Distressed Farmer of Rising India

21.12.2020

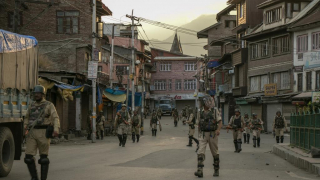

Indian farmers are resolutely protesting against a new legislation passed by the Narendra Modi’s government. The legislation enables farmers to sell their produce to any buyer and uplifted state-controlled markets’ commission agents. Set up in 1950s, these controlled markets ensured Minimum Support Price (MSP) – a safety net – to farmers thereby avoiding competition and exploitation by the multinational corporations. Scores of farmers especially small ones, in order to record their protest against new rules, have nearly sieged New Delhi – the capital of India. For dispersing agitated and frustrated farmers, Indian police and paramilitary forces are not leaving any stone unturned, not to mention the disproportionate reliance on the use of tear gas and water cannons during winter.

Why are Indian farmers opposing the legislation? The latest protest did not come out of blue but rather has a history in Indian politics. More than 50 per cent of workforce in India belongs to the agriculture profession but their wellbeing has been secondary to a food (in)secure India. The campaign for farmers’ rights started in May 1984 by Punjabi leaders under the slogan of ‘Punjab Bandh’ wherein they refused to deliver crops and pay taxes to the federal government. The then central government, in response, deployed 100,000 Indian army and paramilitary forces leading to Darbar Sahib (Sikh Holy Site) attack and assassination of India prime minister by her Sikh bodyguard.

Starting from there, agitation and turmoil in Punjab because of India’s human rights abuses (killings and disappearances) against Sikhs of Punjab resulted in thousands of civilian casualties. The central governments’ biased attitude towards the Sikhs of Punjab also germinated an armed uprising for self-determination.

Given above-mentioned brief history, the current protest is no less than a ticking bomb. The new law makes small farmers more vulnerable to the exploitative corporation and big farmers as they divest them from minimum price guarantees. Again, there is a historical context to the farmers’ protest and their lack of trust on the federal government. The 1966 famine in India led her to the ‘Green Revolution’ as well. Applying this technology in the fertile land of Punjab as a test case, the lands miraculously produced more crops in a limited time-frame. Though the sword of national famine was not there on the head of Indian government, it started a chain reaction economic and environmental degradation in Punjab, exacerbating conflict between farmers and the federal government.

Despite Green Revolution technologies, there is no profitable market for farmers to thrive as cost of production has exceeded from purchasing rate. As per a research report by Punjab Agriculture University, “eight out of ten farmers are in debt, and the average amount a farmer owes is more than four times the average annual income.” Moreover, the farmers were left at the mercy of multinational corporation. The incumbent Prime Minister of India, Mr. Narendra Modi in his election campaign promised to turn around the weary and teary situation on farmers. Instead, he reforms existing price guarantees for farmers with the agriculture reform bill. Because of new rules, small farmers will remain unable to sell its produce in comparison to the increased supply of big corporation thereby increased poverty and debt for small farmers.

Moreover, climate change-induced water scarcity, droughts, floods and uncertain weather patterns have also been impacting farmer. Punjab government report 2017 warned the extinction of groundwater in northern India by 2039. Because of bleak economic outlook, social insecurity, poverty and resulting psychological degradation, 10, 300 farmers took their life in 2019. According to a farmers’ organization, “Dozens more have committed suicide since the Modi government announced this legislation as ordinances in June.” As far as the environmental side of exploitation is concerned, India has been violating International Riparian Law by diverting Punjab’s water to non-agriculture states in the recent years. Resultantly, not only groundwater is diminishing but soil has been degraded as well whose cost has disastrous effects on farmers.

Indian farmers are very angry now. Barkha Dutt writes in the Washington Post, “there is broad national sympathy for the protests. The moral force of the Indian farmer cannot be underestimated.” In order to quench the grievances of farmers and end the impasse, the Indian government should repeal the new legislation and provide the farmers with MSP. Secondly, legislations that support sustainable agriculture practices and water and soil resource of Punjab, India should be respected. In this vein, the federal government should stop diverting water from Punjab rivers to non-agriculture parts of India. It would be safe to argue in the end that whether the Modi government will successfully cope with the crisis or not, it surely has damaged Mr. Modi’s reputation domestically, regionally and internationally.