Competition in global turbulence

Recently, a number of US think tanks have regularly published both small publications and rather lengthy analytical papers on global competition. This is not just about rivalry on the world stage, but about competition between the great powers, which the authors generally refer to as the US, Russia and China.

If we look at RAND's research, we see that they have published quite a few monographs on great power competition over the past few years. And while the latter were published in 2023, the research itself had begun years earlier.[1]

One such work states that competition in secondary theatres is likely to focus on historical centres of power. The influence of China and, to a lesser extent, Russia is increasing in secondary theatres, although the United States remains the dominant military player for the time being. However, it is stressed that the involvement of the great powers in conflicts in secondary theatres in the new era of competition may be less driven by zero-sum logic than was the case during the Cold War. This makes it difficult to assess the potential for conflict and its escalation.

It is even said that several plausible conflict scenarios could take place in Latin America, in which the United States could be involved on the side opposing Russia or China. Although there are no forces in this region that even declare intentions to confront Moscow and Beijing. An earlier paper states that the current rivalry between the major powers is fundamentally related to the nature of the international system. The US rivalry with China and Russia involves many overlapping military, economic and geopolitical interests and has significant implications for the international order. China in particular is working to change the dominant international rules, norms and institutions, in addition to enhancing its military capabilities. But the United States remains in a strong competitive position. However, its long-term success depends on maintaining a strong economic position and willingness to engage internationally; the disposition of key allies and partners; ideological influence on international rules, norms and institutions; and a strong global military posture vis-à-vis competing powers.[2]

Perhaps this imperative outlined by the authors explains the attempts that the US is making towards its allies, neutral countries and Russia's partners. It is no coincidence that there have been recent visits by US State Department delegations to Central Asian countries, where Kazakhstan and Kyrgyzstan are members of the EAEU. This also explains the announcement by Washington of new sanctions against Russia. And besides the main rivals of the US, their political planners prescribe areas of work and mark critical junctures on which they need to focus. Under the tag "geopolitical strategic competition," the RAND website generally gives quite a wide range of publications from the topic of the proxy war [3] and the conflict in Ukraine [4] to semiconductor manufacturing in Taiwan [5], changes in Japanese security policy [6] and outer space.[7]

It is clear that the US establishment is concerned about maintaining its global superiority and fears losing key positions in the global economy, logistics, financial and banking sector and the defence industrial complex.

The latter is particularly important for Washington, as the sale of weapons systems has several objectives - lobbying political groups associated with arms and equipment manufacturers such as Lockheed Martin, Boeing, Northrop Grumman and others, including the information technology sector (Amazon, Microsoft, Google); militarising states neighbouring target countries (such as Ukraine, Poland Finland); and dragging its satellites into pursuing its own interests, including new military and political strategies. U.S. attempts to bolster its military alliances can be traced in publications such as the UK's view on the above issues, where the need to engage with the U.S. is highlighted.[8]

The fact that the RAND Corporation works for the needs of the US military and receives funding from the Pentagon should be taken into account. But the overall view is of regions around the world and those areas where US (Western) interests conflict or potentially conflict with those of Russia, China, Iran, and a number of other countries (non-Western). Washington CSIS also highlights this theme, either thematically or regionally.[9]

In doing so, there is a noticeable overlay of labels that have been developed previously, such as "how does the United States respond to Beijing's grey area pressure tactics towards Taiwan and across the Indo-Pacific region as a whole? What is the best way to steadily deter Beijing from attacking Taiwan? Are there credible non-military tools that the United States and other like-minded countries can deploy?" On general global issues, questions are raised as to how the US can improve the sustainability and effectiveness of existing multilateral institutions (i.e. the model created by the collective West), and how best to use its economic weight to increase its influence in the Global South (and thus limit Beijing).[10]

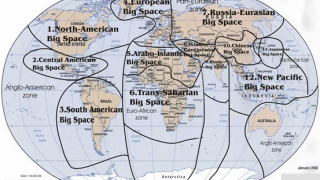

Apart from the fact that Washington is trying to maintain and further spread its influence across different regions, in fact, all this indicates a kind of consensus within the US establishment that a tri-polar world is coming, replacing the unipolar one.

The rise of two new poles, one representing the former superpower and the other boldly claiming active participation in governing world processes, is undermining the established model where the US was the main beneficiary. This model is often referred to in Washington as some kind of rules that were established by the collective West, and it is only natural that any reconfiguration threatens to reduce not only the flow of benefits on which the US and its satellites have parasitised, but also their importance as such. Because of this, the growing competition of the great powers is talked about from different positions (here Ukraine, Taiwan and other countries, but not only countries, but whole regions) in order to try to preserve their monopolies as much as possible and keep allies, partners and satellites in the orbit of their influence, without letting them take sovereign decisions and move to the other camp, even if it is conditionally neutral.

What draws attention is the fact that they are talking about states and not alliances. Although, the USA and NATO bloc is a whole regional military-political structure, which submerges whole states, separating them on cultural-historical grounds from their neighbours and certain meta-geographical spaces. Thus, Australia, New Zealand and even Japan and South Korea are usually defined as part of the collective West, although the latter two countries have their own distinctly Oriental identities. But the basic doctrinal documents of US foreign policy have not changed. The trend laid down under Barack Obama continues. Russia, China, Iran and the DPRK are identified as main threats to the US.

In this context, attention is drawn to Russia's new foreign policy concept, which not only changes the tone, but also uses different terminology, not characteristic of previous doctrines.

The general provisions already state that "Russia is a distinctive state-civilisation, a vast Eurasian and Euro-Pacific power that has united the Russian people and other peoples that make up the cultural-civilisational community of the Russian world. Although Nikolai Danilevsky wrote about cultural and civilizational types as early as the 19th century, this is presented here from a strategic position, as Russia is treated simultaneously as a European and Pacific power (a geographical factor) and as a Eurasian power (an ideological and cultural factor). It also claims that Russia "acts as one of the sovereign centres of world development and carries out its historically unique mission to maintain the global balance of power and build a multipolar international system, to ensure conditions for the peaceful, progressive development of humanity on the basis of a unifying and constructive agenda".

Obviously, this historic mission will be criticized by our detractors, as it has been repeatedly throughout history. Nevertheless, taking into account other emphases, such as the hope that the West will understand the futility of its policy towards Russia, as well as the interest in cooperation with different regions and associations, and designated countries among strategic partners, which is supported by concrete actions at the international level, it creates new conditions for interaction. And for the West, especially the US, this will be seen as a competitive challenge, including ideological issues.

This necessitates a more thorough and careful examination of those areas that are both highlighted in the concept and are already in the works. Because any weak points will be attacked by our geopolitical rivals. By and large, there is an additional demand for international experts in the relevant sectors and specialists in the regions and individual countries. Apart from the shift of professional staff from the collective West to other regions, as the Russian Foreign Ministry's leadership has previously stated, the launch of the second track of public-private partnership and public diplomacy will obviously qualitatively improve the work in this area from a long-term strategy perspective.

References:

1. Great-Power Competition and Conflict in the 21st Century Outside the Indo-Pacific and Europe

2. Understanding a New Era of Strategic Competition

3. Proxy Warfare in Strategic Competition: State Motivations and Future Trends

4. How the Ukraine War Accelerates the Defense Strategy

5. Supply Chain Interdependence and Geopolitical Vulnerability: The Case of Taiwan and High-End Semiconductors

6. Japan's New Security Policies: A Long Road to Full Implementation

7. Vanishing Trade Space: Assessing the Prospects for Great Power Cooperation in an Era of Competition — A Project Overview

8. Strategic advantage in a competitive age: Definitions, dynamics and implications

9. Allies and Geopolitical Competition in the Indo-Pacific Region ; U.S. and Iranian Strategic Competition