A sovereign state creates money. Otherwise, it is a colony

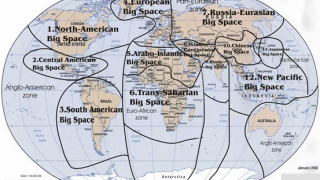

It is necessary to leave the unipolar system and, above all, its constructs to enter a new multipolar order, so that each state can regain its sovereignty and have its own weight in the contemporary geopolitical framework

One of the economic models that has greatly influenced the thinking of many economists is the IS-LM model, formulated by Sir John Richard Hicks to synthesise Keynesian economics and reabsorb it into the neoclassical fold. Without delving too much into technicalities, it is good to keep in mind that the IS-LM model consists of two functions: the IS, the set of equilibrium points of the goods and services market, characterised by the equality between investments (I) and savings (S); and the LM, representing the money market. In the first case, we have flow quantities, in the second stock. And already this should raise some questions, but the elephant in the room is another.

Mr Hicks, as a good neoclassic (liberalist), assumed that an increase in government spending would simply divert funds from the private sector to the treasury, depressing investment. Given the inverse relationship between investment and interest rate, the IS curve has a negative trend. If the interest rate rises, investment falls. And this is true. But investment is also influenced by income growth (accelerator theory). Nobody would invest (i.e. increase their productive capacity) if there was no demand, even if interest rates were low. This means that the model does not take due account of the marginal propensity to invest relative to disposable income. Otherwise, if it took this propensity into due account, the slope of the IS curve, instead of being negative, could be positive, with important consequences for economic policy. The marginal propensity to invest relative to disposable income may, in fact, be higher than the sensitivity of investment to the interest rate.

What is often blamed on the supporters of Keynesian policies is the crowding out effect, whereby increasing government spending would reduce the amount of investment, which would be discouraged by the rise in interest rates caused by government spending. In short: government spending increases the demand for money by the government, causing interest rates to rise and these would depress investment. This means that, given the money available in the system, the government, like households and businesses, would be an additional user of money - and therefore a competitor - rather than a creator of money.

For liberalists, the money supply is exogenous, that is, it is a constraint to which the government must also be subject. Therefore, before spending, the government must rake in money through taxes, impoverishing households and businesses. These dynamics, however, only affect a depowered state, that is, a colony state or an EU member state. A sovereign state, on the other hand, is a creator of money with a view to full employment, not a user of money. In light of this, if we examine financial flows, we will understand how an increase in public spending does not reduce private investment but increases it. When a sovereign state demands goods and services from the non-governmental sector (households and businesses), it transfers money (created ad hoc), which is a state liability, in return. This means that the government transfers funds to the current accounts of households and businesses, injecting money into the banking system. An increase in the money supply in the system can do nothing but reduce interest rates, as well as pushing up consumption, reducing the risk of unsold goods for businesses and, therefore, increasing their marginal propensity to invest relative to income. The problem, therefore, is not a rise in rates but a fall in them, which can be averted by issuing public debt securities. By issuing securities, the government transforms part of the 'liquid' money into money that pays interest (government bonds), thereby supporting interbank rates. In this way it can continue to spend towards full employment, controlling inflation.

A few decades after the publication of the article "Mr. Keynes and the Classics" (1937), Sir John Richard Hicks distanced himself from his model, henceforth signing himself J. Hicks and no longer J.R. Hicks. He wrote:

"It is clear that I must change my name. Let it be clearly understood that Value and Capital (1939) is the work of J. R. Hicks, a now deceased 'neoclassical' economist; while Capital and Time (1973) - and A Theory of Economic History (1969) - are the work of John Hicks, a non-neoclassical rather disrespectful to his 'uncle'. These latter works must be read independently and not interpreted, as Harcourt does, in the light of their predecessor' [John Hicks (1975) Revival of Political Economy: The Old and the New, Economic Record, 51 (135), 365-367].

"The IS-LM diagram, which is widely, but not universally, accepted as a convenient synopsis of Keynesian theory, is something for which I cannot deny that I am partly responsible. The diagram first saw the light of day in an article of mine, 'Mr Keynes and the Classics' (1937), but it was actually written for a meeting of the Econometric Society in Oxford in September 1936, just eight months after the publication of The General Theory (Keynes, 1936). However, I made no secret of the fact that, as time passed, I myself became dissatisfied with it. In my contribution to the Festschrift for Georgescu-Roegen, I said that 'that diagram is now much less popular for me than I think it still is for many other people'".

[John Hicks (1980) IS-LM: An Explanation, Journal of Post Keynesian Economics, 3:2, 139-154].

Although Hicks humbly distanced himself from his synthesis, it still remains a role model in many universities, generating the illusion that government intervention in the economy displaces investment and is therefore to be avoided like the plague.

The other elephant in the room is the notion that money supply is defined exogenously, when in fact it is created endogenously by the banking system. In 2014, the Bank of England published a very interesting article in its Quarterly Bulletin entitled: Money creation in the modern economy. On that occasion, the Bank's Monetary Analysis Directorate unequivocally dispelled any misgivings about the creatio ex nihilo of money, downplaying the fable of the money multiplier.

"In the modern economy, most money takes the form of bank deposits, but how these deposits are created is often misunderstood: the main route is through commercial banks making loans. Every time a bank makes a loan, it simultaneously creates a corresponding deposit in the bank account of the borrower, so that new money is created. The reality of how money is created today differs from what is reported in some economics texts. Rather than banks receiving deposits - when households save - and then lending them out, it is bank lending that creates deposits. In normal times, the central bank does not determine the amount of money in circulation, nor is central bank money multiplied into more loans and deposits'. (McLeay, M., Radia, A., Thomas R., Money creation in the modern economy, in Bank of England Quarterly Bulletin, 2014 Q1, Volume 54 No. 1, p. 14)

Removing the two elephants from the room is a necessary but not sufficient condition. One must, in fact, not only become aware of things but also regain the freedom to be able to decide one's own destiny, once one knows what to do. This is only possible by leaving the unipolar system and, above all, its constructs to enter a new multipolar order, so that each state can regain its sovereignty and have its own weight in the contemporary geopolitical framework.

Armando Savini is an economist, essayist, scholar of biblical exegesis and Jewish mysticism. After graduating in Political Science and a master's degree in HR Management, he worked on the science of complexity and its applications to economics. A former lecturer in Economic Policy at Prof. Giovanni Somogyi's chair at the Faculty of Political Science at La Sapienza, he has been an adjunct lecturer in economic history, economics, HR management and research methods for business. He edited Heartland. Il cuore pulsante dell’Eurasia (2022), with the translation of some articles by H. J. Mackinder. His latest publications include: Sovranità, debito e moneta Dal Quantum Financial System al Nuovo Ordine Multipolare (2022, 3rd ed.); Miti, storie e leggende. I misteri della Genesi dal caos a Babele (Diarkos 2020); Le due sindoni (Chirico, 2019); Il Messia nascosto. Profezie bibliche alla luce della tradizione ebraica e cristiana (Cantagalli-Chirico, 2019); Maria di Nazaret dalla Genesi a Fatima (Fontana di Siloe, 2017); Risurrezione. Un viaggio tra fede e scienza (Paoline, 2016); Dall’impresa-macchina all’impresa-persona. Ripensare l’azienda nell’era della complessità (Mondadori, 2009).