos” was introduced into modern political science by the German lawyer Carl Schmitt. The word had several meanings in Ancient Greece, including “law” or “custom”. It was also an administrative territorial unit (divided into “nomoi”). Carl Schmitt used it to denote the principle of organising space. And with the advent of cyberspace, it is worth thinking about the division of this particular territory, given that maritime, air and land borders already exist. The space is unique because it is man-made, it can be altered, and it does not have clear borders. Although it is possible to clarify jurisdiction over the infrastructure used for the World Wide Web, there are still no internationally recognised rules governing behaviour in cyberspace itself.

This preamble is necessary for a more adequate understanding of the current state of the Internet and recent events related to it.

First: tests to make Russia’s infrastructure autonomous. Despite bold statements in the Western press about Russia trying to disconnect itself from the global Internet, there have been no moves in this direction. Similar tests have been carried out in the past and they had absolutely no effect on the Internet’s operation, for the majority of Internet users, at any rate. This attests to the effectiveness of measures designed to ensure the smooth operation of the Internet within Russia in the event of systemic cyberattacks or related political decisions directed against Russia by countries with a clear advantage in the governance of cyberspace.

Second: the threat of these cyberattacks. Pentagon officials publicly spoke about offensive operations in cyberspace back in February 2019. In the same month, US Cyber Command confirmed that its specialists had carried out a cyberattack against Russian infrastructure. In December 2019, meanwhile, the head of Cyber Command once again stated that, to prevent interference in the 2020 US presidential election, more cyberattacks would be carried out against the Russian Federation. In the dry language of the US Defense Department, it is “when authorized, taking action to disrupt or degrade malicious nation-state cyber actors ability to interfere in U.S. elections.”

Soldier in glasses of virtual reality. Military concept of the future.

General Paul Nakasone noted that Cyber Command would target “senior leadership and Russian elites, though probably not President Vladimir Putin, which would be considered too provocative.” An article in The Washington Post stated that the aim would be “sensitive personal data” that could be of some value. And it might not just be personal data. The capabilities of US Cyber Command, the CIA, the National Security Agency and other organisations that develop and use cyber tools for various purposes are constantly being improved. The budget increases every year, new departments and centres are established, and specialised competitions and events are held to recruit promising hackers.

Third, and directly related to the previous two points: the methods of information warfare used in cyberspace. Leading US technology companies whose products are available on the global market work closely with the White House and US State Department, fulfilling all political requirements. Blocking pages on social media, creating a stealth mode for Internet posts at odds with the ideologies of the US government and even deleting accounts have all become the kind of norm that your average American wouldn’t have dreamed of.

The fact is that social media in the US has long been used for advertising. This relates primarily to Facebook, which makes a lot of money out of it. But Facebook recently began blocking and even removing this advertising. Put another away, it took the money without providing the service. This resulted in a number of lawsuits being filed against Facebook. While it’s possible to seek compensation within the US or begin a public debate on the illegality of such methods, this is virtually impossible for people who live in other countries.

Looking at regional clusters, it is possible to see that blackouts are politically motivated. Take Georgia, for example, where hundreds of Facebook pages related to the country’s government were recently deleted. On 20 December alone, according to a statement by Nathaniel Gleicher, Head of Security Policy at Facebook, the company removed 39 accounts, 344 pages, 13 Facebook groups and 22 Instagram accounts. They were all registered in Georgia, so it was nothing to do with fake accounts. Facebook was simply confused by the usual kind of information related to local political events that was being circulated on these pages.

Facebook also removed 610 accounts, 89 pages and 156 groups in Vietnam and the US.

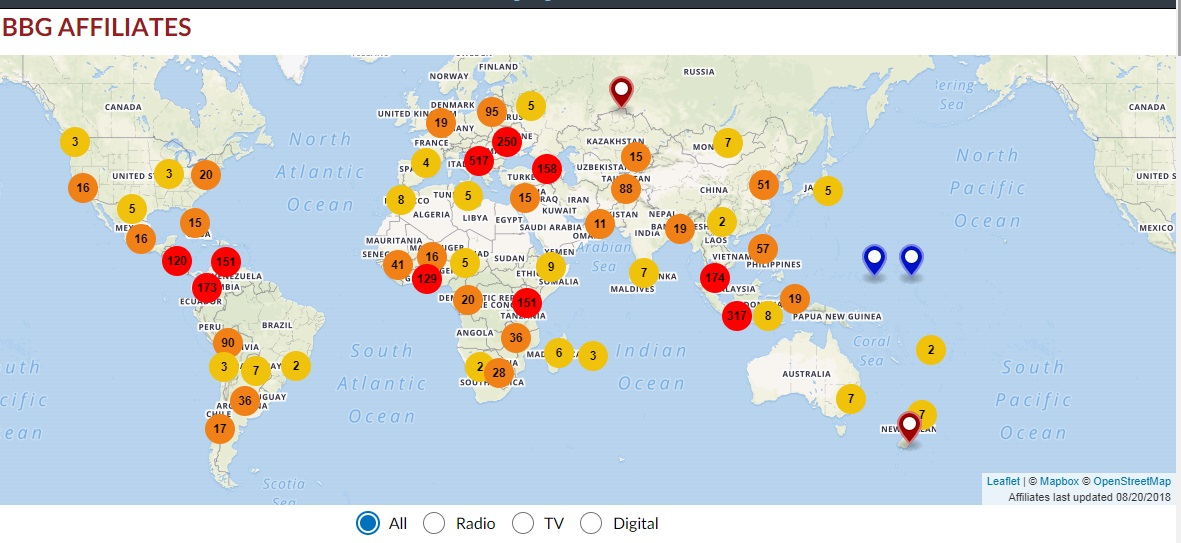

Yet the US Agency for Global Media (best known for its Radio Liberty/Radio Free Europe project) systematically circulates fake news, as well as finances and trains its agents abroad to generate propaganda on a new level and pursue US foreign policy through regional media outlets. There is a map on the agency’s old website showing the location of its offices around the world, a clear indication of which countries it covers.

In 2019, the agency launched a modernisation project that also seems to involve working with other US companies, the consequences of which we can see in the targeted information purges around the world.

Let’s not be naive and assume it will all work itself out or the issue will be peacefully resolved by the UN Internet Governance Forum. The West, and the US in particular, sees the Internet as a new frontier that has yet to be conquered. The pioneers of the cyber frontier represented by US Cyber Command and hired hackers will try to control this new Nomos both legally and by way of covert operations to introduce spyware, Web crawlers and Internet scanners.

With this in mind, testing the possibility of a sovereign Internet is a matter of fundamental importance that combines issues of national security, the performance of critical infrastructure, the combating of negative propaganda (not necessarily just political in nature but also cultural, which could nevertheless have far-reaching implications – outbursts of strange fads among the young, for example, that don’t fit in with social patterns of behaviour and often have a certain illegality to them), and the adequate performance of one’s own media space.

Source: OrientalReview