Alexander Dugin’s Neo-Eurasianism and the Eurasian Union Project: A Critique of Recent Scholarship and an Attempt at a New Beginning and Reorientation

A comprehensive analysis of the Eurasian Union project and its underlying political theory requires that closer attention be paid to the voluminous writings and academic activities of leading neo-Eurasianist Alexander Dugin than has been done heretofore. Reviewing the literature on Dugin and the Eurasian Union, I find that it lacks engagement with relevant primary sources. To establish this, I compare some of Dugin’s more recent works, unexplored in the literature, together with material from his lectures at Moscow State University, with the general consensus about him and his ideas. A gap emerges, indicating that the literature on Dugin needs to catch up with the literature by Dugin.

Introduction

The day after Vladimir Putin announced the goal of establishing a Eurasian Union between the Russian Federation, Belarus, and Kazakhstan, an important article appeared in the Financial Times. In that article, Charles Clover asserted that Putin’s announcement marked “the epitome” of the ambitions of “a small group of committed ‘Eurasianists,’” Alexander Dugin foremost among them. According to Clover, Dugin, head of the International Eurasianist Movement, even took credit for most of the content of Putin’s announcement at a conference at the University of Moscow the day the announcement came out, claiming to have helped in its preparation. Before leaving the topic of Dugin’s influence on Putin’s Eurasian Union project, Clover recalls John Maynard Keynes’s acute remark that “madmen in authority, who hear voices in the air, are distilling their frenzy from some academic scribbler of a few years back.” In this paper, I argue that a comprehensive analysis of the proposed Eurasian Union and its underlying political theory must pay more attention to the recent writings of the “academic scribbler” Alexander Dugin, the leading theorist of Eurasianism.

To support my argument, I examine a number of primary sources, including books, university lectures, and articles by Dugin, none of which are cited in the contemporary literature, and show how they enrich our understanding of Eurasianism. Then, I criticize a representative sample of English-language literature on Dugin for its lack of engagement with recent primary sources and correct misconceptions regularly occurring in that literature. Finally, I make the case that Eurasianism, on Dugin’s account, should be thought of primarily as a philosophical, rather than merely geopolitical doctrine.

The Fourth Political Theory: A Point of Orientation

Alexander Dugin is the author of over twenty books and ten textbooks on matters that should be of interest to any student of the Eurasian idea. Despite this, the select group of scholars who write about him only refers to a small number of his writings. This is partially forgivable on account of his prolific output, with which it is difficult to keep pace. Yet, any comprehensive understanding of Eurasianism will have to keep pace with his writings and take into account the theoretical developments that they contain. In this section, I examine two versions of Dugin’s book The Fourth Political Theory – the Russian version (2009) and English version (2012) – in order to discover what each has to teach us about contemporary Eurasianism. As far as I can tell, this book has not been referenced by the scholarly community in either the English or Russian versions, despite being available in Russian for two years.

In his most recent public statement, Dugin calls his notion of the Fourth Political Theory “perhaps the most vanguard sector of my scientific research [into] political philosophy.” Eurasianism, according to Dugin, can be thought of as “one of the preliminary versions of such a fourth political theory.” His book The Fourth Political Theory has been translated into English, Italian, French, Farsi, and numerous other languages, and the major English-language website promoting his thought refers to the concept in its web address (4pt.su). Lomonosov Moscow State University, where Dugin was the head of the Faculty of Sociology of International Relations and the founder of the Centre for Conservative Studies, used regularly to hold a range of conferences and workshops and issues publications devoted to the elaboration of the Fourth Political Theory. Accordingly, scholars of Eurasianism ought to study the idea of the Fourth Political Theory. Yet, very few scholarly articles reference it even superficially. Here, I shall offer a few observations on Eurasianism and the Fourth Political Theory in order to correct one of the most common misconceptions of Dugin’s thought in the literature.

A Critique of the Confusion of Conservatism with Fascism

The first prolonged discussion of Eurasianism in The Fourth Political Theory occurs in a chapter entitled “What is Conservatism?” In that chapter, Dugin distinguishes a number of kinds of conservatism, including traditionalism or fundamental conservatism, status-quo or liberal conservatism, the conservative revolution, and left-wing or social conservatism.

The first of these is characterized by its “rejection of the fundamental vector of historical development.” It is a view according to which “[t]he idea of progress is bad; the idea of technological development is bad; Descartes’ philosophy of the subject and object is bad; Newton’s metaphor of the watch-maker is bad; contemporary positive science and the education and pedagogy founded on it is bad” (2012, 87). Rene Guenon, Julius Evola, Titus Burckhardt, Leopold Ziegler and others are representatives of this form of conservatism (2012, 88).

It is worth observing that, according to Dugin, the association of fundamental conservatives with fascists is altogether wrong. On his account, “fascism is sooner the philosophy of modernity, which in a significant degree is contaminated with elements of traditional society, though it does not protest against modernity nor against time” (2012, 88). Thus, those who associate Dugin with traditionalism, traditionalism with fascism, and hence Dugin with fascism, err badly, in light of the Fourth Political Theory and would benefit from studying his disambiguation of Eurasian conservatism from both traditionalism and fascism.

As we shall see, accusations that Dugin is a fascist on other grounds ought also to be rethought in light of the theoretical distinctions of the Fourth Political Theory.

Status-quo or liberal conservatism consists of a “yes” said to modernity, mitigated by a desire to slow down or postpone “the end of history” (2012, 91-92). The liberal conservative seeks

to defend freedom, rights, the independence of man, progress, and equality, but by other [than leftist] means – through evolution, not revolution; lest there be, God forbid, a release from some basement of those dormant energies which with the Jacobins issued in terror, and then in anti-terror, and so on. (2012, 92)

Dugin mentions the German liberal thinker Jurgen Habermas as an example of a status-quo conservative, because of his fear of returning “to the shadow of tradition, the sense of the war against which was in fact represented by modernity” (2012, 92). Francis Fukuyama’s turn to nation-building as a stage on the way to democratic liberalizations also belongs here (2012, 91).

The Conservative Revolution holds the greatest philosophical interest for Dugin. To this school of conservatism belong such figures as Martin Heidegger, the Junger brothers, Carl Schmitt, Oswald Spengler, Werner Sombart, Othmar Spann, “and a whole constellation of mostly German authors, who are sometimes called ‘the dissidents of National-Socialism’” (2012, 94). These thinkers share the fundamental conservative critique of modernity, but wonder whether there was not something in the traditional state of affairs that implied its later destruction. From their perspective, a simple return to pre-modernity would not solve any problems, for it might be that “in the very Source, in the very Deity, in the very First Cause, there is laid up the intention of organizing this eschatological drama” (2012, 95). Hence, “[c]onservative revolutionaries want not only to slow down time (like liberal conservatives) or to return to the past (like traditionalists), but to pull out from the structure of the world the roots of evil, to abolish time as a destructive quality of reality” (2012, 95).

Finally, left-wing or social conservatism, as typified by Georges Sorel, maintains that the left and the right both fight the bourgeois as a common enemy. According to Dugin, this view has similarities to Ustralyov’s National-Bolshevism (2012, 98).

Eurasianism “concerns itself with the class of conservative ideologies.” It “shares some characteristics with fundamental conservatism (traditionalism) and with the Conservative Revolution (including…social conservatism…)” but rejects liberal conservatism (2012, 98-99). Analyses of Eurasianism as a political idea or political ideology will need to understand the ways in which it borrows from and incorporates the insights of various conservatisms, without erroneously concluding either that because it is conservative, it cannot be leftist or that because it is conservative, it must be status-quo or liberal conservative.

Most importantly, such analyses must avoid the confusion of calling Eurasian conservatism fascist. The basic logic of this error, simply put, runs as follows: Eurasianism is neither liberal nor communist, nor a variant of liberalism or communism. Therefore, it must be fascist. It is precisely against the claim that three political theories – liberalism, communism, and fascism – exhaust the options that the Fourth Political Theory has been announced. Accordingly, the surest antidote against such confusions consists in the study of Dugin’s political theoretic works, where the necessary distinctions are introduced.

A Critique of the Literature on Dugin as Civilizational Nationalist

The idea of civilization plays a distinctive role in Eurasian conservatism. According to Dugin, Eurasianism differs from the conservative ideologies it resembles in that “the alternative to modernity is not taken from the past or from a unique revolutionary-conservative revolution, but from societies historically co-existing with Western civilization, but geographically and culturally different from it” (2012, 99). Here, I shall not elaborate this aspect of neo-Eurasianism. Instead, I shall offer a brief criticism of recent literature on the topic.

The importance of the idea of civilization in contemporary Russian ideological discourse has been noted by such scholars as Verkhovskii. In a 2012 of Russian Law and Politics dedicated to “The Claim of Russian Distinctiveness as a Justification for Putin’s Neo-Authoritarian Regime”, Verkhovskii and others discuss the resurgence of the “age-old idea of Russia’s ‘special path’” (5) and, in particular, one version of it, which Verkhovskii calls “civilizational nationalism.”

Verkhovskii, who, incidentally, perpetuates the error of referring to Dugin as a “neo-fascist” (60), categorizes neo-Eurasianism as one type or “political current” of civilizational nationalism. Significantly, he states that “all the sections of Russian nationalism discussed above make use of [Dugin’s] ideas to some degree” (61). Unfortunately, he does not elaborate the specific ways in which various Russian civilizational nationalists draw on Dugin’s ideas. Instead, he is content to remark that the appointment of Dugin, “one of the most odious ideologues of civilizational nationalism” to a position at Moscow State University is evidence of the increasing influence of “the rhetoric of civilizational nationalism” in the academy (79).

Of course, Verkhovskii cannot undertake a serious and nuanced analysis of the idea of civilizational nationalism as elaborated by Dugin when he unjustly perceives Dugin as an “odious” “neo-fascist” and is already committed to a view of things in which it is a “dead end” to try to go “against the global tendencies of world development” (82), thus begging a central question against his interlocutors.

But the more serious problem, it seems to me, is not that Verkhovskii doesn’t like or agree with Dugin, or that he begs important questions against him, but that he doesn’t study him. If we accept with Verkhovskii that the “theoretical constructions of the radicals” - that is, the civilizational nationalists - are founded on three pillars: (1) that “a special Russian civilization exists,” (2) that “the natural territorial-political form of such a civilization is the empire,” and (3) that “the leading role in the empire must be played by ethnic Russians,” (58) and we further admit Dugin’s importance as the most theoretically sophisticated, relevant, and influential of the theorists of civilizational nationalism, then it would be irresponsible not to undertake a careful analysis of Dugin’s recent statements on those three pillars - civilization, empire, and ethnos - and instead rashly to rehash pronouncements of his “neo-fascism.”

After all, precisely the themes of civilization, empire, and ethnos play an important role in both the Russian and English versions of The Fourth Political Theory. In the English version, a chapter on “‘Civilisation’ as an Ideological Concept” runs twenty pages (Dugin 2012, 101-121). In the Russian version, in a chapter entitled Conservatism as a Project and Episteme, empire is given a robust philosophical defense and is articulated in a tri-partite structure consisting of space, narod, and religion, which itself is a reflection of the tri-partite structure of the conservative episteme: geopolitics, ethno-sociology, and theology. Part Three of the Russian version of the book bears the title The Geopolitical Context of the 21st Century: Civilization and Empire and features numerous chapters and sections on the question of civilization and Russian identity; for instance, the section called Russia as a Civilization (Cultural-Historical Type) and the two chapters Carl Schmitt’s Principle of ‘Empire’ and the Fourth Political Theory and The Project ‘Empire.’ In Part Five of the Russian edition of the book (available, I repeat, since 2009), Dugin discusses “the formula of Russia’s socio-genesis”, including specifically the elements of “the ethnic constant” and “the ethnic variable”, structurally distinguishing not only constants and variables, but also the ethnos from the narod.

In short, even the most recent literature on the topic of Dugin’s neo-Eurasianism as a type of new Russian ideology fails to consider the relevant primary source materials, in which all the pertinent theoretical categories are elaborated in detail. This failure stems in part, it seems to me, from an apriori anti-Duginism, which itself arises, in part, from the loaded judgement that Dugin is a “neo-fascist.”

I must therefore repeat that scholars of Dugin and neo-Eurasianism should set aside their prejudices, consult recent primary source material, and be guided in their analyses, at least preliminarily, by Dugin’s own theoretical distinctions. Perhaps these scholars can then find rationally defensible grounds on which to contest Dugin’s thoughtful positions, rather than resorting to the kinds of hasty mischaracterizations Laruelle warned about.

A Critique of the Literature on Dugin’s Neo-Eurasianism

Besides references to Dugin in general surveys of resurgent Russian nationalism, research dedicated to Dugin’s neo-Eurasianism itself also exists in English-language scholarship. For instance, the Jan/Feb 2009 issue of the journal to which I have been referring, Russian Politics and Law, was devoted to an analysis specifically of Dugin’s neo-Eurasianism. How does that research fare in terms of citing Dugin’s (then) recent primary sources?

Leonid Luks’ article A “Third Way” – or Back to the Third Reich? discusses the picture of Eurasianism that emerges from a reading of articles in the early journal Elements, edited by Dugin. The guiding question of the article is whether the self-proclaimed Eurasianism of the authors of Elements in fact represents the legacy of the classical Eurasianists (8). Surprisingly, although the study does not cite any articles or books written after 1995, Luks writes of the thoughts of the editors of Elements about “present-day theories of globalization [and] the one-world model” (8). Since his study was written in 2009, it is curious that Luks takes comments from 1993-1995 as current appraisals of “present-day theories.”

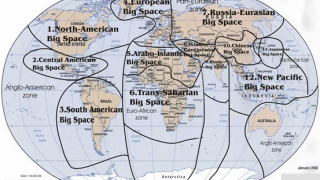

Luks’ study, which concludes that the Eurasianism of Elements has more in common with the Weimer conservative revolutionaries than with the classical Eurasianists, is, as is the journal issue as a whole, an important, if alarmist, contribution to the study of neo-Eurasianism. But because it fails to refer to more recent developments in Dugin’s neo-Eurasianism, a number of its analyses miss the mark. For instance, Luks writes that Elements sets against the unipolar American conception of the world “a bipolar conception based on a new conflict between East and West” (20). But a correct understanding of neo-Eurasianism today would surely have to focus not on bipolarity, but on multi-polarity. Because Luks did not take account of the more than twenty or so books that Dugin published between 1995, the date of the last article Luks quotes, and 2009, the year in which his own article came out, it is difficult to see the value in his sweeping generalizations about the Hitlerist implications of today’s neo-Eurasianism on the basis of Elements articles from 1993-1995.

Laruelle’s article does not cite any of Dugin’s works written after 1997, though she does refer to some of her own writings on Dugin, and to Dugin’s 2004 The Eurasian Mission of Nursultan Nazarbayev, “brought out by the Moscow publishing house Evraziia, printed on glossy paper, and probably financed by Astana” (99). Unfortunately, a similar failure to reference recent writings also detracts from the general implications of Umland’s article. Sokolov’s article New Right-Wing Intellectuals in Russia, does not cite Dugin even once and does not go farther in engaging with his works than merely naming two of them (66). Following this trend, Senderov cites only one of Dugin’s books, Foundations of Geopolitics, and only once. Thus, in an issue dedicated to “the Dugin phenomenon” (4), what is most phenomenal is the scantiness of reference to Dugin’s own writings.

Contemporary Eurasianism: More than Geopolitics

One of the shortcomings of literature on neo- or contemporary Eurasianism is its one-sided emphasis of geopolitical questions and its consequent undervaluation of other elements of that doctrine or approach. According to Dugin, neo-Eurasianism accepted the main points of the worldview of the Eurasian thinkers of the 20s and 30s, but “supplemented them with attention to traditionalism, geopolitics, structuralism, the fundamental-ontology of Heidegger, sociology, and anthropology” (2012, 100). But from what I have been able to discover, almost all of the significant English-language scholarship on Dugin has focused on his geopolitical writings, to the exclusion of the other components of neo-Eurasianism listed by Dugin, with a few noteworthy exceptions.

A comprehensive account of neo-Eurasianism will have to include the philosophical, sociological, anthropological and other elements of that approach and understand how they interact. Previous accounts of Dugin’s thought should be revised to correspond to a more accurate and up-to-date description of neo-Eurasianism. For instance, Laruelle’s contention that Dugin “does not find congenial” the philosophy of Martin Heidegger (2006, 18) must be abandoned, now that Dugin has written four books about Martin Heidegger and refers to him as providing the deepest foundations for the Fourth Political Theory and for the possibility of a distinct Russian philosophy.

In this section, my goal is to offer a brief sketch of Dugin’s “neo-Eurasian episteme” as he describes it in the Russian and English versions of The Fourth Political Theory and to make a few observations on the role of Heidegger’s thought for Dugin. The purpose of this section is to contribute to an understanding of Dugin’s thought that is not marred from the outset by a prejudice against it, by a failure to consult recent primary sources, or by a narrow focus on geopolitics.

The necessity for such an undertaking increases daily. Yigal Liverant’s perceptive remark that “there is an undeniable connection between Dugin’s politics and the regime change led by Putin,” his correct contention that “Dugin and his philosophy cannot…be dismissed as an insignificant episode in Russian intellectual history…[but rather] reflect the dominant trend in current Russian politics and culture” and his prediction that “their influence over the general public and decision makers in the Kremlin is only going to become stronger” (52) deserves attention. Putin’s request to be received at the 2012 EU-Russia summit as the representative of the Eurasian Union and the spat caused by US Secretary of State Hillary Clinton when she remarked that the US knows “what the goal is” of the Eurasian Union and is “trying to figure out effective ways to slow down or prevent it” both testify to the ongoing relevance of the Eurasian idea and project in understanding the Russian of the early 2010s, and hence also to the importance of its leading theorist and visionary.

The Eurasian and Conservative Epistemes

Dugin refers to Eurasianism not as a political philosophy but as an “episteme” (2012, 98). An episteme, according to the philosopher whom Dugin follows here terminologically, is a “strategic apparatus which permits of separating out from among all the statements which are possible those that will be acceptable within, I won’t say a scientific theory, but a field of scientificity, and which it is possible to say are true or false” (Derrida, 1980). If the “modern episteme” is dominated by modern, mathematical, natural science and the “post-modern episteme” by the “linguistic turn” and the “deconstruction” of texts and power relations, what characterizes the Eurasian episteme, on Dugin’s account?

The “specific character” of the Eurasian episteme is its refusal to consider the “Western logos” as inevitably universal (2012, 99). Eurasianism “considers Western culture as a local and temporary phenomenon and affirms a multiplicity of cultures and civilizations, which coexist at different moments of a cycle” (ibid). Because there is “no single historical process” and “every nation has its own historical model, which moves in a different rhythm and at times in different directions”, the Eurasianist can assert that “modernity is a phenomenon peculiar only to the West” and call on others to “build their societies on internal values,” rejecting the West’s claim to the universality of its civilization (ibid). Thus, Eurasianism opposes to the “unitary episteme of modernity” a “multiplicity of epistemes, built on the foundations of each existing civilization” (ibid).

Neo-Eurasianism takes this Eurasianist view of modernity and gives it a “philosophical analysis” (2012, 100), specifically in terms of its temporal dimension. Philosophically, it articulates a rejection of the notion of “unidirectional time” (ibid; see also 55-67). In the view that it criticizes, time proceeds from past to future through the present and is considered not from the standpoint of being, but from that of becoming, of movement forward. The conception of the conservative as one who is trying to retrieve a past moment from a linear progression of time thus presupposes a unidirectional concept of time, which the neo-Eurasianists reject on philosophical grounds.

This notion of an alternative temporality is not irrelevant to the political consideration of neo-Eurasianism. Some critics of neo-Eurasianism accuse it of being nothing more than a program to return to the glorious days of the Soviet Union. Recently, for instance, US Secretary of State Hillary Clinton asserted that the Eurasian Union project is a “move to re-Sovietize the region”, thus conceiving of the new project as a return to the past. Similarly, the Telegraph ran a story about the Eurasian Union in in 2011 entitled “Vladimir Putin is trying to take Russia back in time.” Some commentators have quipped that the Eurasian Union hearkens a movement “Back to the USSR.” Others might plausibly interpret such a move as “turning back the clock,” i.e. returning to a time before the enlightenment of political life through the doctrines of liberalization, Westernization, and human rights.

But because the neo-Eurasianist conservative is not someone who wants to recover a lost past from a unidirectional temporal history, criticisms of the neo-Eurasianist project that view it in unidirectional temporal terms fail to understand it in its own terms. Only by begging the question of temporality against the neo-Eurasianist from the outset is it possible to view his project as in some sense “retrograde” (2010, Chapter Six). After all, Russia has many incompatible moments in its history, making the notion of the conservative as one who wants to return to the past, in Russia, at least, inconsistent and contradictory. As Dugin puts it, “[w]hen a conservative turns over the pages of a book of Russian history, he sees in it both golden and abominable pages,” including “much…that is categorically unacceptable and anomalous for a consistent Russian conservative” (ibid).

Rather than unidirectional temporality, the neo-Eurasian conservative operates with a “synchronic model” of time (ibid). On this model, the conservative “does not fight for the past, but for the constant, the perennial, that which essentially always remains identical to itself” (ibid). Past, present, and future are modalities to which one can be oriented, but what is important in them is what is constant in them.

To explain his view of temporality, Dugin relies on a formulation he later elaborates in his first book on Heidegger. According to this formulation, the merely temporal categories of past, present, and future are not what interest the conservative thinker. Instead, that which has been, that which is, and that which will be commands his attention. In other words, not “empty time” but being as it was, is, and shall be, being as constant but under different modalities, commands the attention of the conservative thinker. “If”, Dugin writes, “for ‘progressives’ and the followers of the philosophy of history being is a function of becoming (of history, time), then for the conservative…time (history, duration, Zeit) is a function of being.” For “being is primary, time is secondary” (ibid).

This orientation towards being as constant underlies the neo-Eurasian critique of other “conservative” projects in today’s Russia. These projects are “conceptually and philosophically on the wane, weak and superficial” because they lack “the most important thing…the breath of eternity” (ibid). They “imitate” liberals and “attempt to impart to conservative ideas a catchy and marketable package”, whereas true philosophical and ontological conservatism ought to avoid such approaches and instead seek to demonstrate “the irresistible truth of eternity” “by any means” and “at any price” (ibid).

Critics, however, might retort that Dugin’s own neo-Eurasian conservative project is among the best marketed of all Russian conservatisms (see for instance the well-produced and as it were well-packaged and well-marketed videos of Dugin’s university lectures, the catchy and marketable look of the websites evrazia.info, evrazia.org, evrazia.tv, konservatizm.org, platonizm. ru, granews.info, and so on) and wonder whether eternity’s concession to the importance of marketing does not constitute a price Dugin is willing to pay for the broad and effective adoption of his ideas. Nevertheless, the unusual philosophical character and ontological emphasis of Dugin’s neo-Eurasianism likely does set it apart from other conservative Russian movements (for instance Panarin’s) and bestow a different character on its “packaging.”

Dugin blames the failure of Russian conservatism on Russia’s “epistemological deficit.” Both the communist period and the period of liberalization that followed it were premised on the superiority of becoming to being and imbued the humanitarian sciences, and education foremost among them, with a scientific worldview established “on the explicit negation of eternity” (ibid).

Crucially, Dugin maintains that the project of implementing conservative policies is a secondary question, preceded by the task of elaborating a “preliminary system of coordinates”, “a sort of new, expressly conservative (ideologically, not methodologically) sociology, which is ready to perform the gigantic work of wide revisions of scientific, humanitarian and sociological conceptions” (ibid). Eurasianism as a political project thus depends the elaboration of an ideologically and ontologically conservative sociology, meant to replace the liberal and communist epistemes – this is the work taking place at MSU and elsewhere.

Although The Fourth Political Theory is but an invitation to contribute to the elaboration of such an episteme, Dugin does provide some specific suggestions as to how it should be developed. It should be “based on trichotomy” (ibid), both at the general level and at the particular level. For instance, at the general level, the conservative episteme consists of theology, ethnosociology, and geopolitics, analogous to man’s spirit, soul, and body (ibid). At the particular level, Empire should be analyzed in terms of religion, the narod and the territorial space, also on analogy with man. This episteme should replace the dominance of the liberal emphasis on jurisprudence and economics (ibid). For it is not that “economics is serious” and “theology is optional”, but “strictly the other way around”: “He who knows eternity knows everything. He who knows the temporary material regularities of the circulation of money, merchants, and goods does not even know that which he supposes himself to know” (ibid).

The idea of a specifically Eurasian educational and scientific paradigm meant to correct the inadequacies of the predominant liberal paradigm has important implications for the study contemporary Eurasianism. For instance, although commentators have noticed that a mystical view of the world implicitly underlies Dugin’s geopolitical writings, lacking the key of the “conservative episteme”, they have not been able to give a proper account of why Dugin should see geopolitics in light of spirituality. Talk of empire as sacred is not simply poetic metaphor; it is in accordance with the axioms of the conservative episteme, where every phenomenon is seen in light of its fundamental ontological significance.

In short, because “the necessary condition for the working out of a full-fledged conservative project” is “the implementation of the conservative episteme” (ibid), as Dugin contends, analysts of the former – the Eurasian Union – ought surely to pay some attention to latter, to the conservative episteme as it is worked out by Dugin and others at Lomonosov Moscow State University in books, journals, and articles. Indeed, as Dugin indicated in an interview on Voice of Russia, Putin’s plans for a Eurasian Union are “unintelligible” and “unfeasible” outside of the broader context of the Eurasian political philosophy.

Conclusion

So far, I have argued that contemporary scholars of neo-Eurasianism and the Eurasian Union project have failed to pay due attention to the recent writings of the leading theorist of neo-Eurasianism, Alexander Dugin. In order to begin to remedy that situation, relying on the English and Russian versions of his book The Fourth Political Theory, I discussed Dugin’s conception of neo-Eurasianism as a form of conservatism and sought to correct the common error of referring to Dugin as a neo-fascist. Then, I showed that many of the themes of interest to these scholars – for instance, civilization, empire, and ethnos – are treated extensively by Dugin in recent books, which none of them have referenced; thus further supporting the claim that there is much to be gained by turning to consider primary sources. I suggested that the failure to do so stems from an apriori anti-Duginism, which itself involves begging the relevant questions against Dugin from a liberal, progressive viewpoint. In order to combat such an approach, I felt it necessary to discuss the notion of a “conservative episteme.” according to which the neo-Eurasianism and the Eurasian Union project should be understood and evaluated before a liberal critique is undertaken. Finally, I defended the view that neo-Eurasianism should be thought of primarily as a robust political philosophy and serious alternative to the liberal and communist intellectual paradigms, rather than as merely a geopolitical doctrine, demonstrating that Dugin himself presents it as such.

Hopefully, as a result of the arguments I have made, scholars of post-Soviet studies with an interest in neo-Eurasianism and the Eurasian Union project will begin to pay greater attention to Dugin’s prolific output and to the work of the think-tanks he has founded, such as the Center for Conservative Studies at Lomonosov Moscow State University and will modify their previous assessments of Dugin and his project in light of those recent writings, such as I showed was necessary to do in the case of Laruelle’s assessment of the relevance for Dugin of Heidegger. Secondly, I hope to have made a plausible case that the study of neo-Eurasianism should be undertaken not only in the context of post-Soviet studies, but also as part of the study of comparative political theory and political philosophy, alongside other critiques of and alternatives to modern liberal-democratic thought.

If I have achieved either of these aims in part, my task will have been accomplished.

***

Bibliography/Works Cited

Clover, Charles. “Dreams of the Eurasian Heartland: The Reemergence of Geopolitics.” Foreign Affairs 78, no. 2 (March 1, 1999): 9–13. doi:10.2307/20049204.

———. “Putin’s Grand Vision and Echoes of ‘1984’.” Financial Times. Accessed December 15, 2012. http://www.ft.com/cms/s/2/2917c3ec-edb2-11e0-a9a9-00144feab49a.html#axzz2F8GYs0wY.

Cummings, Sally N. “Eurasian Bridge or Murky Waters Between East and West? Ideas, Identity and Output in Kazakhstan’s Foreign Policy.” Journal of Communist Studies and Transition Politics 19, no. 3 (2003): 139–155.

Dugin, Alexander G. Martin Khaidegger: Filosofiya Drugovo Nachalo. Academic

Project, 2010. (in Russian).

———. Chetvertaya Politicheskaya Theoria. Amfora, 2009. (in Russian).

———. The Fourth Political Theory. Arktos, 2012

Dunlop, John B. “Aleksandr Dugin’s ‘Neo-Eurasian’ Textbook and Dmitrii Trenin’s Ambivalent Response.” Harvard Ukrainian Studies 25, no. 1/2 (April 1, 2001): 91–127.

Gromyko, Alexei. “Civilizational Guidelines in the Relationship of Russia, the European Union, and the United States.” Russian Politics & Law 46, no. 6 (December 2008): 7–18.

Hagen, Mark Von. “Empires, Borderlands, and Diasporas: Eurasia as Anti-Paradigm for the Post-Soviet Era.” The American Historical Review 109, no. 2 (April 1, 2004): 445–468.

Laqueur, Walter. Fascism: Past, Present, Future. New York: Oxford University Press, 1996.

Laruelle, Marlène. “(Neo-)Eurasianists and Politics.” Russian Politics & Law 47, no. 1 (February 2009): 90–101.

———. “Aleksandr Dugin: A Russian Version of the European Radical Right?” Kennan Institute Occasional Paper, no. 294 (2006): 1-26.

Libman, Alexander, and Evgeny Vinokurov. Eurasian Integration: Challenges of Transcontinental Regionalism. Palgrave Macmillan, 2012.

Luks, Leonid. “A ‘Third Way’--Or Back to the Third Reich?” Russian Politics & Law 47, no. 1 (February 2009): 7–23.

Makarov, V. G. “Pax Rossica: The History of the Eurasianist Movement and the Fate of the Eurasianists.” Russian Studies in Philosophy 47, no. 1 (July 1, 2008): 40–63.

Raskin, D. I. “Russian Nationalism and Issues of Cultural and Civilizational Identity.” Russian Politics & Law 46, no. 6 (December 2008): 28–40.

Richardson, Paul. “Russia in the Asia-Pacific : Between Integration and Geopolitics” (February 16, 2012). http://scholarspace.manoa.hawaii.edu/handle/10125/22210.

Rossman, Vadim. "V poiskakh russkoi idei: platonizm i neoevraziistvo," Forum noveishei vostochnoevropeiskoi istorii i kul'tury, vol. 6, no. 1 (2009): 57-77

Rukavishnikov, Vladimir. “The Bear and the World: Projections of Russia’s Policy After Putin’s Return to Kremlin in 2012.” Medjunarodni Problemi 64, no. 1 (2012): 7–33.

Rywkin, Michael. “Russian Foreign Policy at the Outset of Putin’s Third Term.” American Foreign Policy Interests 34, no. 5 (2012): 232–237.

Saivetz, Carol R. “The Ties That Bind? Russia’s Evolving Relations with Its Neighbors.” Communist and Post-Communist Studies no. 0. Accessed November 13, 2012. doi:10.1016/j.postcomstud.2012.07.010.

Sakolov, Mikhail. “New Right-Wing Intellectuals in Russia.” Russian Politics & Law 47, no. 1 (February 2009): 47–75.

Sedgwick, Mark. Against the Modern World. Oxford University Press, 2004.

Senderov, Valerii. “Neo-Eurasianism.” Russian Politics & Law 47, no. 1 (February 2009): 24–46.

Shekhovtsov, Anton, and Andreas Umland. “Is Aleksandr Dugin a Traditionalist?‘Neo-Eurasianism’ and Perennial Philosophy.” The Russian Review 68, no. 4 (2009): 662–678.

Shlapentokh, Dmitry. “Dugin, Eurasianism, and Central Asia.” Communist and Post-Communist Studies 40, no. 2 (June 2007): 143–156.

Shlapentokh, Dmitry V. “Eurasianism: Past and Present.” Communist and Post-Communist Studies 30, no. 2 (June 1997): 129–151.

Shnirel’man, V. A. “The Idea of Eurasianism and the Theory of Culture.” Anthropology & Archeology of Eurasia 36, no. 4 (April 1, 1998): 8–31.

Shnirelman, Viktor. “The Fate of Empires and Eurasian Federalism: A Discussion Between the Eurasianists and Their Opponents in the 1920s.” Inner Asia 3, no. 2 (2001): 153–173.

Spillius, Alex. “Vladimir Putin Is Trying to Take Russia Back in Time.” Telegraph.co.uk, October 5, 2011, sec. worldnews. http://www.telegraph.co.uk/news/worldnews/europe/russia/8808712/Vladimir-Putin-is-trying-to-take-Russia-back-in-time.html.

Tsygankov, A.P. “Mastering Space in Eurasia: Russia’s Geopolitical Thinking After the Soviet Break-up.” Communist and Post-Communist Studies 36, no. 1 (March 2003): 101–127.

Tsygankov, Andrei P. “Hard-line Eurasianism and Russia’s contending geopolitical perspectives.” East European Quarterly 32, no. 3 (Fall 1998): 315–334.

Tsygankov, Andrei P., and Pavel A. Tsygankov. “National Ideology and IR Theory: Three Incarnations of the ‘Russian Idea’.” European Journal of International Relations 16, no. 4 (December 1, 2010): 663–686.

Umland, Andreas. “Issues in the Study of the Russian Extreme Right.” Russian Politics & Law 47, no. 1 (February 2009): 4–6.

———. “Pathological Tendencies in Russian ‘Neo-Eurasianism’.” Russian Politics & Law 47, no. 1 (February 2009): 76–89.

Verkhovskii, Aleksandr, and Emil Pain. “Civilizational Nationalism.” Russian Politics & Law 50, no. 5 (October 2012): 52–86.

“Bulgaria and the Eurasian Union: Back to the USSR? - Paperblog.” Paperblog. Accessed December 20, 2012. http://en.paperblog.com/bulgaria-and-the-eurasian-union-back-to-the-ussr-257378/.

“Civilization as Political Concept.” Accessed December 18, 2012. http://4pt.su/en/content/civilization-political-concept.

“EU to Become Russia’s Priority in Foreign Policy.” Accessed December 20, 2012. http://www.presstv.ir/detail/2012/12/20/279090/eu-to-become-russias-priority-in-foreign-policy/.

“Globalist Mouthpiece Hillary Clinton Attacks Russia, Eurasianism.” The Green Star. Accessed December 18, 2012. http://americanfront.info/2012/12/07/globalist-mouthpiece-hillary-clinton-attacks-russia-eurasianism/.

“Neo-Eurasianism and Putin’s ‘Multipolarism’ in Russian Foreign Policy.” Accessed December 20, 2012. http://www.academia.edu/1048384/Neo-Eurasianism_and_Putins_Multipolarism_in_Russian_Foreign_Policy.

“Putin’s Eurasian Union: A Promising Development.” EurActiv.com. Accessed December 20, 2012. http://www.euractiv.com/europes-east/putin-eurasian-union-just-union-analysis-516749.

“Russia and the U.S. Spar Over Eurasian Union.” Accessed December 12, 2012. http://www.stratfor.com/video/russia-and-us-spar-over-eurasian-union.

Evraziiskii Soyuz: Stabil’nost’, Bezopasnost’, Protzvestanie I Suverenitet.

Www.russkie.org. Accessed December 20, 2012. http://www.russkie.org/index.php?module=fullitem&id=27967.